MEDSL Explains: Voter ID

Voter ID is a hot topic in politics these days. But what’s the history of ID laws, and what does the research say about them?

Every state in the US has voter identification requirements. But — plot twist — every single one of those states goes about these requirements in its own particular way. Some states ask you to simply announce your name when you walk in to vote. Others require an official ID card with your photo on it. The rules vary widely, and for nearly two decades, voter ID has been a source of political controversy around the country.

With all the press coverage in the last few years, chances are that if you’re in the US, you’ve heard a little about this controversy by now. To quickly summarize:

- Supporters of more stringent voter ID requirements argue that they deter voter fraud and instill confidence in the integrity of the electoral process.

- Opponents argue that voter fraud is very rare, so the only effect strict ID requirements have is to raise the barriers to voting in ways that disproportionately affect citizens who are already marginalized.

The recent increase in strict voter ID requirements has led to a number of lawsuits alleging racial discrimination. The rise of these laws has also led to an increase in scholarly research into the effects these laws have on voter turnout. There are a host of interesting articles about the legal and political sides of things — but we’ll let you read those at your leisure. Follow on with us here for a dive into the history and the data.

Current requirements: What’s on the books?

In 2002 (following the infamous 2000 presidential election), Congress passed the Help America Vote Act (HAVA), which laid down basic minimum requirements for voters in federal elections in every state. Under HAVA, first-time voters who register by mail are required to show some form of ID, while first-time voters who register in person aren’t. Beyond this “HAVA minimum,” states are allowed to change identification requirements for all voters as they think is necessary, whether or not those voters are casting a ballot for the first time.

Typically, states that follow HAVA-minimum requirements ask voters to announce their name and address at a check-in table when they vote in person. Many of these states also require the voter to sign in. (Regardless of where you are, falsely claiming to be a registered voter is voter impersonation fraud, and is a felony in most states.)

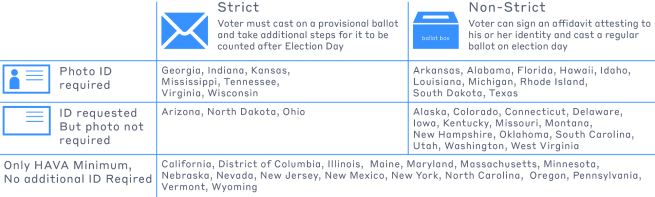

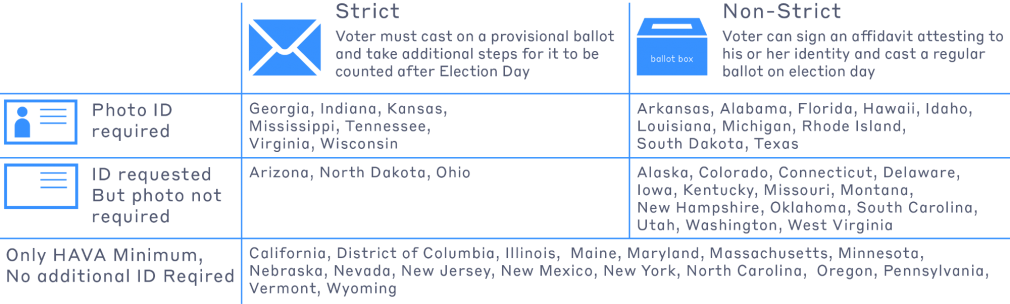

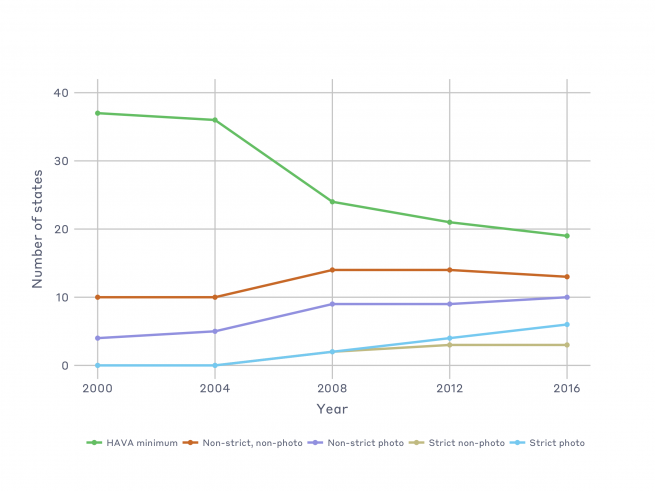

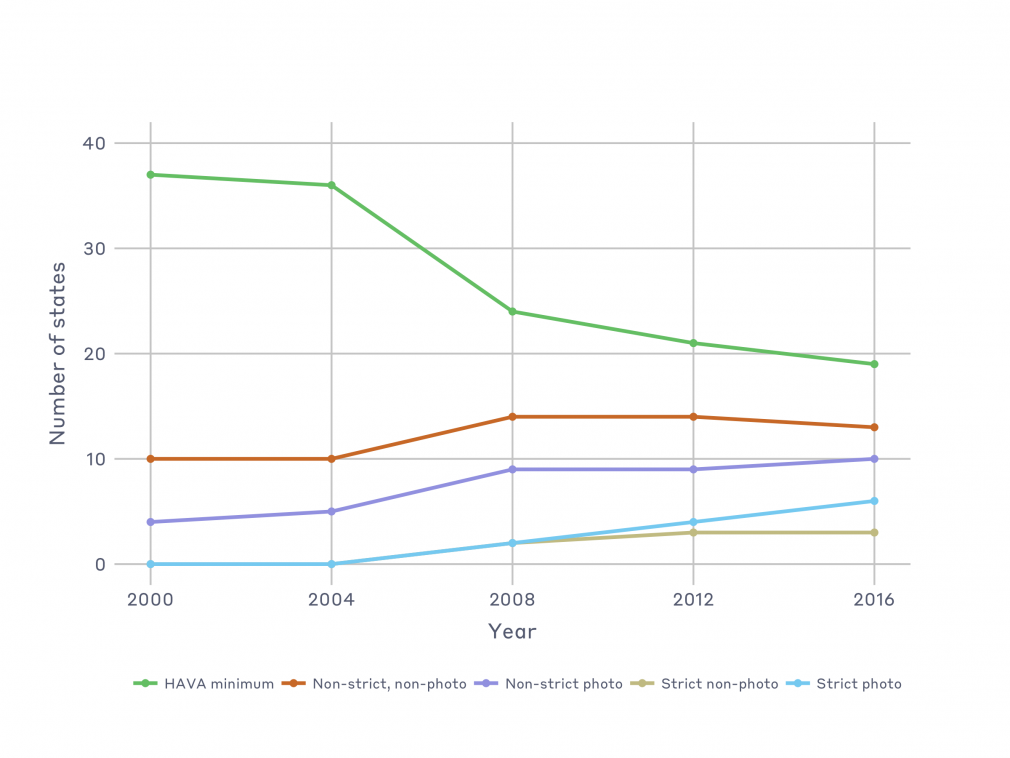

There’s a useful two-dimensional classification system that the National Conference of State Legislatures (NCSL) created to describe the types of voter identification requirements that states put in place beyond the HAVA minimum. The first dimension indicates whether the state requires voters to show a photo ID. The second dimension is what happens when a voter doesn’t have the right kind of ID: “strict” states require that voters cast a “provisional” ballot, and then take some additional steps after Election Day in order for their ballot to be counted. “Non-strict” states, on the other hand, allow voters without proper ID to cast a regular ballot on Election Day once they sign an affidavit attesting to their identity:

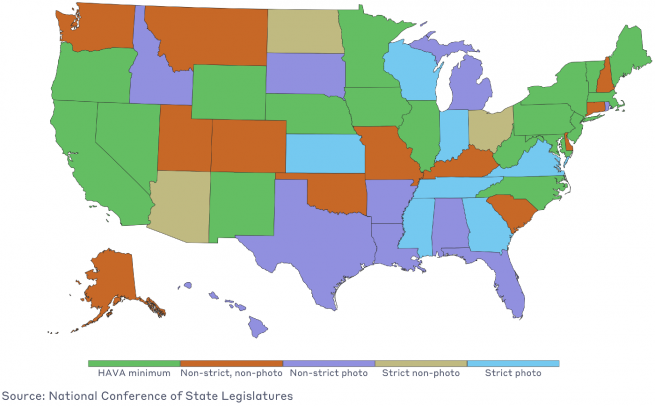

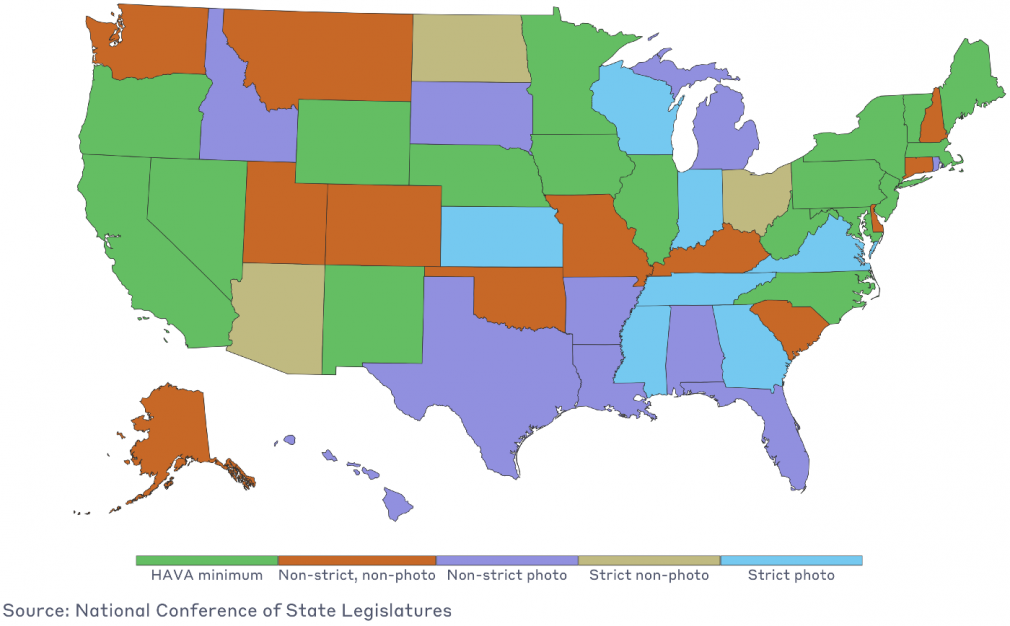

The following map gives a birds-eye view of voter ID laws on the books as of the summer of 2017. From this, it’s easier to see where the strictest ID laws are (generally in the South and Great Lakes states) as well as the least strict (generally in the Northeast and West Coast states):

State voter ID laws are very detailed, so this article provides only a summary of voter ID policy. If you’re interested in the details of voter ID laws in your state, consult your state or local election officials. The U.S. Vote Foundation also has a look-up tool with useful state-specific election information.

With one major exception, voter ID laws only apply to those who vote in person. (The exception to this rule is first-time voters who register by mail. Under HAVA, these voters must include a photocopy of their identification if they vote for the first time by mail.) Identifying voters who cast their ballots by mail, whether they send a traditional absentee ballot or a vote-by-mail ballot, is usually done by matching the signature on the outer return envelope with the signature that election officials have on file.

Legal controversy

Prior to the 2000 election, voter ID laws weren’t especially controversial. Most states had the equivalent of HAVA-minimum requirements, although some went a little further, with non-strict, non-photo ID laws.

Efforts to require photo identification to vote were given a boost by two efforts that followed the 2000 presidential election controversy:

- First, Democratic sponsors of HAVA included ID requirements for first-time voters as a concession to Republicans in order to get the law passed in the Senate.

- Second, in a 2005 report, the Commission on Federal Election Reform (the Carter-Baker Commission) recommended that all states put photo ID requirements in place.

The first state to pass a strict voter photo ID requirement was Indiana, which implemented the standard in 2005. The law was immediately challenged by the Democratic Central Committee in Marion County (which includes Indianapolis). The Committee argued that the law imposed an undue burden on voting rights under the 14th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, but both the federal trial court and the circuit court of appeals rejected those claims.

Following those decisions, the U.S. Supreme Court agreed to hear the case — and in Crawford v. Marion County Election Board, the justices ruled that states had a reasonable interest in preventing election fraud and that photo ID laws were not, on their face, unconstitutional. In upholding the Indiana law, however, the court opened up the possibility that the particular facts surrounding other states’ ID laws could be used to strike them down.

The 2008 Crawford decision was seen as a green light by both supporters and opponents of stricter ID laws. To supporters, Crawford signaled that “reasonable” ID requirements, motivated by a desire to prevent voter fraud, would likely be found constitutional. To opponents, the decision laid out a possible path to future challenges. Although the Supreme Court ruled that photo ID laws were not unconstitutional on their face, it did signal that if opponents could show specific harms to voters that outweighed states’ interests in curbing fraud, strict voter ID laws might be struck down.

The number of states having some sort of voter ID requirement rose significantly between the presidential elections of 2004 and 2008 — you can see that trend illustrated in the graph below. The fastest-growing categories of ID laws involved photo identification, but most states with photo ID requirements still fall into the “non-strict” category.

Another factor that spurred the passage of ID laws — especially strict photo ID laws — was a second decision by the Supreme Court.

In 2013, the Court heard Shelby County v. Holder, which related to the federal preclearance provisions of the Voting Rights Act (VRA). Before this case, states that were “covered” under Section 5 of the VRA (mostly states that seceded during the Civil War) were required to have any changes to their election-related voting procedure precleared by the Justice Department. To be granted preclearance, a state covered by Section 5 would have to show that an ID law did not have a racially discriminatory intent or effect. Although Section 5 did not entirely stop the passage of stricter photo ID requirements — Georgia’s strict photo ID law was precleared by the Department of Justice in 2006 — it did put a damper on states that might have otherwise tried to pass them.

Shelby County effectively gutted preclearance when the Court decided that the formula that identified “covered” jurisdictions, which was outlined in Section 4 of the VRA, was outdated. After the case, southern states began adopting stricter ID laws — North Carolina and Texas, for example, quickly enacted photo ID laws that were far stricter than those passed in the previous decade. In turn, however, these laws were challenged under a different section of the VRA, Section 2.

Currently, both North Carolina’s and Texas’s laws are on hold following adverse federal court decisions. Another photo ID law, in Pennsylvania, is also on hold because of action from the state court.

Research on voter ID

The scholarly community has directed intense focus on the subject of voter ID. A topic of particular interest has been the impact that photo ID laws have on racial minority groups and turnout in elections.

Public opinion research has found that minority voters tend to possess photo IDs at lower rates than whites. In the 2016 Survey of the Performance of American Elections, for instance, only 7% of white respondents did not have either a driver’s license or passport, compared to 17% of black respondents and 9% of Hispanics. Research associated with litigation that has matched voter rolls against lists of drivers’ licenses has confirmed this finding in more than a few states, including North and South Carolina, Pennsylvania, Texas, and Wisconsin. (Whether those differences have been enough to overturn the laws, on the other hand, has varied across different courts.)

Whether the lack of IDs leads to a decrease in turnout is still open to dispute. Some early studies found no statistical association between strict ID laws and decreased turnout (see, for example, articles by Ansolabehere and Mycoff et al). More recent studies by the GAO and Hajnal et al have shown negative correlations between strict photo ID laws and turnout, and the debate — far from concluding — continues as more scholars scrutinize the issue.

Importantly, as of yet there has been no large-scale study to examine the effects of ID laws on turnout using a research design that can validly estimate the causal effects of these laws. In a methodological article, Robert Erikson and Lorraine Minnite note that the data sets that have been used to study the turnout effects of ID laws are currently too small to accurately measure any causal effects. On another front of the same issue, while it may seem obvious that voter ID laws can only serve to depress turnout, important arguments have been made by scholars that the very presence of voter ID laws can have a counter-mobilizing effect that encourages greater turnout among voting populations that are targeted by those laws.

Another important research issue is whether ID laws are implemented consistently as written. Based on studies involving close observation of poll workers, at least two articles suggest that inconsistent implementation may be common.

Still another interesting aspect of voter ID laws is the effect of these laws on the confidence of voters. Research into this question was partially inspired by the argument of the Supreme Court in Marion County that a rational justification for a state passing a strict ID law is to instill greater confidence in the electoral process. This seems like a logical argument to make. However, the research conducted on this question (see, for example, here and here) has not found a consistent correlation between the presence of strict ID laws in a state and an increase in voter confidence (or a decrease in the belief that fraud is rampant).

Finally, scholars have also studied the factors that lead states to adopt strict ID requirements in the first place. Strict ID laws are fairly popular among all members of the public, including Democrats, minority groups, and liberals — but Republicans, conservatives, and whites are more likely to approve of these laws. What prompts a state legislature to adopt a strict photo ID law appears to be a confluence of three factors:

- a Republican takeover of the state government after a period of Democratic control,

- being a “battleground state” (i.e., a state that’s usually hotly contested by political parties), and

- being racially heterogeneous.

While these three factors aren’t necessarily present in every state that adopts a strict photo ID law, they are common to most.

As a whole, there is still a lot that we don’t know about voter ID requirements and the effects these standards have on states, citizens, and voter turnout. New research continues to emerge, though, and we look forward to hearing from more scholars and policy-makers on the different — often complicated — aspects of the issue.