MEDSL Explains: Provisional Ballots

Imagine for a moment: Election Day has arrived. You’ve taken your lunch break a little early to go vote. (You thought about going before work, but you read up on the report that found lines are longest in the morning, when the polls first open.)

“Sorry,” the poll worker says when you get to the top of the line. “I don’t see your name; are you sure you’re registered to vote here?”

You’re definitely sure. You filled out the forms last year when you moved and had to change your driver’s license, and your neighbor let you know last week where the polling station was after its location changed.

The poll worker is calling someone else over as you try to explain. You’re sure you’re the right place. They have to let you vote, right?

Now what?

Luckily for the fictional you, your state has provisional ballots, as (almost) all states have been required to use since the Help America Vote Act (HAVA) became law in 2002. The day — and your vote — is saved!

Well, probably saved. Provisional ballots can (surprise!) be complicated. Let’s take a closer look at why they exist, and how the system works.

What's a provisional ballot?

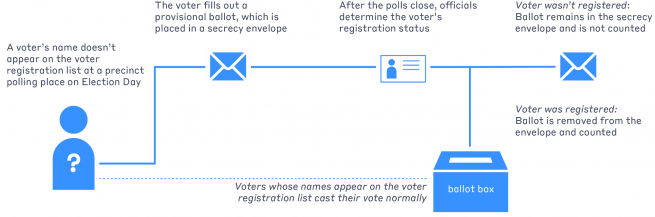

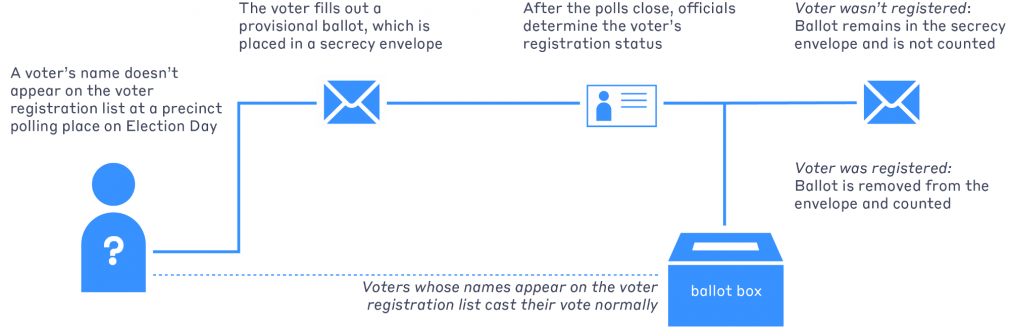

Ultimately, provisional ballots are intended to provide fail-safe protection for voters if there are questions about their registration status on Election Day. In its most basic form, a provisional ballot works like this: A voter arrives at a precinct polling place on Election Day, but their name doesn’t appear on the voter registration list — even though they believe they are, in fact, registered. Rather than being turned away entirely, they may be offered a provisional ballot. After being marked, that ballot is placed in a special secrecy envelope rather than in the ballot box. Once the polls close, the actual registration status of the voter is determined. If the voter was registered on Election Day, the ballot is removed from the secrecy envelope and counted, just like any other ballot. If it turns out the voter wasn’t registered, for any number of reasons, the ballot remains in the secrecy envelope and is not counted.

Beyond that basic functionality, though, how are provisional ballots implemented? The answer is that it varies — significantly — across state lines, reflecting differences in state law as well as cultural practices from state to state. And although provisional ballots are intended to ensure that no voter is prevented from casting their ballot when there are questions about their registration, controversy persists over whether the use of provisional ballots are a positive or negative part of election administration.

HAVA: Before & After

The 2000 election provided impetus for broad changes to provisional balloting (as it did for many election-related policies and systems). Up until that point, only 17 states and the District of Columbia had some form of provisional balloting. An additional seven states had voter registration systems that made provisional ballots irrelevant — either because they had Election Day Registration (EDR) or no voter registration at all. In 2000, though, evidence that hundreds of thousands of voters were turned away at the polls because of voter registration errors helped pave the way for a section within the 2002 HAVA that mandated states adopt provisional balloting unless EDR made them irrelevant.

Since then, all states have been required to use provisional ballots; the only exceptions to this rule were states that offered same-day registration when the National Voter Registration Act was enacted in 1993. Even most of these states, though, have found provisional ballots useful in certain situations.

When HAVA arrived on the scene, there was no consensus among the states about how provisional ballots should be implemented. Some of the debates on this point are still going on: one important question, for example, continues to be whether a provisional ballot should be counted if the voter is registered to vote in the jurisdiction, but shows up to vote at the wrong precinct.

In this situation, most states reject provisional ballots. The states that do count “out-of-precinct” provisional ballots also have some restrictions on how and when those votes are counted. If a vote is cast in the wrong precinct, for example, the state only counts the voter’s choices for offices that they were eligible to vote for in their correct precinct. So, a voter who casts a provisional ballot in the wrong precinct would not be able to vote for that precinct’s school board candidates, because it’s not a race they’re eligible to vote for in their own precinct. But they could vote for the district’s new state representative, if the race for that particular seat was also on the ballot in their own precinct.

A second major policy choice that states face is how aggressively to give out provisional ballots, and whether to encourage their use as a way to record voters’ address changes on Election Day. Allowing provisional ballots to be used for this purpose makes address changes more convenient for voters, but it increases paperwork and may increase the likelihood that a vote will not be counted because of a clerical error.

Voting provisionally today

According to the 2016 Election Administration and Voting Survey compiled by the U.S. Election Assistance Commission, at least 2.5 million provisional ballots were issued in the 2016 federal election. 1.7 million were counted, at least in part — which accounted for 1.2% of all votes counted in that election. 600,000 provisional ballots were rejected, or about 0.4% of ballots cast. (About 100,000 provisional ballots were statistically unaccounted for.)

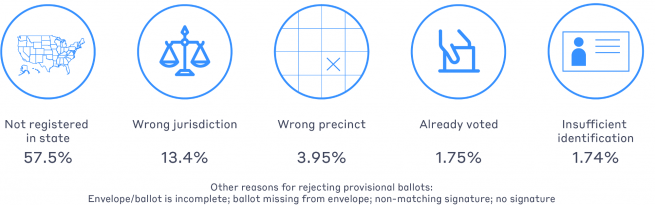

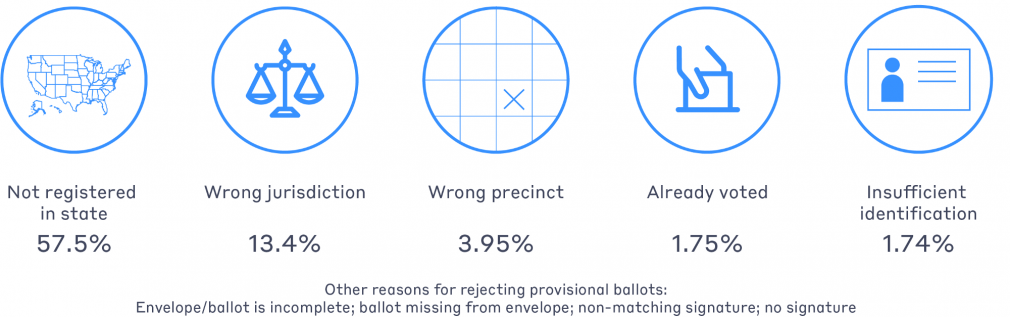

The most common reason provisional ballots are rejected is that a voter was not on the voter list in the state — this actually accounts for half of all rejections. Following that, the second and third most common reasons that provisional ballots are rejected are that the voter was registered in another jurisdiction in the state, or that the voter tried to vote in the wrong precinct in their jurisdiction. (These reasons together account for another quarter of all rejections.) Less frequently, provisional ballots can also be rejected when voters have the wrong ID or have already voted, or if the signature on the provisional ballot application does not match the registration record on file.

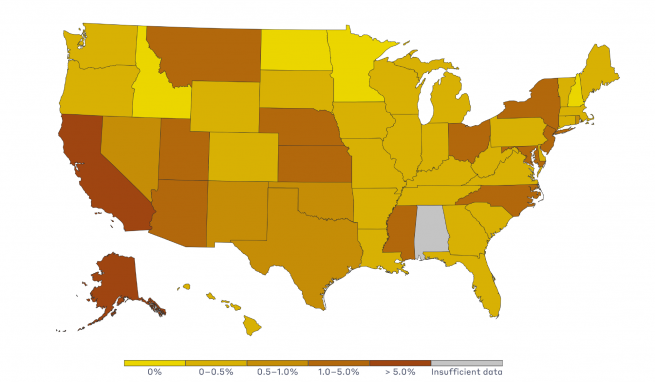

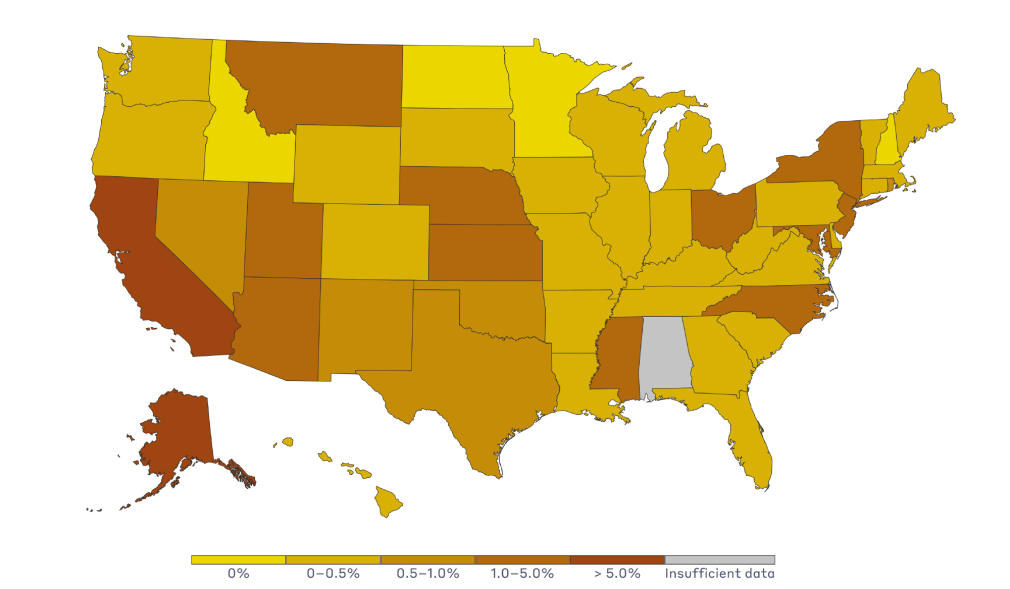

Across states, there is significant variability in the distribution rates of provisional ballots. You can see some of this variability in the map below — if we leave aside the states that aren’t required to use provisional ballots, the percentage of voters in 2016 who submitted a provisional ballot ranged from almost zero to over 5%. The state in 2016 with the lowest proportion of provisional ballot use was Vermont, which saw only 0.3%; California had the most, with 8.8%:

Provisional ballots distributed, as a percentage of all ballots cast in the 2016 election. (Source: U.S. EAC, 2016 Election Administration and Voting Survey)

One of the strongest predictors of how many provisional ballots a state will issue turns out to be whether the state used provisional ballots before HAVA. For states that had used provisional ballots before HAVA, the average rate of provisional ballot distribution in 2016 was 2.0% — whereas in states that didn’t adopt provisional ballots until after HAVA was enacted, the rate was only 0.69%.

In addition, many of the states with the highest provisional ballot usage rates also have permanent absentee ballot lists. In these states, if a voter who is on the permanent absentee ballot list shows up on Election Day to vote, they’re often required to submit a provisional ballot to ensure that they haven’t already cast an absentee ballot that is still on its way in the mail.

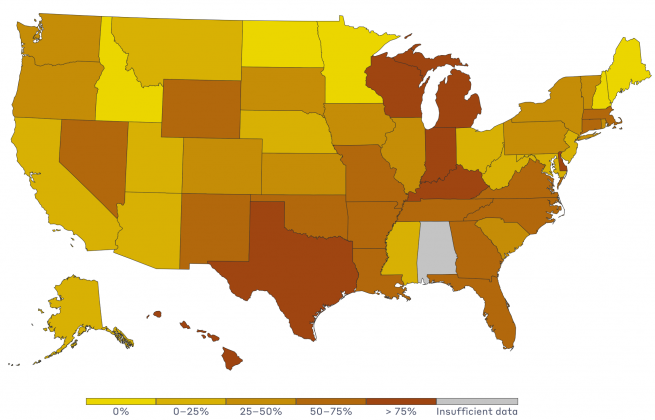

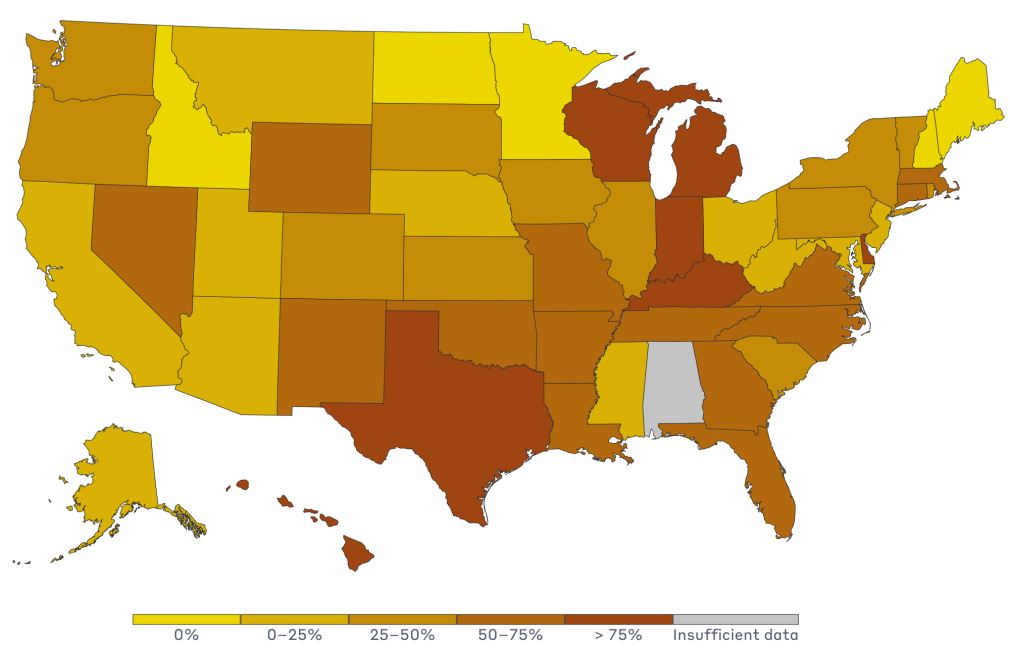

If we look back at rejection rates for provisional ballots, we can see that states also vary significantly in how many of these ballots they reject. States that have higher rates of provisional ballot usage tend to have low rejection rates, and vice versa. Alaska, for example, distributed provisional ballots to 6.1% of its voters (the second-highest rate in the country), and had the lowest rejection rate, at 1.4%. On the other hand, Delaware had the nation’s highest rejection rate (a whopping 92%), and only gave provisional ballots to 0.07% of its voters — the ninth-lowest rate in the country.

Percentage of provisional ballots that were rejected in 2016. (Source: U.S. EAC, 2016 Election Administration and Voting Survey)

At a more local level, variability in provisional ballot distribution is associated with demographics and political factors. Jurisdictions with younger, more mobile, and more minority voters distribute provisional ballots at higher rates. Perhaps unsurprisingly, more provisional ballots are distributed in presidential election years than in midterm elections.

Are provisional ballots good?

It makes sense that a fail-safe mechanism to protect voters against registration errors is a good thing for an electoral system to provide. Without that mechanism, the 1.7 million provisional ballots that were counted in 2016 could have potentially been 1.7 million “lost votes” instead, left unrecorded through no fault of the voter.

But — there is almost always a but — some voting rights advocates have argued that the availability of provisional ballots makes it too easy for local jurisdictions to shirk their efforts to maintain accurate voter lists. Processing provisional ballots can be affected by clerical errors, leaving open a small chance that any provisional ballot that should be counted will instead be rejected, regardless of whether the voter was actually registered.

Additionally, a provisional ballot given to a registered voter who has shown up in the wrong precinct is usually not counted at all. In these cases, there is a debate over whether poll workers should be more insistent in telling these “wrong-precinct” voters to go to the right precinct, rather than issue ballots that won’t be counted.

Ultimately — to bring us full-circle back to 2000 and the emergence of provisional ballots into law — it’s also important to note that because provisional ballots are processed after elections, they can become the target of litigation in the event of a recount. (Absentee ballots are the other form of ballot that runs this risk.) In states with a high number of provisional ballots, even if the rejection rate is generally low, the existence of provisional ballots at all becomes an easy target for controversy during a recount.

For more information on provisional ballots, don’t miss the recent post by Thessalia Merivaki and Daniel A. Smith: “Who Votes Provisionally and Why?”