MEDSL Explains: Voting from Abroad

Americans went to the polls in 1864 to cast their votes for president in the middle of a war — a first for a democracy. Union soldiers also enjoyed another first: despite being absent from their hometowns on Election Day, many of them were able to use new processes to participate and vote from afar.

Throughout the rest of the nineteenth and most of the twentieth centuries, the laws governing who was able to vote in a time or place other than their specific polling location on Election Day varied from state to state and election to election. In the last few decades, though, efforts have increased to include members of the military (as well as other citizens who live abroad or are otherwise unable to show up in person to vote) in elections. Now, federal and state laws have allowed voting from abroad to become a unique but important aspect of U.S. elections.

Legal basis

The legal foundations for voting from abroad rest primarily on the Uniformed and Overseas Citizens Voting Act (UOCAVA), which was passed by Congress in 1986. Under this law, eligible members of the military, other government agencies, and civilians permanently living abroad are able to use a legal mechanism for absentee voting, which is administered by the Federal Voting Assistance Program (FVAP). That agency, in turn, sits within the Department of Defense (DOD). Although FVAP provides services for all voters abroad, the fact that it is ultimately administered by the DOD highlights the military aspect of the population that UOCAVA covers.

In 2009, Congress passed the Military and Overseas Voter Empowerment (MOVE) Act to provide more support to UOCAVA voters. The law requires that states accept electronic voter registration for potential UOCAVA voters, as well as mandating that military installations have voting assistance offices. In addition, the MOVE Act also requires that states send ballots to UOCAVA voters well in advance — at least 45 days before an election.

Along with UOCAVA and MOVE, some parts of the National Voting Rights (NVRA) and Help America Vote (HAVA) Acts also apply to overseas or military voters who might need to vote from abroad. Under the NVRA, the DOD is required to implement voter registration procedures not unlike those used by ordinary citizens at state motor vehicle bureaus. After HAVA passed, the DOD was also required to take on other tasks not unlike the responsibilities states have: providing information to voters about deadlines and registration processes. HAVA straightened out some tangles in UOCAVA implementation as well, mandating a uniform application of the law’s requirements across all states.

Who are UOCAVA voters?

Defining the groups that make up the UOCAVA population can be difficult. For starters, not all UOCAVA voters register or vote using the provisions of the law that were specifically tailored for them. Technically, the 1986 law applies to:

- all active duty members of the military,

- members of the Merchant Marine,

- the commissioned corps of the Public Health Service and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration,

- family members of these groups,

- and regular civilians residing abroad.

However, if UOCAVA voters use traditional methods to register and vote — which many do — they’re counted among the general voting population instead. As a result, they aren’t captured by any administrative assessments aimed specifically at measuring the UOCAVA population.

Speaking more broadly, the UOCAVA population can be segmented into its two largest sub-populations: the active duty military and civilians living abroad. Even with this broader scope, it is surprisingly difficult to estimate how many people are covered under UOCAVA, especially when it comes to civilians living abroad. Recent research suggests that altogether, there are about 3.9 million eligible UOCAVA voters, with overseas civilians making up 2.6 million of that total. This creates a voting-eligible population comparable to that of Colorado. (Seen in that light, perhaps it is unsurprising that the difficulty in quantifying the population more specifically can be frustrating to election officials and scholars alike.)

Registration and voting

Like any other U.S. voter, UOCAVA voters must be registered to vote in a specific state or territory. Unlike ordinary citizens, however, they’re able to use registration methods that aren’t broadly available. UOCAVA voters can use the Federal Post Card Application (FPCA) to register to vote, request ballots, and update their contact information with their local election office from afar.

Once they register, there are a few ways that UOCAVA voters can cast their ballots. Military voters that still live in their state of residence and are near their polling location can vote in person just like any other registered voter, or can choose to send in a regular absentee ballot (pursuant to the laws of the state in which they’re registered, of course).

Where that isn’t possible, UOCAVA voters can take advantage of specific mechanisms that states have in place for receiving their ballot requests and transmitting the ballots in turn. FVAP actually provides an online tool to help facilitate the process for all states and eligible territories.

UOCAVA voters also have another mechanism they can use to vote: the Federal Write-in Ballot (FWAB). The FWAB, much like the FPCA, serves as a backup mechanism for UOCAVA voters. Instead of using a more standardized absentee ballot, UOCAVA voters can use the FWAB form to vote by write-in (although certain restrictions still apply, and vary by state).

Trends in UOCAVA voting

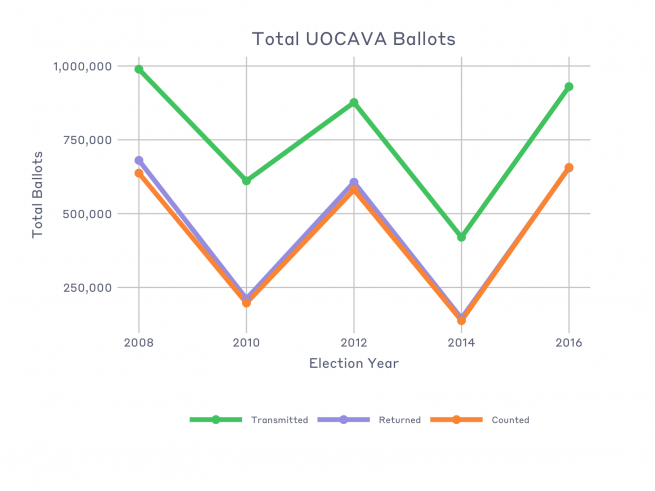

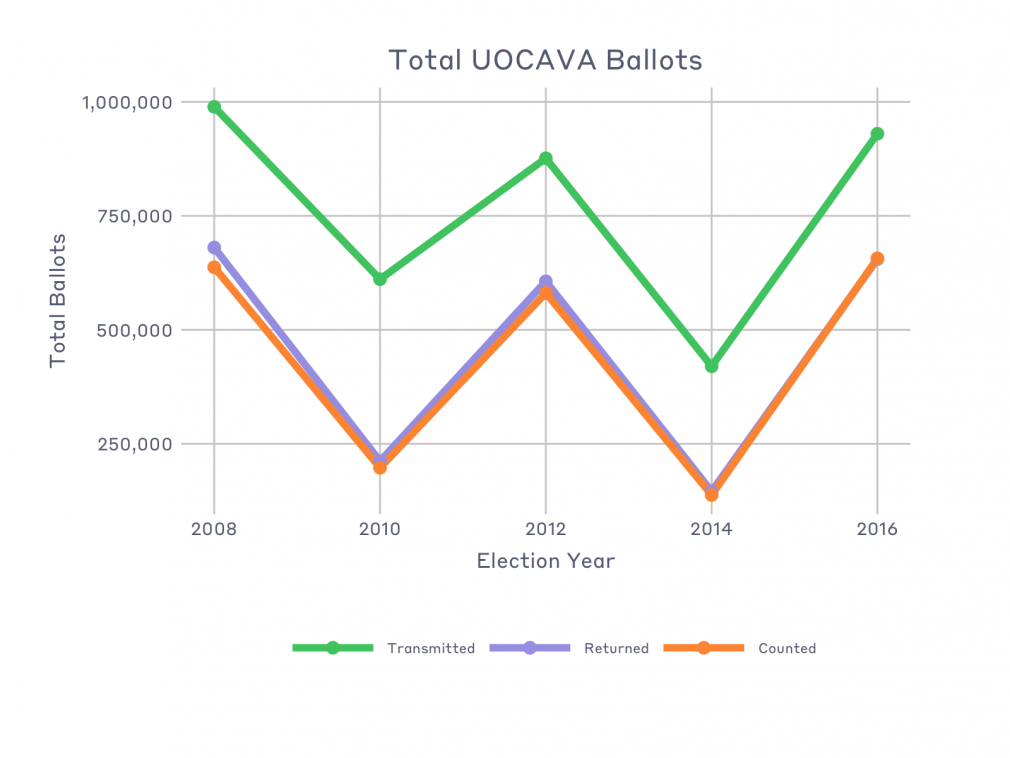

With all these processes and mechanisms, how can states (or scholars) track whether and how UOCAVA voters actually vote? Primarily, using data from the Election Administration and Voting Survey, which is conducted by the Election Assistance Commission (EAC). Not all states report their data to the EAC, but even so, it’s possible to see a few trends from recent years. Perhaps the most important of these is the reduced number of rejected ballots, as the ratio of ballots returned and counted in recent elections has reached relative parity.

Overall, voter turnout among overseas civilians is quite low. Estimates suggest that over the past few elections less than 6% of this population voted, although the number of voters was up in 2016. Are changes in these voting rates due to politics, or problems in administration? That much is unclear, but as we can see in the graph above, administrative issues have diminished in recent years.

FVAP is required to report to Congress on the effectiveness of the program (you can read the most recent post-election version here), an effort that includes a series of post-election surveys that ask members of the military about their registration and voting histories.

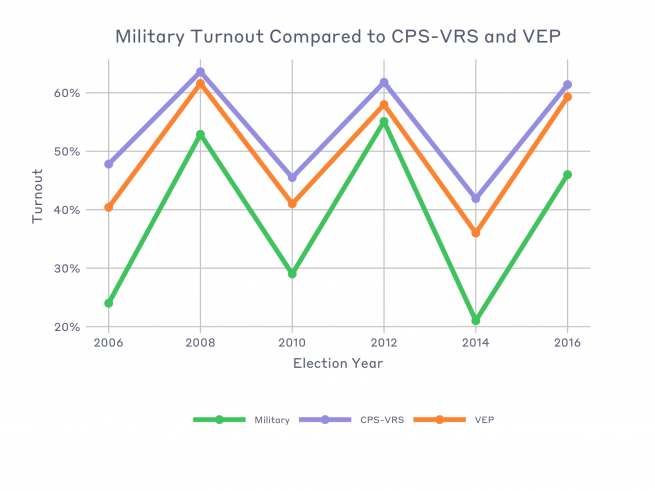

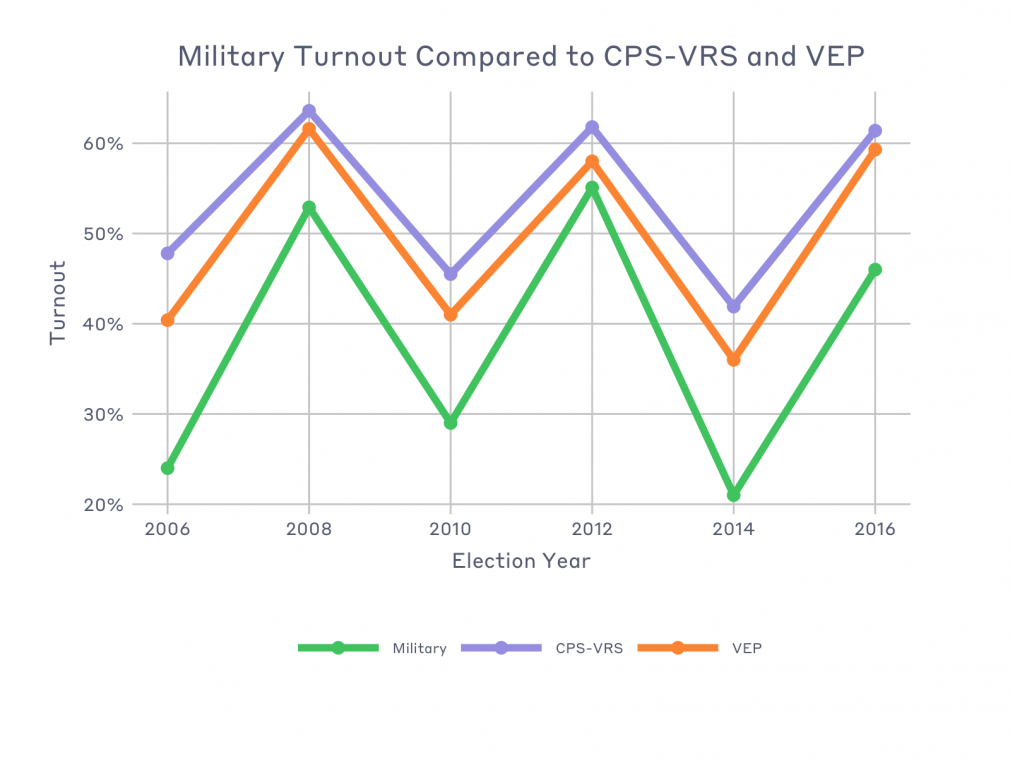

According to the survey, self-reported voter turnout among the military has generally been comparable to that of the general civilian population, although in 2016 the rate fell to about 46%. This is around 13% less than was reported in 2012, and lower (by about the same amount) than the rate for the general population in 2016. It’s not clear how much the traditional problems associated with self-reported voting also apply to the military, but there’s not much reason to think they aren’t equally applicable. Below, we’ve mapped out the turnout level for the active-duty military (as computed by FVAP Reports), compared with self-reported turnout (on the Current Population Study’s Voting and Registration Supplement (CPS-VRS)) and voting-eligible population (VEP) turnout (as calculated by the United States Elections Project):

Politically, UOCAVA citizens are just as varied in their attitudes and preferences as any other segment of the broader voting population. There is some research suggesting that enlisted members of military are less likely to be strong partisans than their civilian counterparts, while officers tend to lean more Republican than Democrat. It should be noted, however, that political studies of the military population are rare, and should be taken with the caveat that this group is difficult to sample and mostly shielded from traditional survey efforts. Representative data on overseas civilians is even rarer, although qualitative assessments suggest this population tends to prefer Democratic candidates.