Poll Worker Decision Making at the American Ballot Box

The MIT Election Data and Science Lab helps highlight new research and interesting ideas in election science, and is a proud co-sponsor of the Election Sciences, Reform, & Administration Conference (ESRA).

Mara Suttman-Lea recently presented a paper at the 2019 ESRA conference entitled, “Poll Worker Decision Making at the American Ballot Box.” Here, she summarizes her analysis from that paper.

Depending on where they live, voters in the United States are asked to provide a range of different information — from writing their signature on an application to providing a photo identification — in order to confirm their identity and eligibility to cast a ballot.

While recent research has been focused on the impact of variation in these requirements for access to voting — most notably of laws requiring citizens to show photo identification — far less attention has been paid to how laws that are passed at the state level for verifying voter eligibility are actually implemented by their most direct arbiters: poll workers. Poll workers have substantial authority in determining whether citizens have provided adequate information to prove their eligibility to vote. As one poll worker from the city of Chicago put it:

“I see myself as a bridge between the people and the ones representing us, because without poll workers you can’t have a proper election… Ultimately we are the ones who decide who gets to vote and who doesn’t.”

Research

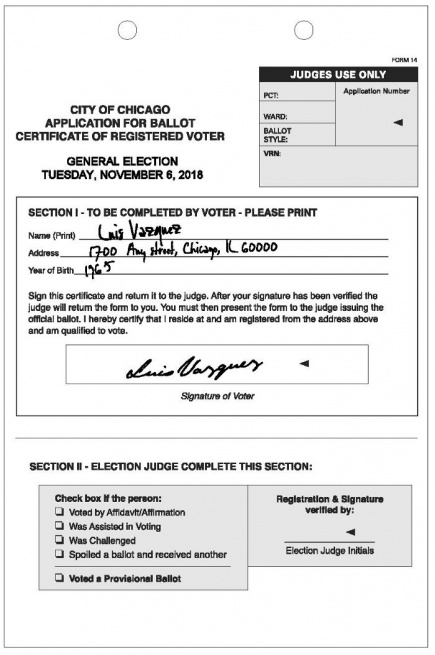

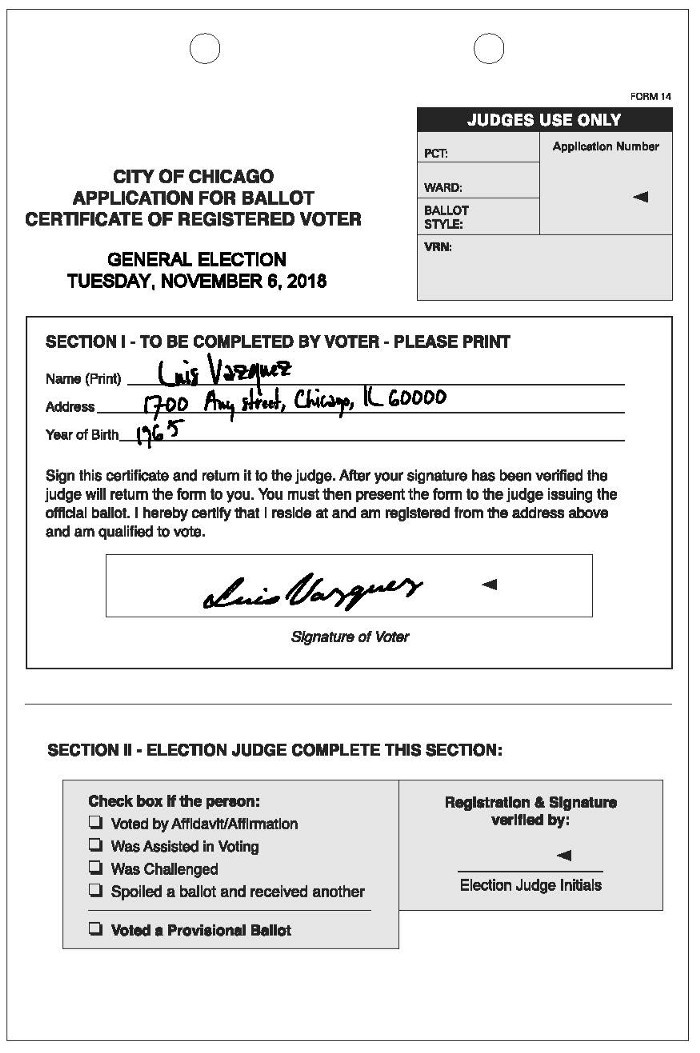

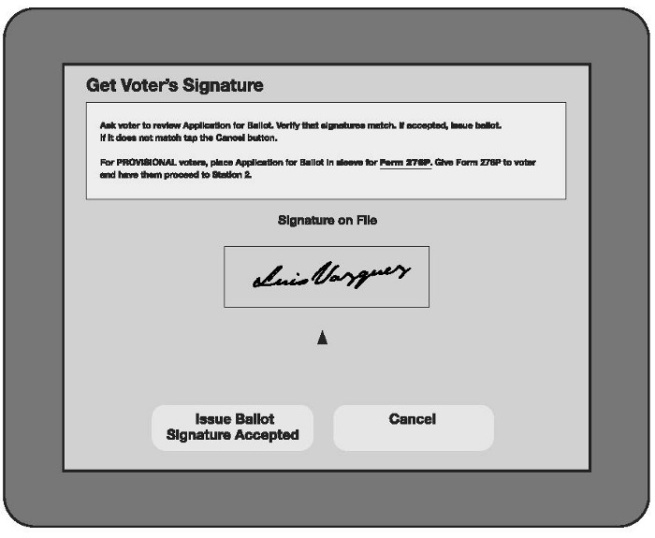

My research looks at how poll workers make decisions about voter eligibility. I draw from 26 in-depth interviews with poll workers from Chicago, Illinois. As illustrated in the figure below, a key part of the process of verifying voter eligibility in Chicago is to have voters provide a signature on an application for ballot that is then compared with a signature in an electronic poll book. If a poll worker determines a signature doesn’t sufficiently match, there are a number of steps they can take, including verifying the signature with a fellow poll worker or asking the voter for other identifying information.

Local election officials rely on poll workers to ensure elections are run smoothly, and have to trust that their poll workers will properly implement the election laws they are tasked with enforcing. Ultimately, however, the high level of delegation to poll workers and lack of oversight creates the potential for significant problems in the polling place. Furthermore, poll workers may be uniquely subject to the shirking and sabotaging of policies — whether purposeful or unintentional. By virtue of their temporary status, they are not likely to be a part of the organizational culture of higher levels of election administration. Unlike career bureaucrats, poll workers are less likely to have a shared set of norms or sense of conformity, and are not subject to consistent and direct oversight. My research examines how these concerns play out in the actual considerations made by poll workers when making decisions.

In my interviews, I asked poll workers questions about what they look for when confirming voter eligibility, how they proceed when they are not certain the information provided by a voter is adequate, and what kind of training they get on confirming voter eligibility by signature matching. Respondents revealed a range of considerations. Not surprisingly, many encountered signatures that had changed over time, but there were different responses over what constituted mismatching signatures and what to do with them.

A pollworker named Dave, for example, said he would look for some part of the signature that looked similar to what was on the electronic poll book, “like a little curve here or a curve there, crossing a T and dotting an I.” He said he never ran across an instance where he challenged a voter. Alex, on the other hand, said if the signature looked completely different, “something is enough amiss that this isn’t serving as a confirmation of anything to me. At that moment, I will say, ‘look sir, you can see this… It is so far from what it used to be. I just have to ask for ID.’”

One common — and surprising — theme that came up in my interviews was the suggestion that working in the same precinct from election to election allowed poll workers to develop a sense of familiarity with the voters they saw, which made confirming their identity easier. This was especially helpful if poll workers were assigned to precincts in their home neighborhood. Many also suggested that being able to work with the same poll workers from election to election allowed them to develop a sense of camaraderie with their co-workers that felt more like a long-term working relationship rather than a temporary experience limited to Election Day.

While these findings raise concerns about situations where poll workers have substantial discretion in their verification of voter eligibility — particularly in states where they are examining information as capricious as signatures — they also offer some insight on potential solutions to the problems inherent in the “human element” of elections. The idea that working in the same precinct from time to time (especially if it is near where one lives) makes the process of verifying voter eligibility easier deserves closer empirical scrutiny. When I asked one poll worker, Nicholas, what he felt the most positive aspects of his experience working as a poll worker were, he responded that he felt the “whole experience of doing it is rewarding for the soul. I think there is a personal benefit, but also a benefit for the community because you are not going to try to do wrong to the people that you know better than a stranger.” This suggests there may be a pro-social motivation to ensure positive experiences for the voters poll workers see from election to election, especially if they are one’s neighbors.

While having poll workers serve in the same precinct in their home neighborhood from election to election is certainly not a panacea, if implemented in an intentional way, over time it may allow for a group of otherwise temporary, volunteer-like workers to develop informal organizational norms and systems of accountability. At the same time, it is important to acknowledge that familiarity with voters may also lead to a willingness to overlook important steps in the voter identification process, and could exacerbate the principle-agent problem faced by election administrators if poll workers develop systems that deviate from what is laid out in poll worker training.