Voting by Mail During a Global Pandemic

America’s Electorate is Increasingly Polarized Along Partisan Lines About Voting by Mail During the COVID-19 Crisis

This post presents findings published by Mackenzie Lockhart, Seth Hill, Jennifer Merolla, Mindy Romero, and Thad Kousser. The full paper, “Are Voters Polarized Along Party Lines About How to Run Elections During the COVID-19 Crisis?” was presented at the 2020 Election Science, Reform, and Administration Conference.

Facing the threat of the COVID-19 crisis, elected officials from the major parties have offered sharply divergent prescriptions about how to run November’s election.

Democratic Senators Amy Klobuchar and Ron Wyden have introduced legislation to expand access to voting through the mail and some states have proposed to run their primaries entirely through the mail (1). In California, Democrats have passed a new law to send vote-by-mail ballots to every active Californian voter (2). Republican leaders have spoken against the mandatory mail ballot approach (3); among President Trump’s many tweets on the subject, he has said that “Republicans should fight very hard when it comes to state-wide mail-in voting. Democrats are clamoring for it. Tremendous potential for voter fraud, and for whatever reason, doesn’t work out well for Republicans.” (4)

Prior research has shown little party divide on voting by mail, with nearly equal percentages of voters in both parties choosing to vote this way in past studies (5, 6, 7). When counties adopt universal vote-by-mail, for example, the partisan composition of the electorate does not change. Instead, the main effect is to increase turnout across all groups (5). Similarly, when mandatory vote-by-mail has been introduced there has been no measurable effect on election outcomes (7). Clearly in the past, vote-by-mail has not resulted in partisan biases.

We asked how the public views vote-by-mail policies in light of the COVID-19 pandemic and growing polarization among elites. Has a divide opened up this year in how voters aligned with the Democratic and Republican parties want to cast a ballot? If so, policies that expand access to vote by mail could have partisan effects, as President Trump and others have claimed. If not, they will likely bring little shift in composition of electorate.

To answer these questions, we conducted two nationally diverse online surveys of eligible voters in April and June of 2020 with 5,612 and 5,818 respondents respectively. The surveys were fielded with using Lucid’s Fulcrum platform (http://luc.id). This platform has previously been demonstrated to provide nationally diverse samples that exhibit similar treatment effects to samples from other sources (8). We weighted our responses so that they reflected the national, voting age population. Embedded in this survey was an experiment; respondents were randomly assigned to receive no additional information, information from scientists predicting a spring peak in COVID-19 cases, or information from scientists predicting a fall peak in COVID-19 cases.

How did voters feel at the start of the pandemic?

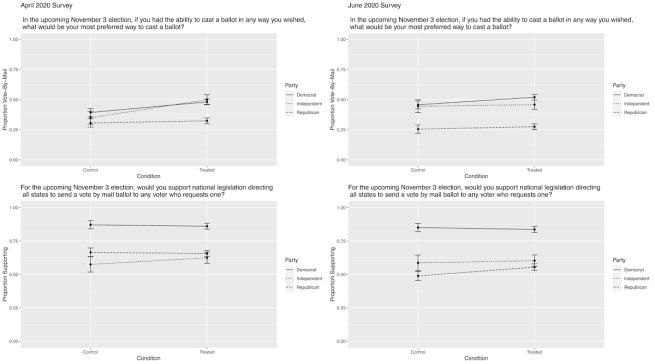

The graphs in the left in Figure 1 show how Americans viewed vote-by-mail in April. When Americans were still adjusting to life during the COVID-19 pandemic, they already had broadly favorable views towards vote-by-mail. Without being presented with any additional information about the COVID-19 pandemic; 87% of Democrats and 64% of Republicans supported national legislation that would expand no-excuse absentee balloting across the country. We also found broad support for other vote-by-mail policies; a majority of eligible voters also supported automatically distributing vote-by-mail ballots (63.9%), allowing ballots to be postmarked on election day (73.9%), and even switching to an exclusively vote-by-mail system (56.9%). Our treatment had relatively little effect on these support levels, possibly because the baseline level of support was so high.

In terms of personal preferences of how voters want to cast their own ballots, we found that there was a significant gap between partisans, especially once we exposed them to scientific projections. Without being presented with a scientific projection about COVID-19, there was a 10 percentage point difference between partisans on whether they would like to vote by mail; 40.1% of Democrats indicated their preference was to vote by mail while only 30.5% of Republicans wanted to do so. To us, this suggested that in April there was some polarization on the issue, but broadly Americans had high levels of support for expanding vote-by-mail options.

What changed?

When we surveyed a new wave of Americans in June, we found that things had changed significantly. Between April and June, there was a prominent national discourse surrounding vote-by-mail; President Trump and prominent Republicans repeatedly argued that vote-by-mail was susceptible to voter fraud while Democrats pointed to past evidence suggesting that voter fraud was uncommon in states with vote-by-mail. There was also a growing divide on how partisans viewed the pandemic; Republicans increasingly believed the pandemic’s economic effects to be outweighing the public health effects and called for more reopening of the American economy.

Our respondents seem to have followed these trends in elite discourse, as evidenced by the differences between respondent patterns in April and June in Figure 1. By June, Republicans had become significantly less supportive of national vote-by-mail legislation than Democrats; Democrats dropped a small amount (2.3%) but Republican support dropped a whole 12.6%, dramatically increasing the gap between parties.

Respondents’ own preferences over how to cast a ballot was also polarized. While in April there was a small 10% gap between parties; in June, this gap had become 20% with more Democrats hoping to vote by mail while fewer Republicans preferred this option. Almost half of all Democratic respondents (44.8%) said that they intended to vote by mail in November, while only 25.5% of Republicans felt the same way. This shows that a large increase in the polarization over voting by mail occurred from April to June, in line with the increasingly polarized elite debate and increasingly polarized views of the pandemic.

Implications going forward

One challenge of studying vote-by-mail intentions during a pandemic is that it can be hard to project forward what current data means. We can’t say, for instance, that a partisan divide in trust for vote-by-mail means that the electorate in states with vote-by-mail in place will have a different partisan composition than those in states without vote-by-mail. For many voters, voting by mail and voting in person are likely substitutes for one another — if in person options are risky, they would vote by mail and if voting by mail options are limited, they’ll vote in person.

However, while the paper doesn’t speculate much about the consequences of this polarization, I do think there are a few reasons that policy makers and researchers should pay attention to both the growing divide in support for policies that would expand vote-by-mail and in how Americans want to cast their own ballots. One of these reasons is that, during this pandemic, voting has faced new and unique challenges. There have been numerous examples in which voting in person has faced challenges like limited polling places and uncertain social distancing procedures (9, 10, 11). The pandemic has made it difficult for election administrators to find the necessary space to offer safe, socially distanced, in-person voting options. The result of this has been longer lines and stress for voters who are concerned about their own health. As the modality of voting seems to have become more polarized, this might mean that the impact of long lines and limited polling places will have a partisan effect, making it more difficult for Republican voters to vote.

Voting by mail has also seen logistical issues that might become increasingly important as voting modality has polarized. Recently, the United States Postal Service has become concerned with the potential for ballots to be delivered late because it lacks the capacity to deal with additional mail in the coming months. This could cause problems if there are disruptions in mail services that cause ballots to arrive late, whatever the cause might be.

With the backdrop of a global pandemic, it is hard to know exactly how the gap in how Democrats and Republicans will want to vote will play out in November. A second wave of COVID-19 in the fall might disrupt in-person voting, mail service, or both, which would have strong effects if Democrats and Republicans really do vote in different ways.

I also believe that the policy implications themselves are important. Legislators across the country should note the generally high levels of support for vote-by-mail policies that we observed. Even with the polarization we observe, in June a majority of people in both parties supported expanding no-excuse absentee ballots nationwide. Voters across the political spectrum support an increase in the availability of voting options. Legislators might benefit from taking advantage of this issue that has broad support and invest in making voting more accessible.

Work CIted

- J. Bowden, “Klobuchar, Wyden call for expanded mail-in and early voting amid coronavirus outbreak.” The Hill March 16, 2020.

- A. Koseff & J. Wildermuth, “Gov. Gavin Newsom signs bill sending mail ballot to every active California voter.” San Francisco Chronicle June 18, 2020.

- J. Rutenberg, M. Haberman, N. Corasaniti, “Why Republicans Are So Afraid of Vote-by-Mail.” The New York Times April 8, 2020.

- D. Trump. Tweet. April 8, 2020. Available at https://twitter.com/realdonaldtrump/status/1247861952736526336

- D. Thompson, J. Wu, J, Yodder, A. B. Hall, The Neutral Partisan Effects of Vote-by-Mail: Evidence from County-Level Roll-Outs. PNAS.

- A. Berinsky, N. Burns, M. Traugott, Who Votes by Mail?: A Dynamic Model of the Individual-Level Consequences of Voting-by-Mail Systems. Public Opinion Quarterly 65, 178–197 (2001).

- Barber & Holbein (2020) The Participatory and Partisan Impacts of Mandatory Vote-by-Mail, Science Advances.

- A. Coppock, O. A. McClellan, Validating the Demographic, Political, Psychological, and Experimental Results Obtained from a New Source of Online Survey Respondents. Research & Politics 6:1 (2019).

- E. Cox, “Policy change lets Maryland elections officials use ‘voting centers’ instead of polling places.” The Washington Post August 10, 2020.

- R. DeBrock, “Macoupin may consolidate polling places in November.” The Telegraph August 25, 2020.

- Editorial Board, “If you can’t vote by mail, here’s how you can safely do it.” The Washington Post August 16, 2020.