How Many Naked Ballots Were Cast in Pennsylvania’s 2020 General Election?

The MIT Election Data and Science Lab helps highlight new research and interesting ideas in election science, and is a proud co-sponsor of the Election Sciences, Reform, & Administration Conference (ESRA).

Our post today was written by Daniel J. Hopkins, Marc Meredith, and Kira Wang, based on their paper presented at the 2021 ESRA Conference. The information and opinions expressed in this column represent their own research, and do not necessarily represent the opinions of the MIT Election Lab or MIT.

Pennsylvania experienced an unprecedented surge of mail balloting in the 2020 presidential election.

Because of the passage of Act 77 in 2019, the 2020 elections were the first federal elections in which all registered Pennsylvanians were eligible to apply for a mail ballot. The COVID-19 pandemic caused more Pennsylvanians to take advantage of this newfound ability to cast a mail ballot than anyone anticipated. The Pennsylvania Secretary of State reported that 2,704,147 mail ballots were cast in the 2020 presidential elections, which was about 39 percent of the total ballots cast statewide. As a point of comparison, U.S. Election Assistance Commission data show that only 266,208, or about 4 percent, of the 6,223,150 ballots cast in the 2016 presidential election were cast by mail.

Experiencing a ten-fold increase in the number of mail ballots raised the salience and impact of the rules governing what could cause a mail ballot to be disqualified. One issue that arose was how to handle the expected increase in mail ballots that were mailed back before Election Day, but not received by election administrators until afterwards because of a slowdown in mail processing or late sending. A second issue was what information must be completed on the declaration on the mail-ballot return envelope for a ballot to be eligible for counting. A third issue, which is the focus of this blog post, is whether ballots could be counted if they were not returned within a secrecy envelope.

Secrecy Envelopes and Naked Ballots

According to data from the National Conference of State Legislatures, Pennsylvania is one of sixteen states that provides mail-ballot voters with a smaller secrecy envelope that a mail ballot is placed in, which then gets placed within a larger mail-ballot return envelope. What became clear during the 2020 primary election is that Pennsylvania election administrators lacked a common understanding of whether to count mail ballots that were returned without being placed inside a secrecy envelope, which were commonly referred to as “naked ballots.”

Many expressed concern about the number of voters who might be affected when the Pennsylvania Supreme Court clarified in September 2020 that the current state law is that naked ballots are not to be counted. Media reports highlighted cases in Lawrence and Mercer counties in which more than 5 percent of mail ballots returned in the June 2020 primary were rejected because they were naked ballots. Similarly, about 6.4 percent of the 3,086 mail ballots cast in the 2019 general election in Philadelphia were rejected for not being enclosed within a secrecy envelope. Philadelphia City Commissioner Lisa Deeley, the chairwoman of the board that oversees the election administration of elections in Philadelphia County, wrote a letter to the Pennsylvania State Legislature noting that she believed that Philadelphia counted at least 15,000 mail ballots that were returned outside of a secrecy envelope in the 2020 primary election and that this extrapolated to about 30,000 to 40,000 Philadelphians potentially being at risk of having their votes invalidated in the 2020 general election if the law mandating the disqualification of naked ballots was not changed.

Massive voter-education efforts quickly sprung up after the September 2020 court decision to inform voters about the necessity of putting a mail ballot inside of a secrecy envelope to prevent it from being disqualified. One primary avenue of voter education was through social media, with Instagram accounts such as @nakedballot using memes and infographics to emphasize the importance of putting mail-in ballots in their secrecy envelopes. Furthermore, grassroots campaigns such as RepresentUs had celebrities such as Mark Ruffalo and Amy Schumer star in ads that highlighted Pennsylvania’s new voting laws. Similarly, Allegheny County election officials also created eye-catching ads that featured them posing naked next to instructions on how to cast a “dressed” ballot. In addition, political parties quickly acted to combat the implications of the naked ballot ruling. A spokesman for the Pennsylvania Democratic Party described its education campaign about naked ballots as a “all-hands-on-deck effort from us and the Biden team and the DNC all kind of working hand in hand to make sure that we spread the word and educate voters.”

Despite the salience of naked ballots in the 2020 general election, no one has compiled data allowing us to understand how many naked ballots were cast statewide in the 2020 general election. Media reporting on the number of naked ballots in specific countries suggests that the share of mail ballots returned outside of their secrecy envelopes was lower than some feared, likely because of the voter education campaigns described in the previous paragraph. Philadelphia City Commissioners spokesperson Kevin Feeley reported only approximately 4,027 naked ballots cast (only 1.1 percent of mail ballots returned by city residents) in the 2020 general election instead of the 30,000 to 40,000 that Deeley projected. A media report indicated that about 1 percent of returned ballots were naked in the south-central Pennsylvania counties of Franklin, Lebanon, and York as well. The share of naked ballots may have been even lower in Allegheny County — home to Pittsburgh — with reported estimates of around 2,000 naked ballots out of about 300 thousand mail ballots cast. Similarly, court documents indicated only 708 naked ballots in Bucks County, a suburban Philadelphia area county, out of almost 140,000 mail ballots cast.

Our Research

To gain a more systematic understanding of the number of naked ballots cast in the 2020 general election, we sent public information requests to all 67 Pennsylvania county board of elections. In this request, we asked each county for information on the number of mail ballots returned outside of their secrecy envelope and the number of total mail ballots rejected in the 2020 primary, 2020 general, and 2021 primary elections. We first sent an email request on June 24, 2021, following up with a postal mail request to counties that didn’t respond on July 14, 2021. We called the county election board during the week of July 26, 2021 if both of these requests went unresponded.

Not all of the counties that responded to our request were able to provide information on the number of ballots returned outside of the secrecy envelope, especially in the 2020 primary election. 32 of the 55 counties who responded were able to provide exact information on the number of naked ballots in the 2020 general election. This does not include the small number of counties reporting zero naked ballots, which we omit out of concern that they did not understand what we were asking for. Combined, about 36 percent of the mail ballots cast in the 2020 general election were cast in these counties. Similarly, 28 of the 55 counties, in which about 43 percent of the mail ballots were cast, provided information on the number of naked ballots cast in the 2021 primary election. In contrast, only 5 counties provided information on the number of naked ballots cast in the 2020 primary election.

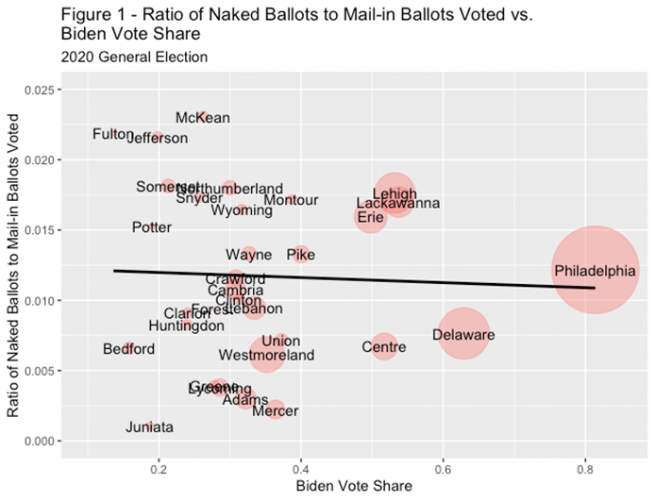

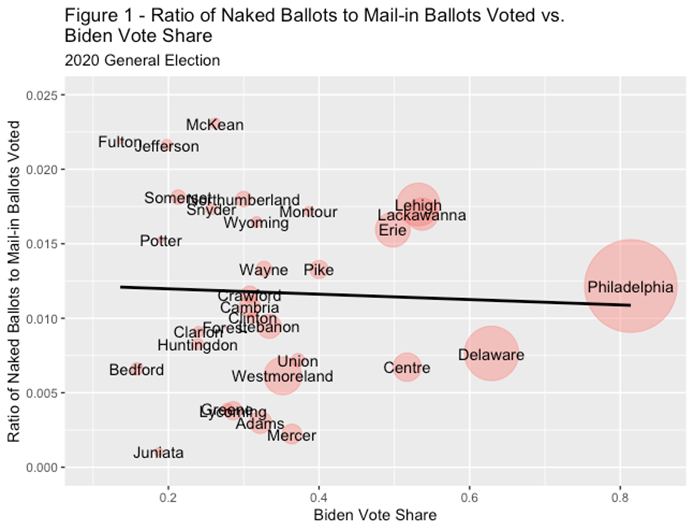

Figure 1 displays the ratio of naked ballots cast in the 2020 general election to the number of counted mail ballots as a function of Joe Biden’s vote share in the county. Figure 1 indicates that just over 1.1 percent of the mail ballots cast in these counties were naked ballots. The trend line also does not show any clear difference in the rate of naked ballots as a function of Joe Biden’s vote share in the county.

Figure 1, showing the ratio of naked ballots to mail-in ballots voted versus Biden vote share in the 2020 general election.

While ballot curing policies are one factor that could have caused some of the differences observed in the rates of naked ballots over counties in Figure 1, we doubt it is the primary factor. While counties were not allowed to open ballots until Election Day, election administrators may be able to tell before Election Day when a mail ballot is not enclosed in a secrecy envelope based on its weight. Counties handled this situation in different ways ranging from immediately canceling the ballot, contacting the voter, mailing the ballot back to the voter, or doing nothing at all. Counties also differed in whether they attempted to contact voters when they discovered that they cast a naked ballot when opening their mail-ballot envelope on Election Day. Counties that gave voters more opportunities to cure their naked ballots may report a smaller rate of naked ballots if they exclude naked ballots that were ultimately cured. However, the limited evidence that exists on curing suggests that not that many ballots were cured. For example, Montgomery County, a suburban Philadelphia area county, had 93 voters whom they contacted prior to Election Day cure their problematic mail ballots out of 208,000 mail ballots cast.

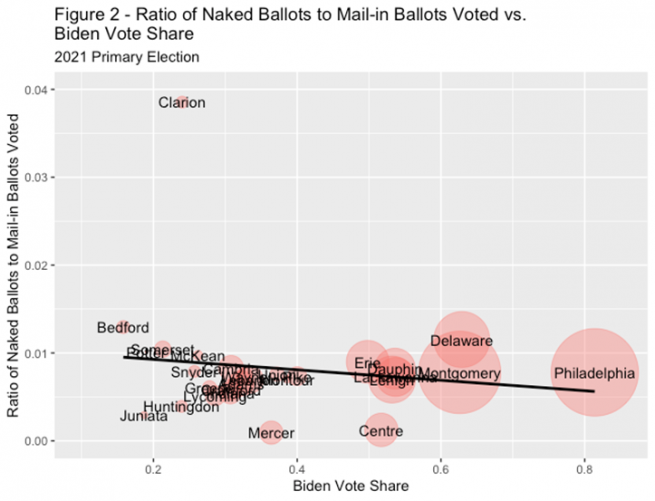

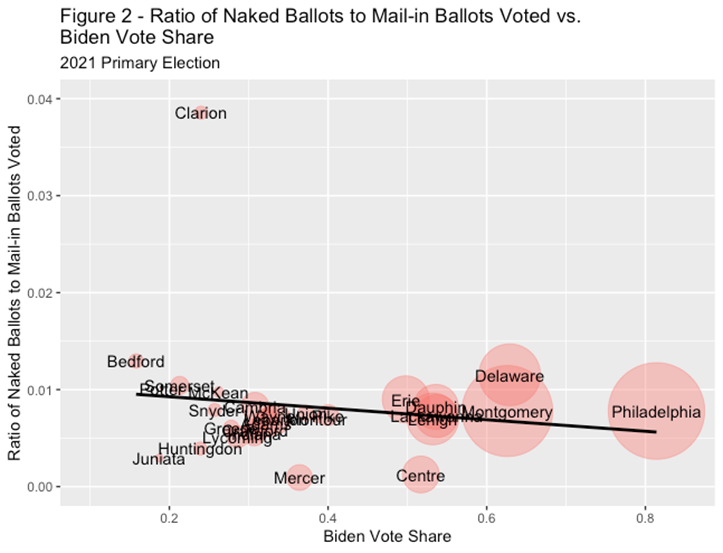

Figure 2 replicates Figure 1 for the share of mail ballots rejected in the 2021 primary election. Figure 2 shows that about 0.8 percent of mail ballots cast in the counties that provided data were naked ballots. We believe that differences in the types of registrants who vote in a presidential election and municipal election explain some of the differences in the incidence of naked ballots in the 2020 general and the 2021 primary. Because the electorate in municipal primary elections tends to be highly educated and experienced with voting, we expect municipal primary voters to be less prone to casting mail ballots that get rejected because of clerical errors than presidential election voters.

Figure 2, showing the ratio of naked ballots to mail-in ballots voted versus Biden vote share in the 2021 primary election.

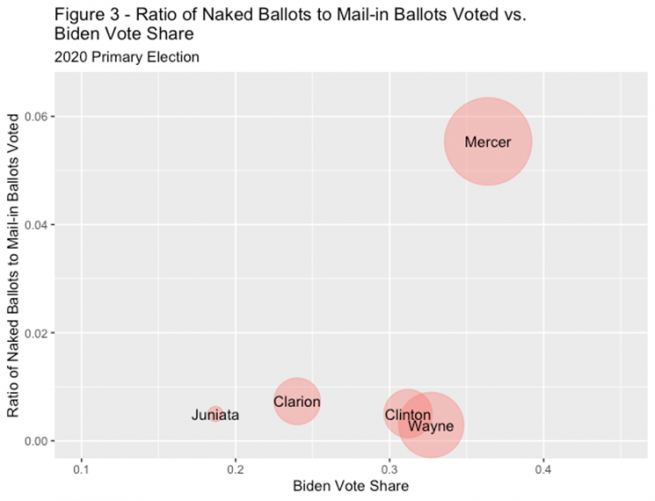

It is hard to compare how often naked ballots were cast in the 2020 general and 2021 primary elections with the 2020 primary election because few counties were able to provide information on the number of ballots returned outside of a secrecy envelope in the June 2020 election. What Figure 3 does make clear is that not all counties were experiencing the same high rate of naked ballots in the 2020 primary election that media reports highlighted in Lawrence and Mercer counties. The other four counties that reported information on the number of naked ballots in the 2020 primary reported numbers that were more in line with the numbers reported in the 2020 general and 2021 primary.

Takeaways

One thing we take away from this research is that Pennsylvania needs to standardize a process for tracking naked ballots. At minimum, all counties should be quickly able to report how many ballots they rejected because they were not enclosed in secrecy envelopes or for any other reason. But even better would be a requirement to distribute individual-level data on ballot rejection by reason so that observers can better understand who is casting rejected ballots and inform strategies that might be used to reduce their incidence.

Another lesson from this research is that we should not assume that the rate of mail ballot rejection in the 2020 general election in Pennsylvania is predictive of what the mail ballot rejection rate will be moving forward. We observed that many counties rejected a substantially higher share of the mail ballots returned in the 2021 primary election than in the 2020 general election, despite our expectation that the types of voters who participate in municipal primary elections would be less likely to make clerical errors that cause mail ballots to be rejected than presidential election voters. For example, Bedford County, a small county in south-central Pennsylvania, reported rejecting about 4.6 percent of the mail ballots it received in the 2021 primary election as compared to about 0.7 percent of the mail ballots it received in the 2020 general election.

In most cases it does not appear that naked ballots are the primary cause of most of the observed increases in rejected mail ballots, although Figure 2 reveals that this did appear to occur in Clarion County, a small county in Northeast Pennsylvania. In Bedford, for example, ballots not returned in a secrecy envelope caused 31 of the 35 mail ballot rejections in the 2020 general election, but only 19 of the 70 mail ballot rejections in the 2021 primary election. Differences in rules explains some of the increased rejection. About 2 percent of mail ballots were rejected in Bedford in the May 2021 primary because they were received after Election Day, nearly all of which would have counted in the 2020 general election. Likewise, Philadelphia County rejected about 2 percent of the mail ballots cast in the May 2021 primary because voters failed to date the signature on the mail ballot return envelope’s declaration, which did not disqualify a mail ballot in the 2020 general election.

Counties also experienced problems in the 2021 primary election that weren’t present in the 2020 general election, perhaps because of the reduction in voter education efforts leading up to the election. Bedford County, for example, rejected about 1 percent of the mail ballots cast in the 2021 primary election because they were put into a secrecy envelope that was not properly sealed after not rejecting any ballots for that reason in the 2020 general election. This makes us concerned about the potential for voter disenfranchisement under the rules governing mail balloting in Pennsylvania moving forward, especially when there is not the same degree of voter education and ballot curing efforts that were present in the 2020 general election.