Who Votes Without Identification?

Using Affidavits from Michigan to Learn About the Potential Impact of Strict Photo Voter Identification Laws

The MIT Election Data and Science Lab helps highlight new research and interesting ideas in election science, and is a proud co-sponsor of the Election Sciences, Reform, & Administration Conference (ESRA).

Phoebe Henniger, Marc Meredith, and Michael Morse recently presented a paper at the 2018 ESRA conference entitled, “Who Votes without Identification? Using Affidavits from Michigan to Learn about the Potential Impact of Strict Photo Identification Laws.” Here, they summarize their analysis from that paper.

A decade after the Supreme Court upheld Indiana’s first-in-the-nation strict photo voter ID law, the number of citizens prevented from voting by laws like it is still unknown.

This is because it is difficult to measure, at the individual level, who both lacks access to ID and has a desire to vote. A survey can measure both quantities, but it is also most likely to miss those who are least likely to have ID; in addition, surveys are vulnerable to people misreporting their ID status and over-reporting an intention or history of voting.

Alternatively, administrative data can be used to measure who owns a driver’s license as well as who votes. But comprehensive data on who possesses photo identification is often lacking, and missing fields, inconsistent data fields, and typographical errors can make it challenging to link the same individual’s records between different databases. Moreover, even comprehensive data on who possesses photo identification does not contain information about whether they might be unable to access that ID on Election Day. Such people could form a substantial portion of those burdened by a strict voter ID law.

Our Research

We attempt to solve this measurement problem by leveraging novel administrative data on who shows up to vote without photo identification. Previous work has used provisional ballots filed in strict photo ID states to identify individuals who intend to vote but lack ID. Such data, however, cannot capture individuals who intend to vote, lack ID, and — for that very reason — are deterred from showing up at the polls. Our alternative measurement strategy makes use of the distinction between the “strict” states that require identification in order to vote, and the “non-strict” states that merely request it. We collect local administrative records on who does not present ID in a non-strict voter ID state, where people without an ID should not be deterred from voting by the law. These data allow us to put an upper bound on the share of voters who could be disenfranchised if a state shifted from a non-strict to strict photo identification law.

Since 2007, Michigan voters have been asked, but not required, to show photo ID in order to vote. Those who do not have photo ID with them at the polling place sign an affidavit in the presence of an election inspector and then cast a ballot just like any other voter. Importantly, these affidavits are public records subject to the state’s freedom of information law. We collected copies of the affidavits filed in a random sample of 20 percent of Michigan precincts and matched more than 4,000 affidavits to the statewide voter file, allowing us to identify the voters who potentially are at risk of being disenfranchised if the state shifted from a non-strict to strict voter ID law.

Relatively few voters lacked a photo ID while voting in Michigan in 2016. Our baseline estimate is that about 0.6 percent, or about 28,000 voters, would have signed an affidavit had it been required for both polling place and absentee ballots (in practice, absentee voters do not need to file an affidavit). One surprising finding is that the election inspector signs slightly fewer than half of these affidavits. In such cases we don’t know whether the election inspector didn’t follow the proper protocol or voters who possessed ID filled out these affidavits unnecessarily. Thus, we only can conclude that the actual share of voters who lack photo ID is somewhere between 0.2 and 0.6 percent.

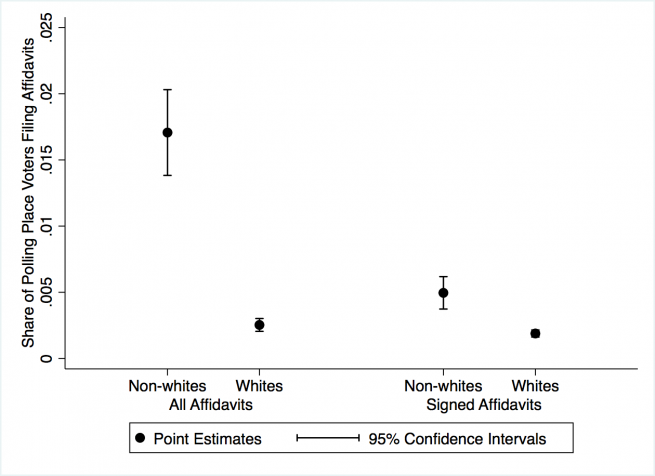

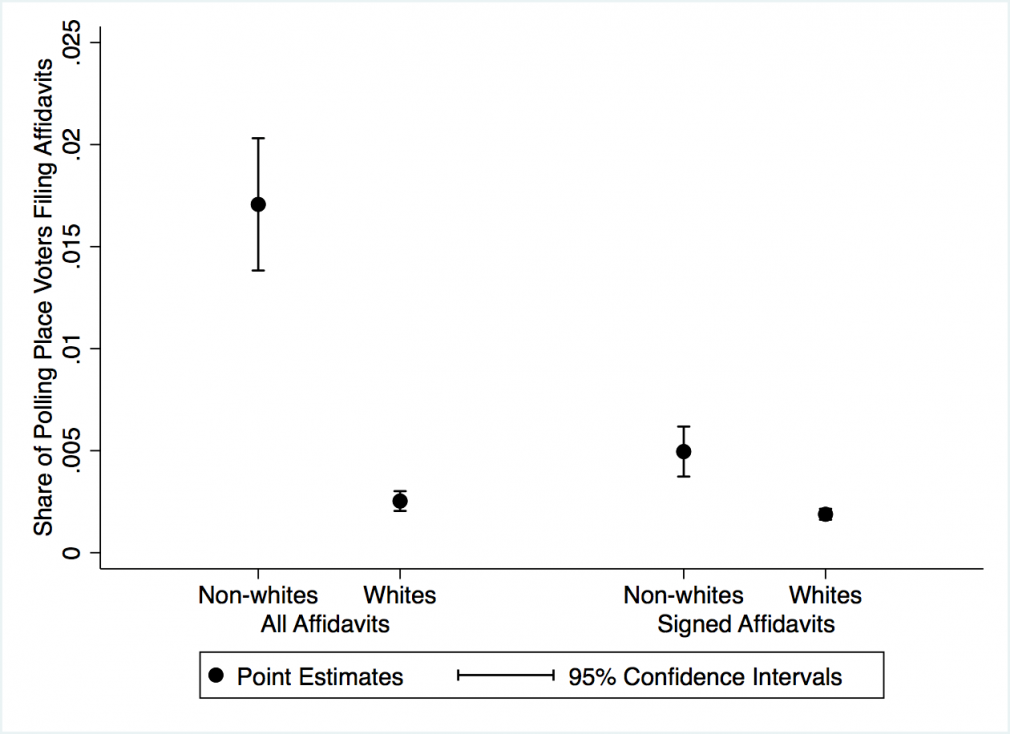

A higher percentage of minority voters than white voters are at risk of being disenfranchised by a switch from non-strict to strict voter ID law. To show this, we first impute the race of every 2016 polling place voter in the Michigan voter file based on surname and residence. We then run a bivariate regression in which the dependent variable is whether someone filed out an affidavit and the independent variable is the percent chance that the voter is white. The results of these regressions, which are displayed in the figure below. show that minorities are 6 times more likely to file an affidavit, and 2.6 times more likely to file a signed affidavit, than white voters.

Findings

In our full paper, we also analyze the relationship between the likelihood of filing an affidavit and an individual’s primary vote history. Given that minorities are more likely to vote for Democrats than whites are, it is not surprising that our analysis suggests that voters who lacked photo identification are more likely to vote for Democrats too. However, we estimate that at least a quarter of affidavit filers would vote Republican.

Our findings are consistent with the claim that there is a potential disparate racial and partisan impact of strict photo ID laws, but the upper bound on the potential number of people affected is much smaller than often asserted. While this suggests that the electoral consequences of shifting from a non-strict to a strict photo ID policy are limited, our single-state case study cannot address the political implications of voter ID laws in their entirety. Instead, it suggests that scholars should spend relatively less time studying the de jure disenfranchisement caused by the shift from non-strict to strict photo ID laws and relatively more time studying the potential de facto disenfranchisement caused by the imposition of non-strict ID laws in the first place.

Election administrators may want to take note of a number of findings in this paper. This research was possible because Michigan creates a paper trail of voters who cast ballots without ID, makes these data available to researchers, and has clerks who are willing to be generous with their time to support our data collection efforts. We hope that other states with non-strict ID laws will make their data available to facilitate comparative studies across states and identify best practices. Such work would be easier if the data were centralized at the state rather than the municipal level, as the local administrative records are particularly difficult to collect.

Beyond facilitating data collection, our data analysis reveals that the placement of affidavits on the back of general use form appears to cause some people to fill out the affidavits even though they have access to ID at the polls. Combined with the fact that election inspectors do not always sign the affidavits, this makes it hard to reconstruct who exactly lacked ID when voting. If doing so is a priority, our results suggest that Michigan may want to hand out affidavits to voters only when required, and to provide further training to election inspectors on how to manage the process when voters lack the requisite ID.

The authors would like to thank the many clerks in Michigan that assisted us in collecting data on affidavits, and Stephen Damianos, Nik Damjanovic, Ketaki Gujar, Katherine Hsu, Theodore Kotler, Charlotte Laracy, and Eric Selzer for their research assistance. We also thank the Penn Program on Public Opinion and Election Studies and University Research Foundation for financial support.