MEDSL Explains: Voting by Mail and Absentee Voting

Traditionally, Americans have voted in person at neighborhood polling places. Beginning in the 1980s, though, many states began to ease rules on how and when absentee ballots were issued — thus allowing voters to cast ballots in person before Election Day — or even mailing ballots directly to all voters.

Introduction

Absentee voting and voting by mail have typically been viewed as synonymous in the United States because absentee ballots were historically distributed by mail to voters temporarily away from their homes, and in general no one else was allowed to use this particular way of voting. For this reason, we’ll consider both topics together in this post.

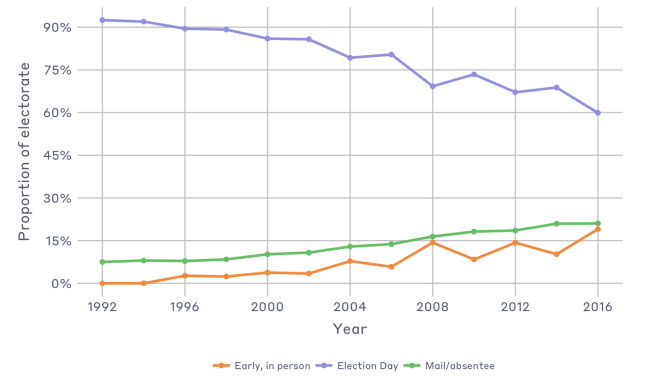

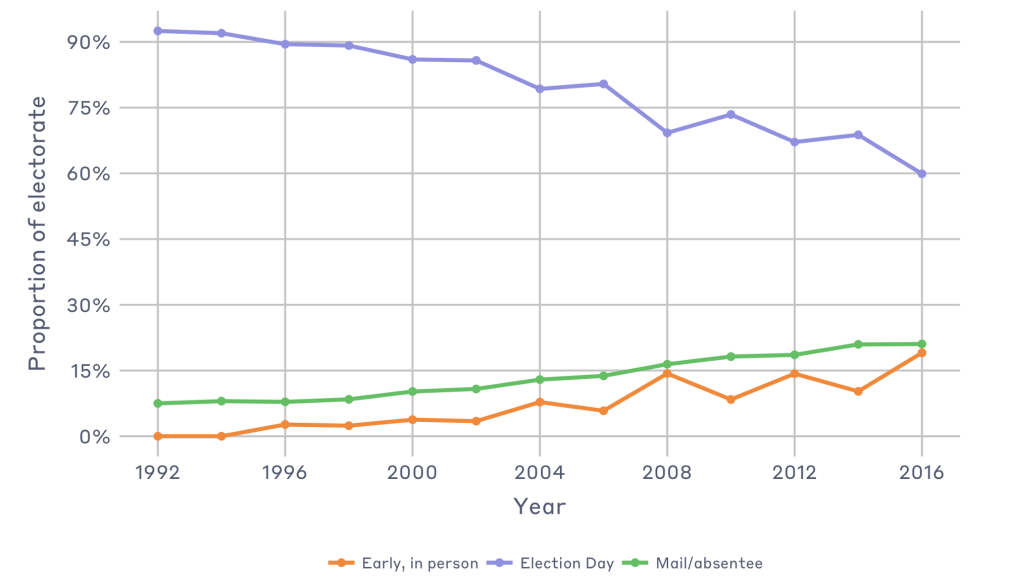

In the graph below, we can see the percentage of voters (since 1992) who cast their ballots through the three major modes of voting: in person on Election Day, in person before Election Day, and by mail/absentee ballot:

These statistics are based on self-reports by respondents to the Voting and Registration Supplement of the Current Population Survey (CPS).

These statistics are based on self-reports by respondents to the Voting and Registration Supplement of the Current Population Survey (CPS).

The rise in voting by mail (VBM) raises a number of important academic and policy issues. Do more flexible vote-by-mail policies increase turnout? Does an increased rate of voting by mail decrease civic engagement, or decrease the impact of an “October surprise?” — that is, an event at the end of a political campaign intended to affect the outcome?

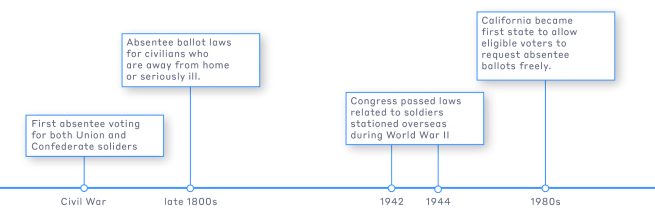

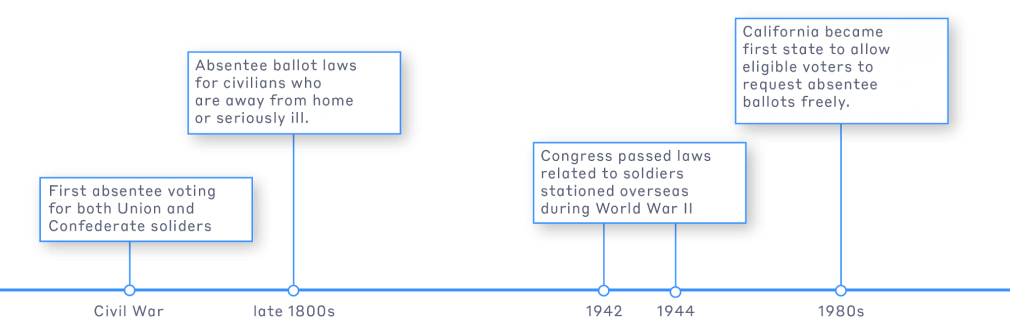

History and expansion

The idea that ballots could be cast anywhere other than a physical precinct close to a voter’s home hasn’t always been embraced in the United States (and still isn’t in many other countries). What we in the U.S. now call absentee voting first arose during the Civil War, when both Union and Confederate soldiers were given the opportunity to cast ballots from their battlefield units and have them be counted back home.

The issue of absentee voting next became a major issue during World War II, when Congress passed laws in 1942 and 1944 related to soldiers stationed overseas. Both laws became embroiled in controversies over states’ rights and the voting rights of African Americans in southern states, so their effectiveness was muted. Subsequent laws, particularly the Uniformed and Overseas Citizens Absentee Voting Act (UOCAVA) and the Military and Overseas Voter Empowerment (MOVE) Act, have been more effective in encouraging voting by service members through absentee voting.

States began passing absentee ballot laws for civilians in the late 1800s. The first laws were intended to accommodate voters who were away from home or seriously ill on Election Day. The number of absentee ballots distributed was relatively small, and the administrative apparatus that developed to support the effort was never designed to distribute a significant number of absentee voters.

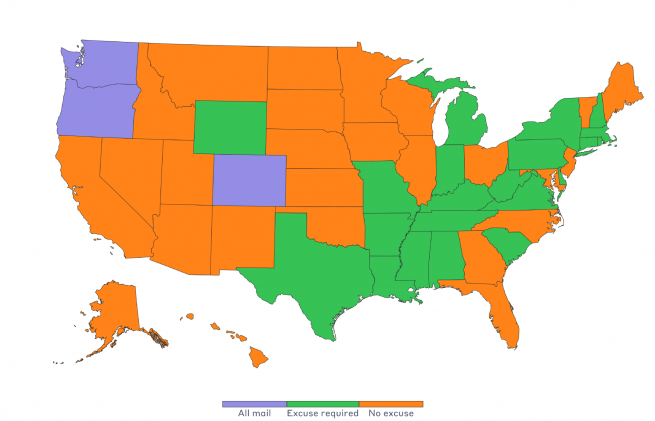

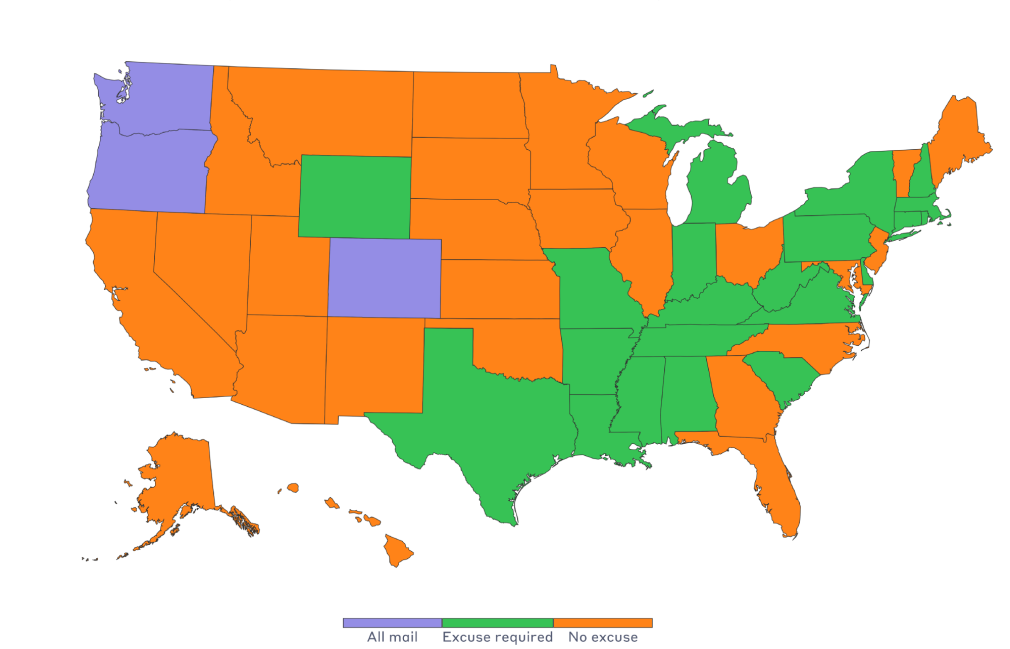

In the 1980s, California became the first state to allow eligible voters to request absentee ballots for any reason at all , including their own convenience — appropriately labeled a “no-excuse” absentee ballot. The idea caught on; by 2016, 27 states had adopted no-excuse absentee laws. The map below classifies states according to their absentee/mail ballot regimes. According to respondents to the 2016 CPS, 29% of voters in no-excuse states cast their ballots by mail, compared to 9% in states that still required an excuse.

Absentee/Mail ballot regimes in the U.S. (Source: National Conference of State Legislatures)

Since California began implementing no-excuse absentee voting, ten states have taken the next step and allowed all residents to request an absentee ballot for every election. These “permanent absentee” states now have even greater use of absentee ballots. In 2016, 42% of voters in states that had permanent absentee laws voted with an absentee ballot.

VBM: the Oregon system

In a referendum that passed in 1998, Oregon went even further by agreeing to issue all its ballots by mail. Washington followed suit in 2011, and Colorado in 2013.

It’s important to note that although Colorado, Oregon, and Washington now distribute all their ballots by mail, voters do not return them all by mail. According to responses to the 2016 Survey of the Performance of American Elections, 73% of voters in Colorado, 59% in Oregon and 65% in Washington returned their ballots to some physical location such as a drop box or local election office. Even among those who returned their ballots by mail in these states, 47% dropped off their ballot at a U.S. Post Office or neighborhood mailbox rather than having their own postal worker pick it up at home. Thus, it’s more accurate to describe these states as “distribute ballots by mail” states.

Administrative issues

The expanding opportunities to cast an absentee ballot or to vote by mail have not been uncontroversial. Perhaps the most important issue has been whether expanding VBM opportunities increases voter turnout. Facilitating VBM presumably reduces the costs of voting for most citizens, so it’s reasonable that we would expect it to increase turnout.

The scientific literature on this empirical question about turnout has been mixed, though. An early study of the effects of VBM on turnout in Oregon argued that its implementation had caused turnout to increase by 10%. However, subsequent research has had difficulty replicating these initial findings. The safest conclusion to draw is that extending VBM options increases turnout modestly in midterm and presidential elections but may increase turnout more in primaries, local elections, and special elections. This modest increase likely comes in two ways:

- by bringing marginal voters into the electorate, and

- by retaining voters who might otherwise drop out of the electorate.

Another question surrounding VBM is whether it increases voter fraud. There are two major features of VBM that raise these concerns. First, the ballot is cast outside the public eye, so the opportunities for coercion and voter impersonation are greater. Second, the transmission path for VBM ballots is not as secure as traditional in-person ballots. These concerns relate both to ballots being intercepted and ballots being requested without the voter’s permission.

As with all forms of voter fraud, documented instances of fraud related to VBM are rare. However, even many scholars who argue that fraud is generally rare agree that fraud with VBM voting seems to be more frequent than with in-person voting. (For the curious: two of the best-known cases of voter fraud involving absentee voting occurred in 1997 in Georgia and Miami.)

Finally, skeptics of convenience voting methods such as VBM argue that they encourage voters to cast their ballots before all the information from the campaign is revealed, thus putting early voters at a civic disadvantage. In response, it can be argued that as more voters cast early ballots by mail or in person, campaigns have less incentive to hold onto negative information about their opponents in the hope of gaining an advantage through an October surprise. Empirically, it’s important to note that the earliest voters tend to be the strongest partisans, and thus are less likely to be swayed by last-minute information.