What Happens When the President Calls You An Enemy of the People

Election Officials and Public Sentiment

Since the 2020 election and the rise of the Big Lie, election officials across the nation have been under threat. The people who run American elections are traditionally low-profile officials, but in recent years they have been singled out for abuse on a national scale. In my new working paper co-authored with Samuel Baltz and Charles Stewart III, titled “ What happens when the president calls you an enemy of the people: Election officials and public sentiment”, we focus on finding patterns of threats against election officials and independently documenting them. In doing so, we aim to show when these threats are most prominent, whether they have been getting worse over time, and who is driving them.

Perhaps the most salient example of these threats occurred when Trump directed his Twitter followers at Georgia Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger. He accused Raffensperger of refusing to find “11,780 votes,” the amount which Trump would have needed to become the presumptive winner in Georgia. After this public target was placed on him, Raffensperger received attacks in person and online.

This case illustrates a widespread phenomenon; while Raffensperger is the most extreme case, he is not the only election official experiencing this level of vitriol online and in person. In fact, a nationwide survey of local election officials, conducted earlier this year by Reuters, reported that election officials across the country were concerned with harassment on social media, and documented the threats they were receiving.

Our paper adds on to Reuters’s work and that of others by documenting what drives these violent and often criminal threats: a barrage of rhetoric that is not necessarily violent, but negative and pervasive.

About our Research

Our paper lays out three important elements from our research:

- First, a theoretical contribution to the existing literature on this topic. Previous studies focused on social media have identified a connection between salience and negativity; the more relevant and high-profile a conversation is, the more negative comments crop up. Because election officials in the US became salient very suddenly, we can measure how much that salience provokes negativity.

- Second, and perhaps more practically, we document that the negative rhetoric election officials are targeted with goes far beyond the most extreme threats; they are experiencing a barrage of everyday negative rhetoric.

- Third and finally, our paper looks at the ideologies of people replying to election officials. We demonstrate that the surge of negativity has come toward election officials from both the right and the left ends of the political spectrum. In most cases, we find that conservative secretaries of state attract negative replies from liberal users and positive replies from conservative users, and vice versa. In some extreme cases, however, they can receive negative replies from individuals across the full ideological spectrum.

In order to conduct our analysis, we first collected the entire universe of tweets and replies to tweets from accounts associated with current US secretaries of state or state election offices. Next, we examined the nature of the replies to those accounts. To analyze those replies, we looked at the sentiment of the replies, the words used, and which election accounts were targeted with the most negativity, as well as when those spikes happened. Along with that analysis, we looked closely at who was producing the most negativity, by estimating the ideologies of the users who responded to election officials’ or offices’ accounts. Finally, we compared the rhetoric directed towards American elected officials who are not election administrators, and election administrators who are not American. This provided a necessary point of comparison to understand the scope of the issue at hand.

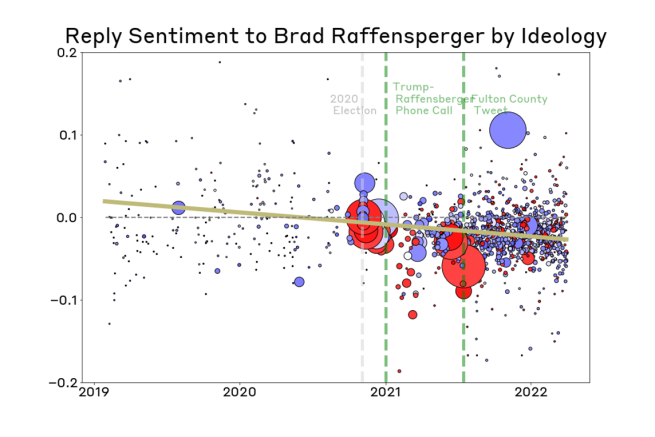

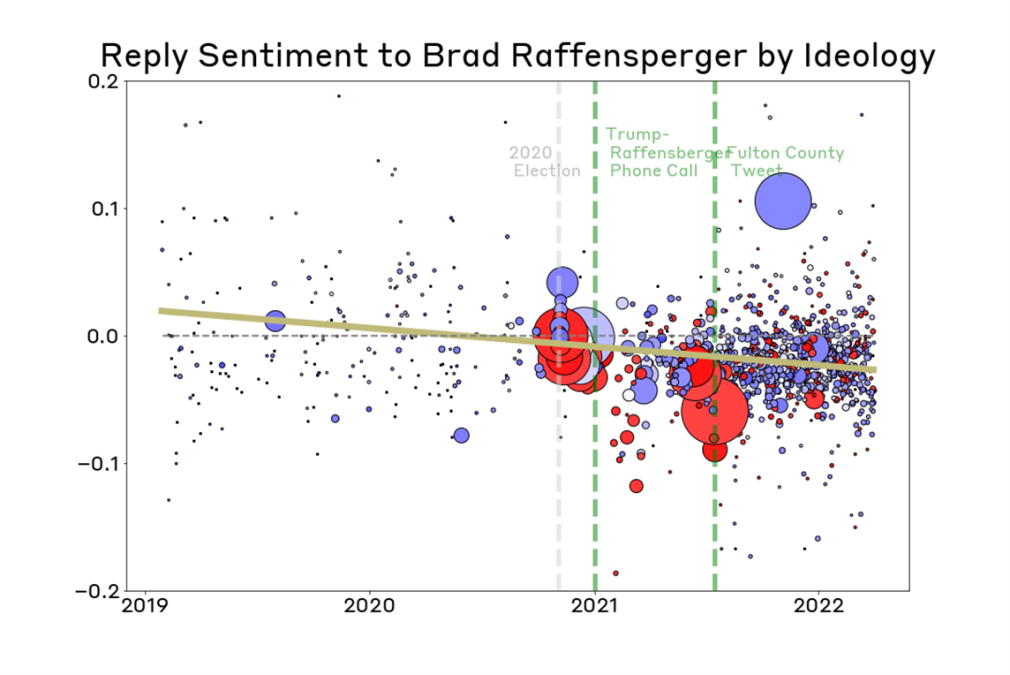

What did we find? Below, we’ve included an example of our findings. This plot shows the average sentiment of tweets that were sent as replies to posts from Georgia’s Secretary of State, Brad Raffensperger, between 2019 to 2022. We’ve highlighted key events, such as the election or Trump-Raffensperger phone call. The points on the plot represent the sentiment of the replies; the size of those points indicates the number of replies to each given tweet; and the color of the point represents the repliers’ average ideologies. Before 2020, Raffensperger’s account drew little attention, and any negative replies stemmed from left-leaning users. After the election and the infamous phone call, however, conservative users made up a much larger portion of the negativity directed at his account.

Raffensperger’s tweet with the largest number of replies is from July 2021, where he criticized the electoral leadership of Fulton County Georgia. This tweet received negative replies from both conservative and liberal users – liberals’ negative replies were likely provoked by the concern that Raffensperger was buying into claims of electoral fraud, while conservatives were likely focused on the perception that he had gone against the party line and had already been deemed a “traitor.”

Our research has allowed us to substantiate and quantify the claims made by election officials across the nation, who have cited a significant uptick in negativity on social media. While the public salience of an official is a major determinant of the threats they receive, officials at all levels of authority, across state and national boundaries, are experiencing negativity directed at them. We find evidence of both liberal and conservative users making these negative tweets; most often they are targeting officials of the opposite party, but in extreme cases we do see people directing their negativity at officials who share their ideology. Election officials are leaving their jobs en masse which leaves democracy in grave peril. We have documented sustained negative rhetoric against those very people; rhetoric that is getting far worse over time.

To read more about our findings, check out the full paper here