MEDSL Explains: Voter Registration

A look at the history & current innovations in registering and counting U.S. voters

Efforts to expand the right to vote or access to the polls have focused on making voter registration available to more Americans. Agreeing on what those efforts should look like, though, has proved difficult. Should registration opportunities be expanded or limited? How vigorously should states purge voter rolls of “deadwood” — that is, people who have died or moved out of state?

Although voter registration has been the subject of recent controversy, it hasn’t always been necessary for Americans to register before voting. To this day, in fact, one state (North Dakota) has no voter registration requirement at all.

Most laws and regulations relating to elections are handled by the states. There are some federal laws guiding voter registration nationwide, however; the most important of these are the 1965 Voting Rights Act (VRA) and the 1993 National Voter Registration Act (NVRA). The VRA prohibits racial discrimination in voter registration. The NVRA requires that states make voter registration widely available, and limits what they can do to remove voters from the rolls.

In recent years, a number of states have worked to implement new ways to register, including online and automatic voter registration. Many of these innovations were designed to help voters register correctly and easily, but they also help election officials deal with administration challenges surrounding voter registration. For example: millions of registered voters move from one election jurisdiction to another each year, which creates distinct challenges for the officials trying to keep the voting lists up-to-date, and contributes to the “deadwood” problem described above.

Background

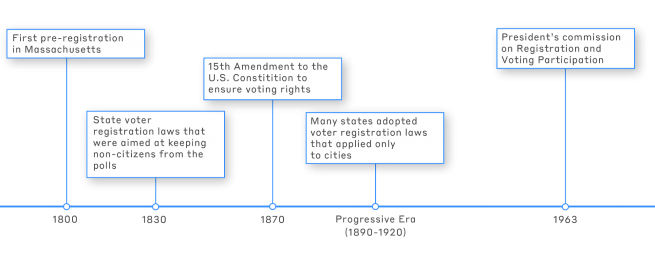

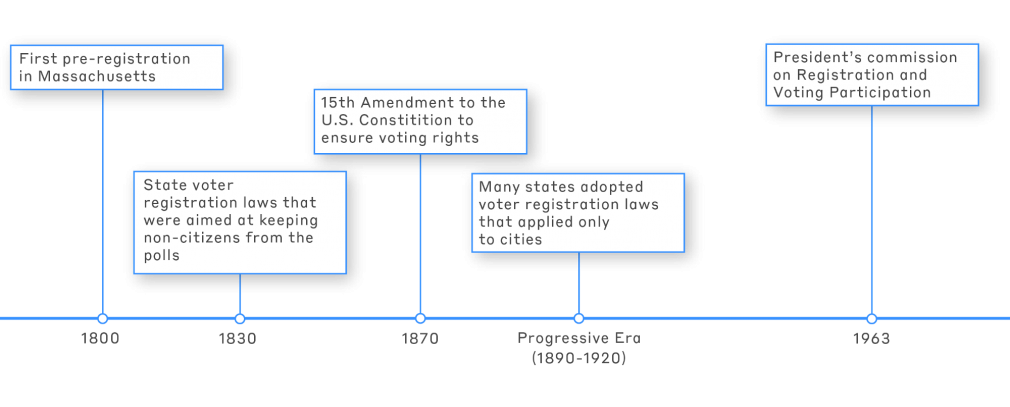

Preregistering to vote hasn’t always been a requirement for citizens who want to cast a ballot. In the earliest years of the republic, it was assumed that local officials personally knew the small number of residents in their towns who met the property qualifications to vote. It wasn’t until 1800 that Massachusetts instituted the nation’s first preregistration requirement.

The earliest registration processes were mostly used to enforce the requirement that qualified voters had to pay their taxes. Anti-immigration agitation in the 1830s saw another wave of state voter registration laws that were aimed at keeping non-citizens from the polls. (Until then, several states granted non-citizens the right to vote.) Still, throughout most of the 19th century, preregistration was not a requirement to vote in all states.

Voter registration that resembles modern practices began in the late 1800s when states expanded their registration requirements, paying particular attention to controlling the voting of city dwellers, immigrants, and African Americans. During the so-called Progressive Era (1890–1920), many states adopted voter registration laws that applied only to cities. Among the reasons for this specificity was the desire of rural-dominated state legislatures to blunt the political power of rapidly growing urban areas, which were growing largely through the influx of new immigrants. In addition, stories of political corruption and vote fraud, such as “repeat voting,” tended to arise most often in urban settings.

Despite the ratification of the 15th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution in 1870 stating that the “right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged… on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude,” the late 1800s witnessed the enactment of many laws that denied African Americans their newly won constitutional rights. As chronicled by C. Vann Woodward’s classic book, The Strange Career of Jim Crow, the official disfranchisement of African Americans became especially aggressive in the South at a time when black politicians were just becoming successful in forming coalitions with blocs of whites. In addition to imposing extraordinary voting requirements such as literacy tests that disadvantaged black citizens, Southern voter registration in general was becoming increasingly burdened by registration regulations.

State voter registration laws that sprang up at the turn of the twentieth century applied to voters of all races and deterred the participation of all but the most persistent citizens. For instance, many states required voters to register annually, or removed voters from the rolls if they failed to vote in an election. Registration closing dates — the date on which the voter registration rolls were closed before an upcoming election — were often months ahead of elections. Even as late as 1972, five states cut off registration more than a month before an election.

The civil rights movement that succeeded in passing the Voting Rights Act also spawned related movements that called for lowering voter registration barriers for reasons other than race. The President’s Commission on Registration and Voting Participation appointed by President Kennedy in early 1963 recommended a series of reforms to ease voter registration, most of which were eventually adopted. Among these were reducing the gap between registration closing dates and elections, reducing residency requirements, and increasing opportunities to vote absentee.

NVRA

The National Voter Registration Act (also known as the “NVRA” or the “Motor Voter Act”) of 1993 represented the culmination of a quarter-century of efforts to relax the strict voter registration requirements that had grown up over the previous century. Prior to its enactment, efforts had been made to pass federal laws instituting a national “postcard” registration form and to encourage states to adopt “motor voter” laws — that is, laws allowing citizens to register when they got their driver’s licenses.

The first attempt to pass the NVRA failed in 1992, when Congress passed the law but President George H.W. Bush vetoed it. Just one year later, though, Congress passed a similar measure that was signed into law in 1993 by President Bill Clinton. The NVRA contained the following major provisions:

- States were required to allow voter registration by mail.

- States were required to offer voters the opportunity to register to vote simultaneously when applying for a driver’s license, and were also required to offer registration at public assistance agencies.

- States were not allowed to remove voters from the rolls solely for non-voting. Voters were allowed to be removed only if they requested it or if they died, moved out of jurisdiction, or were removed because of a felony conviction or mental incapacity.

Although the NVRA prohibited the removal of voters from the rolls simply for non-voting, it did allow states to use non-voting as a trigger to inquire whether a non-voter had moved from the jurisdiction without notifying local election officials. In particular, a state can remove someone from the rolls if it sends a notice to a non-voter and the non-voter fails to respond (or vote) within the next two federal elections.

The NVRA exempted a few states from these requirements, if they — at the time the NVRA passed — either didn’t have a voter registration requirement at all or allowed voters to register on Election Day at the polls. Later, this exemption was also extended to two additional states that passed legislation allowing Election Day registration soon after the NVRA was enacted. As a result, six states are exempt from the NVRA: Idaho, Minnesota, New Hampshire, North Dakota, Wisconsin, and Wyoming.

How many voters are registered?

The Election Assistance Commission’s 2016 report on the implementation of the NVRA stated that there were 211.1 million registered voters in the 50 states plus the District of Columbia. With an estimated voting-eligible population of 230.6 million, this suggests that 92% of eligible voters are registered and on the voting rolls.

Unfortunately, getting an accurate estimate of registered voters is not quite that simple. These registration statistics are undoubtedly an overestimate due to the persistence of deadwood on the rolls. Precisely how much deadwood persists is unknown, and the subject of intense research and public debate. Research by Stephen Ansolabehere and Eitan Hersh, which relies on data collected by a major voter list vendor, indicates that around 10% of the names on voter rolls nationwide are deadwood. Even that amount, though, is a very broad estimate, because deadwood varies across states — and within states across time, depending on when they perform major list maintenance (“purging”) efforts.

Another way to estimate the amount of deadwood is to examine the number of inactive voters in the states that distinguish between active and inactive voters. (In general, states that use the “inactive” voter category will move a registered voter to inactive status when they have reason to believe the voter has moved or died, but have not yet received definitive confirmation.) In 2016, among the states that use the inactive status, 10.7% of registrants were inactive, ranging from 0.5% in Maine to 19.4% in Arkansas. Taking the inactive percentage as an estimate of the amount of deadwood on the voter rolls, this would suggest that the actual voter registration rate nationwide is closer to 82% of the eligible electorate.

An alternative approach to estimating the number of people actually registered in each state is to rely on answers to survey questions that ask whether respondents are registered to vote. This approach is used by the Elections Performance Index, justified in part by analysis performed by Barry C. Burden in the book The Measure of American Elections. Burden notes that survey-based measures of registration rates are correlated with the rates reported by states using official data, but that survey-based measurements are generally less extreme than the state-reported rates.

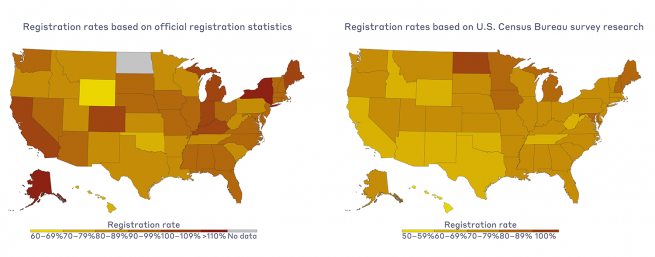

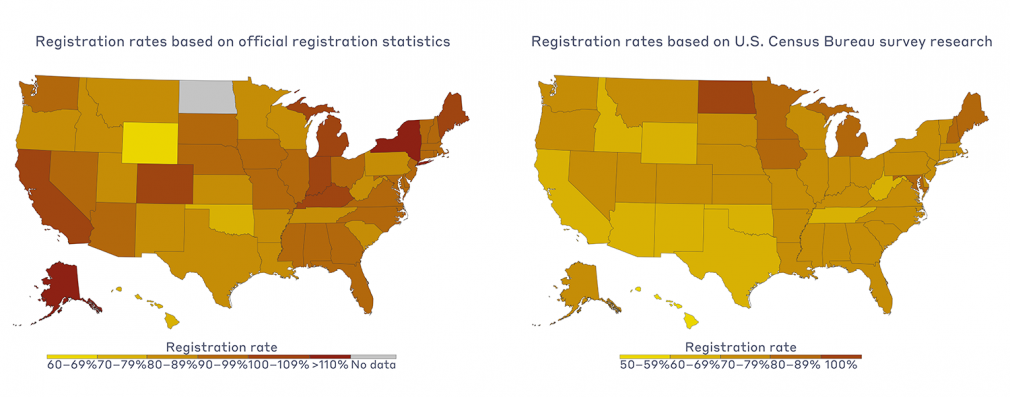

The two maps below illustrate the reported voter registration rates in 2016 using two methods. The first map shows registration rates based on the officially reported number of registered voters in each state. The second map relies on responses to the 2016 Voting and Registration Supplement of the Current Population Survey, conducted by the U.S. Census.

The first thing that is apparent in the first map is that there are nine states with more registered voters than the estimated citizen voting-age population. This is clear evidence of significant deadwood on the rolls of these states, but it does not mean that significant deadwood doesn’t exist on states with official registration rates less than 100%.

By design, no state in the second map has registration rates exceeding 100%. In this map, we can see a clearer regional pattern, in which the lowest voter registration rates are generally in the Southwest and the highest generally in the northern tier of states.

New developments

In recent years, states have been working to develop and adopt new approaches to voter registration. These movements have been spawned by a mix of citizen activism aimed at mobilizing new voters, public officials’ concern about low turnout rates, and a desire to take advantage of computer technologies to decrease the costs of of registering voters while increasing the accuracy of voter lists at the same time.

Learn more about new registration methods at the National Conference of State Legislatures.

Learn more about new registration methods at the National Conference of State Legislatures.

The first new development is a resurgence of interest in Election Day registration (which is sometimes called same-day registration). Since 2010, eight states have passed same-day registration laws, doubling the number of states with such legislation. As of the 2018 election, 16 stateswill also allow their citizens to register and vote at the same time. Two of these states, Maryland and North Carolina, allow citizens to register and vote only during the early voting period; the rest allow registration and voting on Election Day itself.

The second new development is online voter registration (OVR). As the name implies, online voter registration allows citizens to register to vote online. To do so, a voter generally fills out a registration form electronically, which is then verified by voting officials at the state level. In most cases, voters must already have a driver’s license or other form of state identification in order to register using OVR. Arizona was the first state to adopt OVR, in 2002, and its experience with the system — which lowered the state’s costs and decreased data errors — has spurred a steady increase in the number of states adopting OVR in their own election processes. During the 2015–2016 election cycle, 17% of all new nationwide registrations were received online, which made it the second-most-common source of new voter registrations after departments of motor vehicles.

The final notable recent development in voter registration is automatic (or automated) voter registration (AVR). AVR goes one step further than the traditional “motor voter” system, in which citizens are offered the opportunity to register when they get a driver’s license. Instead of this more traditional “opt-in” approach, AVR is an “opt-out” system: holders of driver’s licenses are automatically registered to vote unless they explicitly ask to be taken off the voter list. AVR was first enacted by Oregon in 2015, but since then, another eight states have adopted it (although only Alaska and Colorado have actually begun implementation).

The first comprehensive study of the effects of AVR in Oregon, published by the Center for American Progress (CAP), revealed that new voters who registered through AVR were younger, more racially diverse, and less likely to come from urban areas than traditional registrants. No published study has yet to document whether AVR increased voter turnout in Oregon. However, based on the statistics published in the CAP report, it appears that instituting AVR increased Oregon’s turnout in the 2016 election by between 1.5 and 3.5 percentage points.