Beyond the Hacking Headlines

Divides in Americans’ perceptions of election hacking

Amidst the cacophony of breaking news we live through each week, “election hacking” has become a familiar refrain in US politics. It’s trotted out routinely by wonks and politicians of all stripes in discussions on the 2016 elections; it looms over conversations about the midterms later this year.

But outside the rarified air in politics, what do Americans really think about the issue? Do they think it’s an issue?

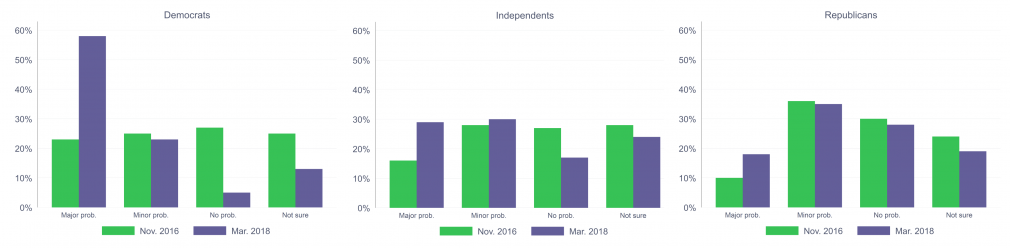

MIT professor and Election Lab founder, Charles Stewart III, took a look at these questions in a recent survey, in which he re-asked some questions about election hacking he had first used right after the 2016 election. In both 2016 and the current survey, respondents were asked how big a problem they thought computer hacking was in the 2016 election. In the newer survey, they were also asked what they thought election hacking was most likely to consist of.

Changing Perceptions

Spoiler alert: Americans don’t agree on an answer for either question. (Go figure.) But it is interesting to see how perceptions overall have changed. Per Stewart:

Back in November 2016, 17% of respondents thought computer hacking in elections was a major problem nationwide… Last week, when I asked identical questions again, the percentage of Americans believing computer hacking in 2016 was a major problem had doubled — to 38%.

Perceptions of whether hacking was a problem in local elections went through a similar jump. Beyond that, however… opinions split. More specifically, they split along partisan lines. (Groundbreaking, you’re right.) Even though Democrats, Republicans, and Independents were all more likely to see computer hacking as a major problem in 2016, Democrat respondents underwent the biggest shift between November 2016 and March 2018:

What implications do these results have for the politics of election hacking — and importantly, the policy response? See the full analysis here.

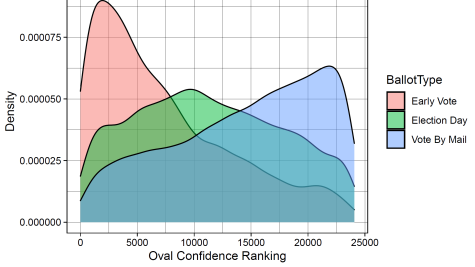

The survey also asked what respondents thought of when they heard the phrase “election hacking.” Was it a foreign actor, lurking in the shadows á la every James Bond movie? Was the threat coming from inside the house, from other Americans? Was it coming in the form of a direct attack on voting machines, or from more nebulous influences on social media?

Once again, respondents didn’t agree on exactly where they think the threat is most likely to come from.

A plurality of respondents –including a majority of those identifying as Democrats — focused on foreign influences, but 20% replied that “nothing in particular” came to mind. Answers were also affected by how closely respondents followed the news. What do these splits mean, and how far can we really read into them?

The short answer is: it’s hard to know exactly what’s going on without a closer look. It’s not as simple as saying “Democrats think there’s a problem and Republicans don’t.” Read on here for the full discussion of the data and what new questions it raises for scholars and public officials to consider.