The Representational Consequences of Electronic Voting Reform

Evidence from Argentina

The MIT Election Data and Science Lab helps highlight new research and interesting ideas in election science, and is a proud co-sponsor of the Election Sciences, Reform, & Administration Conference (ESRA).

Our post today was written by Santiago Alles, Tiffany Barnes, and Carolina Tchintian, based on their paper presented at the 2021 ESRA Conference. The information and opinions expressed in this column represent their own research, and do not necessarily represent the opinions of the MIT Election Lab or MIT.

Do voting instruments affect the fate of parties and candidates?

Some voting procedures have been the center of heated political disputes—e.g., changes in voters’ registration, in the requirements of voters’ IDs, or in the use of mail-in voting. Instead, the design of ballots triggers political controversies less frequently. Despite that ballot structures vary dramatically across and within countries, scholars studying electoral institutions have scarcely considered how they influence the way voters translate their preferences into votes and how elites develop campaign strategies reacting to different ballot designs.

Among the wide variety of ways to cast a vote, electronic voting devices have been adopted in the last couple of decades in an attempt to improve electoral processes by offering more user-friendly procedures for voters, bolstering confidence in elections and automatizing vote tallying. Latin American democracies have emerged as a very active laboratory of innovation in voting procedures, and they offer multiple examples of the use of electronic voting: while Brazil provides by far the largest implementation in the region, it was also adopted or piloted in national elections (in Venezuela and Paraguay), as well as in local elections (in Argentina, Perú, Ecuador, and México).

Throughout this piece, we present evidence that, despite other potential effects in terms of efficiency, transparency and usability, ballot forms (in general) and electronic voting (in particular) shape the influence of candidate’s attributes on election outcomes, focusing on two specific aspects, experience and gender.

The Ballots

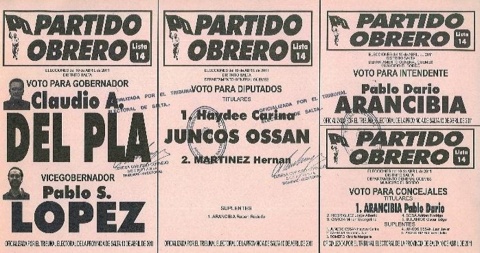

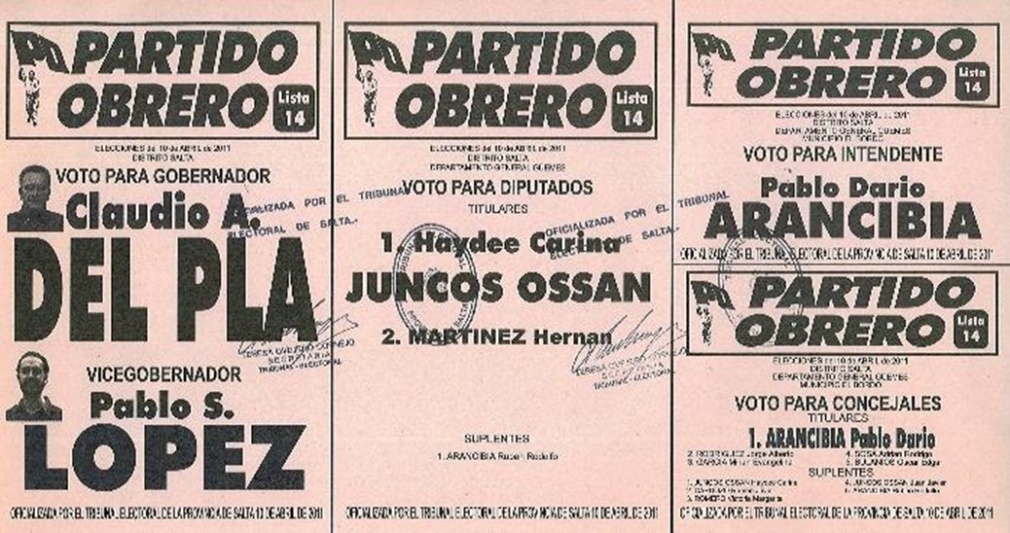

Two Examples of Partisan Paper Ballots from provincial and national elections in Argentina. Left: Provincial election: Salta, 2011. Right: National election: Buenos Aires, 2019.

Two Examples of Partisan Paper Ballots from provincial and national elections in Argentina. Left: Provincial election: Salta, 2011. Right: National election: Buenos Aires, 2019.

Partisan paper ballots are the most common voting procedure in Argentina. These ballots are used in the election of every national office, and despite recent innovations in some provinces, they are still the usual voting procedure in subnational elections as well.

When using these ballots, candidates of each party are presented separately. All the candidates are displayed in a single piece of paper, from the higher office on the left, to the lower office on the right. If you look at the left-hand side figure, you will see an example from the 2011 election in Salta: candidates running for governor and lieutenant governor are followed by candidates for the provincial-level lower House, who are followed by candidates for local-level offices.

Though straight-ticket voting is the easiest choice, voters can split their vote across races; to do so, they need to physically separate (i.e., cut or tear) the ballot.

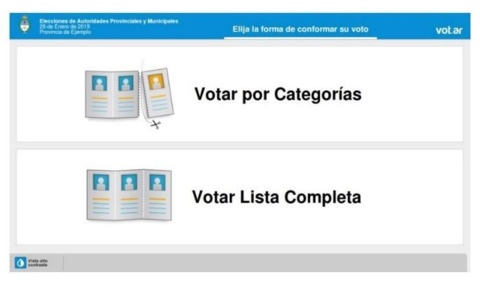

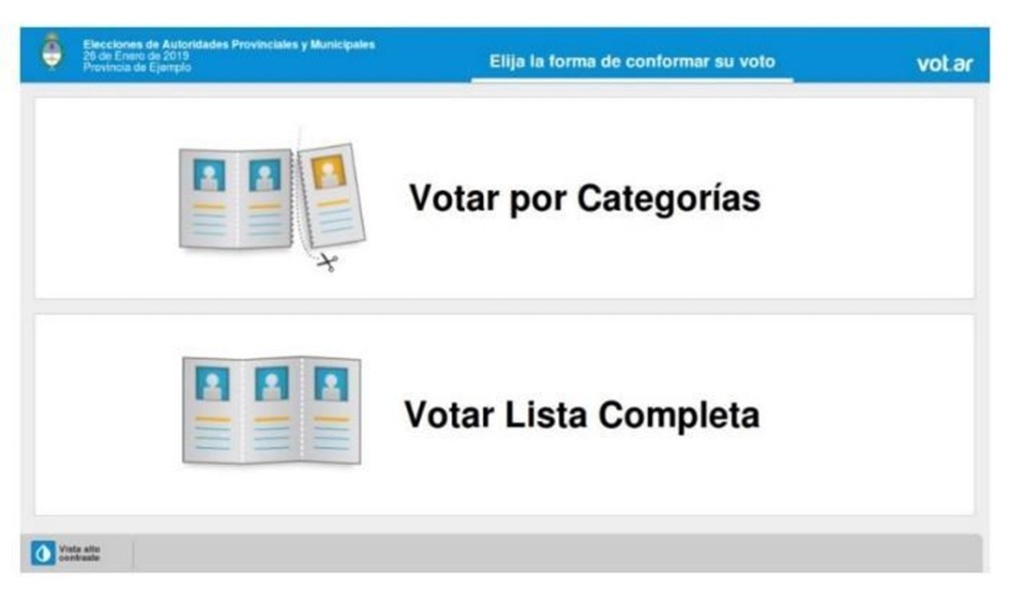

Demonstration of Electronic Voting in Salta from the dissemination materials of the electoral authority. Left: Voting by party v. Voting by office. Right: Candidates by office.

Demonstration of Electronic Voting in Salta from the dissemination materials of the electoral authority. Left: Voting by party v. Voting by office. Right: Candidates by office.

Paper ballots were replaced by the adoption of electronic voting in Salta by the beginning of 2010s.

The electronic devices lay out electoral options differently. First, as it is presented on the left-hand side figure, the device allows voters to choose how candidates will be sorted, either by party or by office. If the voter selects the see the options by party, she can cast a straight-ticket vote by selecting her preferred party in a single step. If the voter instead selects to see the options by office, the device presents candidates race by race, as it is shown in the right-hand side figure; and she will select the party she prefers for each office, one office at a time.

This is theoretically important because allowing the possibility of going race by race, the electronic devices facilitate split-ticket voting, and doing so, they are expected to weaken party coattails and to strengthen the value of candidate attributes in down-ballot races.

To show the effect of the ballot form on election outcomes, we leverage a cross-sectional design, based on 240 mayoral elections in the Province of Salta (Argentina), across four election cycles (from 2007 to 2019), comprising 1,185 candidate-level observations.

The Influence of Political Experience

Does ballot form shape the influence of a candidate's experience on election outcomes? If the ballot weakens straight-ticket voting and party attachment are less influential, it is expected that candidates will be more likely to depend on their personal reputation. Political experience comes with name recognition and political resources such as party networks, all very helpful to run for an elected office.

We focus on two forms of experience: whether a candidate was the incumbent mayor, and whether a candidate was a (current or former) provincial legislator. There are many other forms of political experience, but candidates who have held higher positions—e.g., governors or national legislators—very rarely seek mayor’s office. Importantly, name recognition may also come from non-political careers, such as being a successful businessperson or a media personality, but it is virtually impossible to track down systematic information on candidates competing for local-level elections over a decade ago in rural Salta. So, we rely on official government records that allow us to systematically account for whether candidates previously held an elected office.

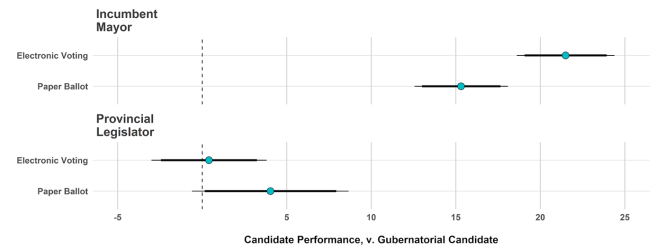

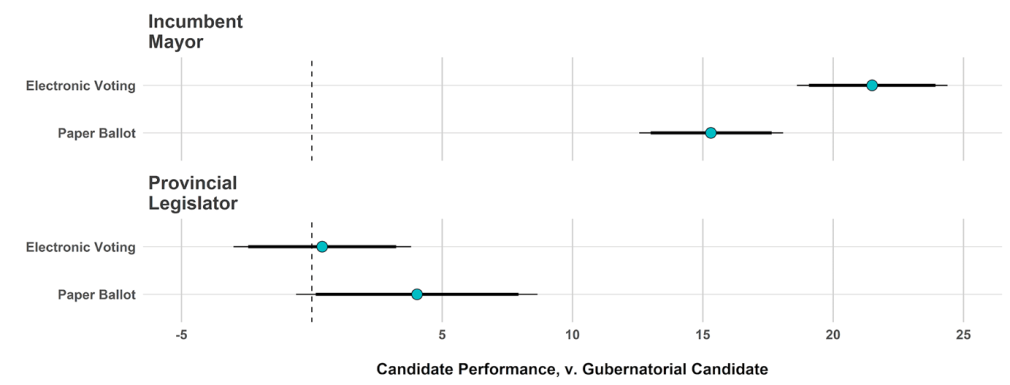

Expected Mayoral Candidate’s Electoral Performance by candidate’s experience.

The electoral performance of a mayoral candidate is measured by comparing it to the candidate at the top of the ticket. In the figure, the baseline is the performance of the gubernatorial candidate: when a mayoral candidate gets the same votes, the value is zero; and when a mayoral candidate outperforms the gubernatorial candidate, values are positive.

Overall, incumbent mayors do great. Incumbents outperform the average candidate by about 30 percentage points, and they outperform their own gubernatorial candidate as well. More importantly, as it is shown in the upper panel, incumbent mayors in elections using electronic devices are doing 6 points better than other incumbents competing in elections still using paper ballots, and this gap is statistically significant. Instead, as it is shown in the lower panel, provincial legislators do not benefit from electronic devices.

That is—not all the forms of experience are equally important. Our results show that electronic devices favor candidates with stronger attributes.

The Influence of Gender

Next, we consider whether ballot form structures the influence of candidate’s gender on election outcomes. Candidates’ sex is a piece of information that voters use to make their minds. There is significant evidence that women candidates are held to higher standards than men. A ballot form weakening straight-ticket voting is expected to comparatively hurt women in down-ballot races.

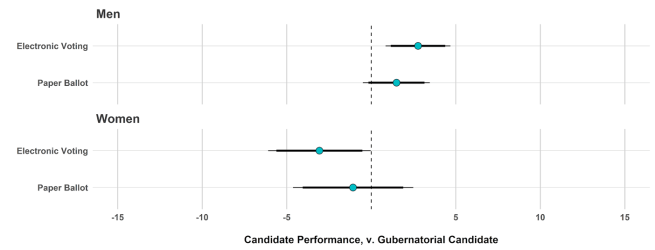

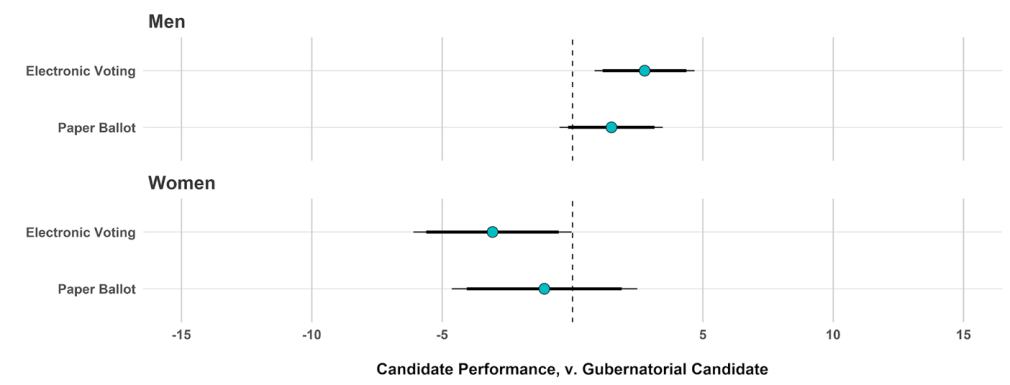

Expected Mayoral Candidate’s Electoral Performance by candidate’s gender.

The measure of electoral performance is the same as before, a comparison between the performance of mayoral and gubernatorial candidates, but now we are looking at the gender of the mayoral candidate.

First, there are no differences between ballot forms within gender groups—i.e., women competing on paper ballots compared to women competing on electronic ballots, nor are there differences between men competing on the two ballot types. This is clear when you look at each panel. Women candidates do not perform better or worse under paper ballots than those women competing on electronic ballots. The same is true for men.

However, there are some differences between gender groups. In elections using electronic devices, men candidates are more likely than women candidates to outperform the gubernatorial candidate at the top of the ballot. Women candidates, by contrast, are typically worse-off on electronic ballots than the candidate at the top of their ticket. But, in elections using paper ballots, the performance of candidates is not linked to their sex.

Overall, results on gender are in the expected direction, but they are not very strong—this might be due to the limited number of women in the pool of mayoral candidates.

Conclusions

The ballot form can shape the influence of a candidate's attributes on election outcomes. Our results show however that some types of candidates are in a better position to exploit these opportunities. Personal attributes are, of course, not limited to experience or gender; many other individual characteristics may raise the saliency of candidates or signal personal traits that voters consider valuable. Some ballot forms may boost the influence of personal attributes on election outcomes.

Ballot designs may help voters to single out candidates across races—a ballot form that helps voters to make discrete choices, makes it easier to hold politicians accountable. Voters are in a better position to penalize corrupt politicians or vote out unsuccessful governments when they can single them out.

However, a ballot reform may present more complex trade-offs for democratic competition. By heightening a candidate's personal attributes, a ballot form can reinforce the position of established political elites, undermining the opportunities of newcomers—e.g., challengers and women.

And they may introduce difficult challenges for parties. A larger influence of candidates’ personal attributes may lead to a larger personalization of elections too—for example, creating new opportunities for political outsiders. More broadly, larger personalization may reshape the relationship between candidates and parties, empowering candidates, and affecting party discipline and cohesion. Weaker parties may have significant implications for campaigns, and once in office, for the policy-making process.