Measuring Voter Engagement in Election Administration

How Much Do States Expect From Local Election Officials?

The MIT Election Data and Science Lab helps highlight new research and interesting ideas in election science, and is a proud co-sponsor of the Election Sciences, Reform, & Administration Conference (ESRA).

Thessalia Merivaki and Mara Suttman-Lea recently presented a paper at the 2019 ESRA conference entitled, “Measuring Voter Engagement in Election Administration: How Much Do States Ask from Local Election Officials?” Here, they summarize their analysis from that paper.

During the June 2018 primary elections in New York City, many voters showed up to their assigned polling location only to find it closed. Mistakenly believing they had a primary candidate to vote for, it was only after the fact they learned their polling site was not open for primary voting because their Congressional candidate was running uncontested.

Many voters were “infuriated their time was wasted,” and fielded their complaints through Common Cause, a non-profit organization dedicated to supporting American democracy. Susan Lerner, the director of the organization pointed to New York’s lawmakers as a major and consistent source of voter confusion. “New York State does nothing to inform voters,” she noted. “We make it extraordinarily difficult to vote in this state… It’s not surprising that people are completely confused.”

Negative voter experiences rooted in poor information about elections — like the closing of polling places — may not be isolated incidents but rather reflective of broader differences in the information that is made available and advertised to the public about how to vote. There is a wide range of information voters need in order to vote and have their vote counted accurately, including registration deadlines, what documents are needed to register, locations of polling places, the identification needed to vote, and how to actually properly mark a ballot so one’s vote is counted. Challenges in accessing this information ultimately limit the ability of voters to successfully register and cast a valid vote.

Our Research

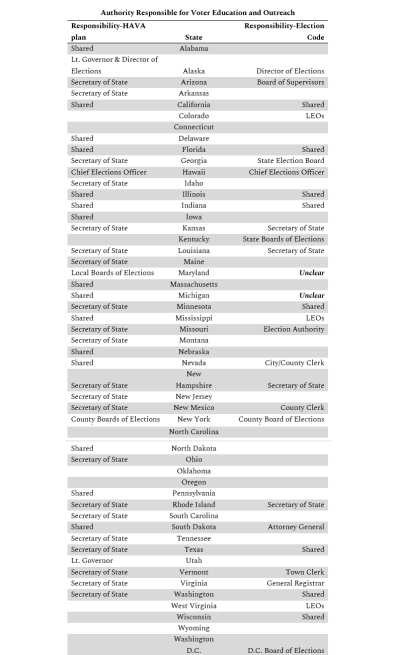

Integral in the efforts to educate and inform voters about changes to election processes are election administrators: the state and local bureaucrats in charge of interpreting and implementing voter education policies to ensure the public is informed about elections. Our research examines what states ask of their state and local election administrators in terms of voter education activities. To do so, we coded voter education plans that were submitted as a part of the federal Help America Vote Act of 2002 (HAVA) and what is actually written in state laws. We were primarily interested in three aspects of these policies. One, we wanted to account for the kinds of activities mentioned. Two, we wanted to assess where responsibility for voter education was delegated; we paid particular attention to whether or not state or local election administrators bore the primary burden of this responsibility. Finally, for state election laws we also examined whether a given state even made mention of voter education and outreach in their election laws (many did not).

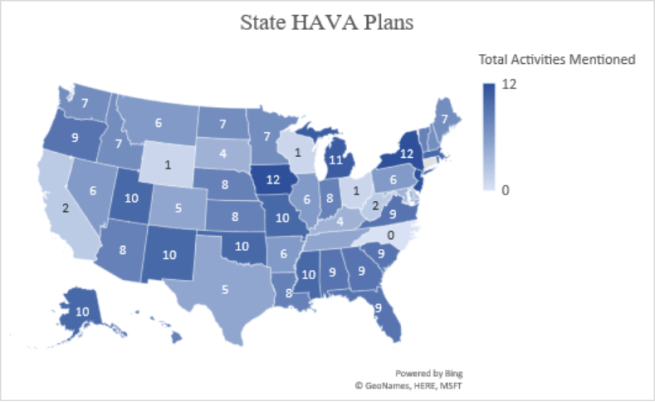

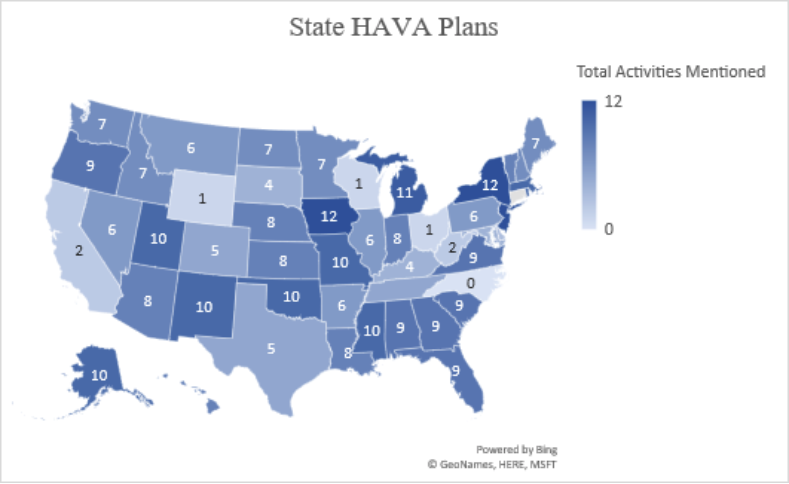

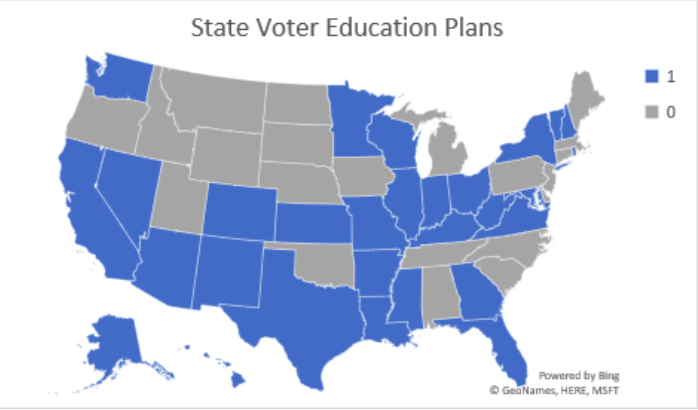

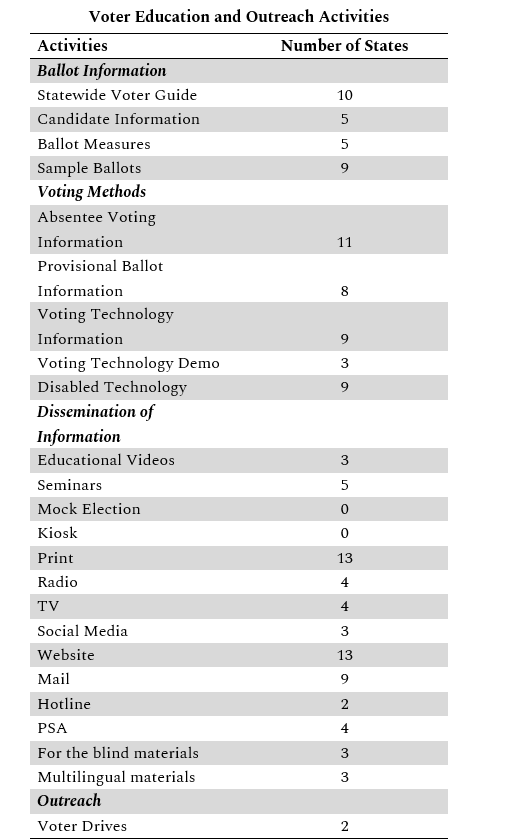

Election administration in the United States is highly decentralized, with most of the authority over how elections are run given to state and local administrators. Not surprisingly, in our examination of state submitted HAVA plans we found substantial variation in the types of activities discussed and who was listed as responsible for voter education. The figure below displays the number of activities listed for each state based on their HAVA plans. A handful of states list at least 10 activities, but the most common of activities mentioned across states is “outreach” (30 states) and distributing election information in print (32). All states’ HAVA plans ultimately did include a voter education section, but not many expanded beyond an ambiguous statement about the importance of voter education in American elections.

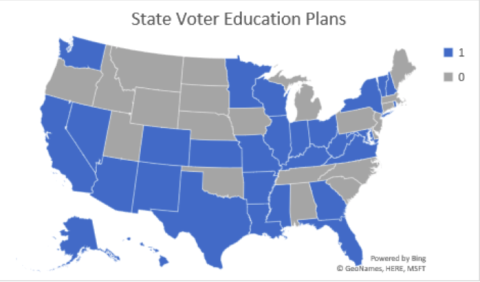

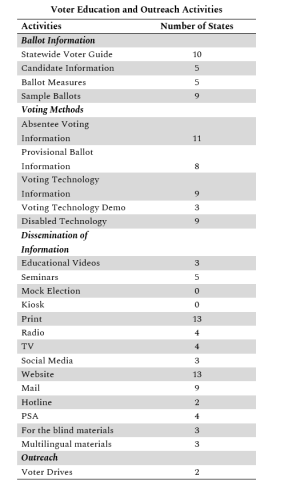

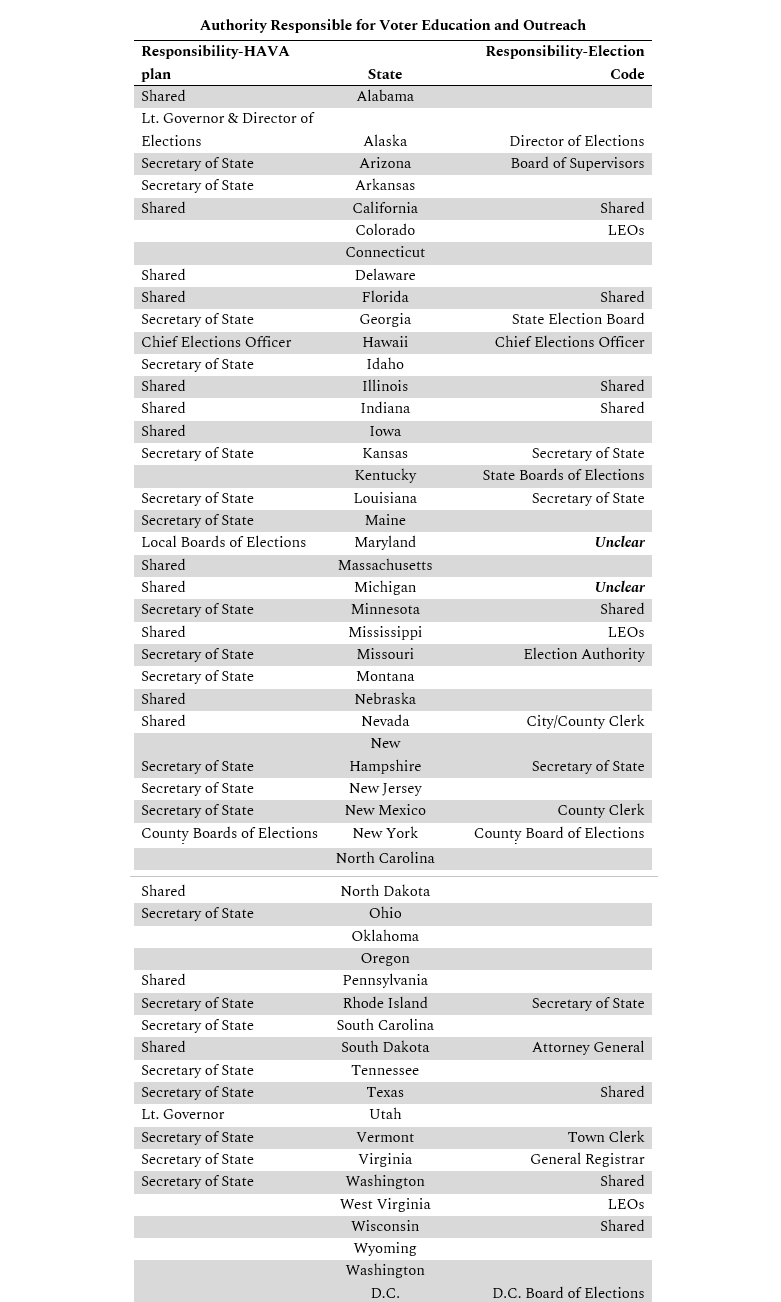

Although all state HAVA plans included at least some mention of voter education, looking at state election laws we found that only 29 states mentioned voter education at all. Moreover, there was a wide range of specificity in the states that did mention voter education. The table below shows the number of activities referenced in the context of specific voter education statutes. Similar to the HAVA submitted plans, the most common activity is using print media to educate voters about elections. Statewide websites were also mentioned as a means to disseminate information. Eleven states explicitly mention voter education in the context of educating voters on absentee voting and eight instruct election officials to inform voters about provisional ballots. Only eight states include voting technology in their voter education statutes, considerably fewer compared to the HAVA plans.

Voter Education Mentions Across the States

Voter Education Mentions Across the States

We also looked at the differences between the responsibilities as outlined in state submitted HAVA plans, and what is written in state election codes in states that discuss voter education. In only four of the thirty states (Kansas, Louisiana, New Hampshire, and Rhode Island) does the Secretary of State remain as the authority on voter education and outreach. In some places like Georgia, Kentucky, and Washington D.C., the creation of statewide election boards who oversee implementation of election laws — including voter education programs — represent organizations states have created since the adoption of HAVA to help administer election. By and large, however, responsibility over education and outreach is unclear, shared, or falls under the jurisdiction of local election officials.

Takeaways

While each state was required to submit a plan for voter education as a part of the Help America Vote Act, not all states detailed voter education plans as a part of their state election codes, and some do not mention voter education at all. This does not mean that states without stipulations for voter education in their election laws have no voter education programs at all. It could be that state legislators and election administrators felt it was not necessary to encode voter education provisions in state statutes. It may also be the case that certain states with strong traditions of highly decentralized election administration where the ins and outs of administering elections — including voter education — are left almost entirely up to localities.

Like most other aspects of United States elections, we found significant differences in the scope of voter education policies across American states. While this research is descriptive in nature, our next steps will be to conduct research that explains some of the differences in state HAVA plans and election laws, examine the effect of state policies on the actual efforts of state and local governments to educate voters and, in turn, consider the impact of these policies on voters themselves.