The Shifting Standards of Signature Matching in Georgia

The MIT Election Data and Science Lab helps highlight new research and interesting ideas in election science, and is a proud co-sponsor of the Election Sciences, Reform, & Administration Conference (ESRA).

Our post today was written by Clint Smith and Delaney Gomen, based on their presentation at the 2021 ESRA Conference. The information and opinions expressed in this column represent their own research, and do not necessarily represent the opinions of the MIT Election Lab or MIT.

While most Americans have traditionally cast their ballots in person, the arrival of the COVID-19 pandemic and increased concerns over public health led to a drastic expansion of voting by mail during the 2020 general election.

In fact, Pew reports that 46% of voters said they cast their ballot by mail in 2020, which is up from 20.9% in 2016. Given its increased use across the country, public scrutiny has recently focused on the mechanics of absentee voting. We examine one aspect of these mechanics: invalid signature rejections or those absentee ballots that are rejected because the signature on the ballot doesn’t appear to match the one on file.

While signature matching hasn’t received much attention in the past, this changed when then-President Trump tweeted claims of a low number of absentee ballots rejected in Georgia for invalid signatures. Trump’s implication was clearly that local election officials weren’t sufficiently scrutinizing absentee ballots, opening the door to potential fraud. Even though Georgia’s Secretary of State demonstrated that 2020 rejection rates were on par with recent elections, and the state’s own post-election signature audit found no evidence of fraud, this rhetoric still permeated the media landscape.

Given that there was another highly publicized election in Georgia only a few months following the general election, we took this opportunity to see if there were any differences in the rejection behavior of local administrators after Trump’s interjection. Were there changes in the way that elections were administered on the ground in Georgia?

Invalid signature rejections in Georgia

While absentee ballots may be rejected for invalid signatures, voters are often given the ability to cure those ballots. In Georgia, specifically, voters are notified that their ballot was rejected for invalid signature and given up to three days after the polls close to submit an affidavit to the Board of Registrars or absentee ballot clerk confirming that the ballot was submitted by the registered elector (O.C.G.A. §21-2-386).

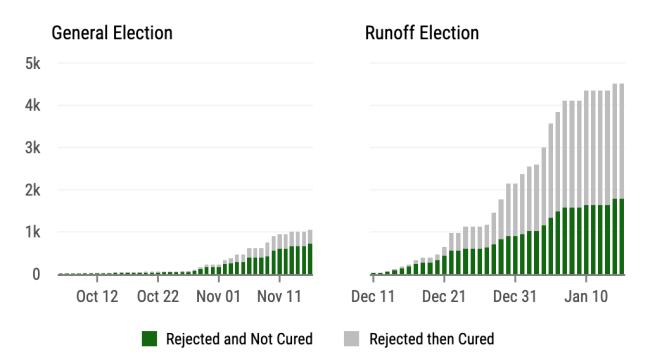

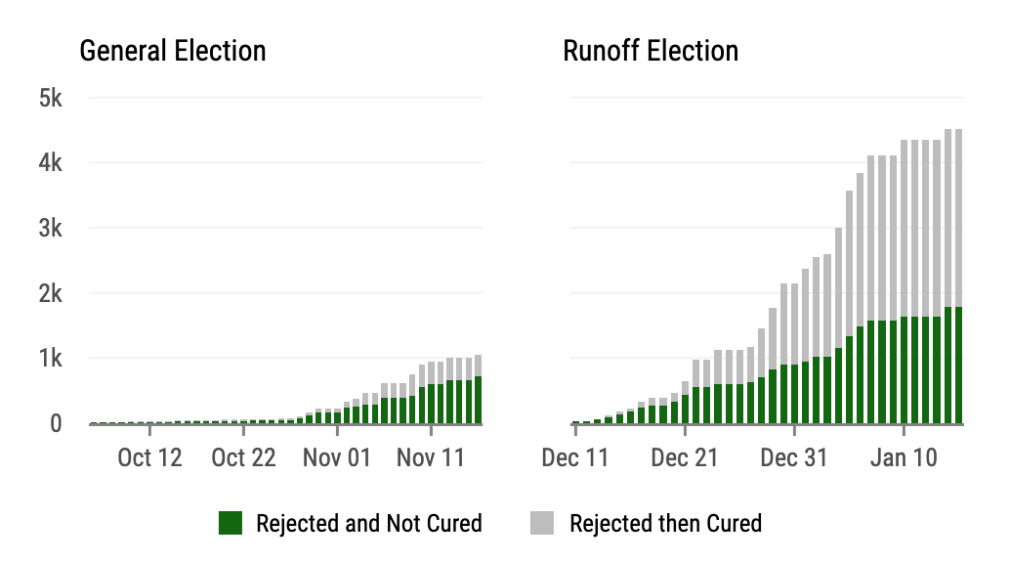

These ballot cures then represent confirmed instances of erroneous rejections. If you were to simply examine the number of ballots rejected at the final tally, as is common, you would miss all the previously rejected ballots that were subsequently accepted after a successful cure. To get the number of both rejections and cures we rely on data from VoteShield.

Because VoteShield's base technology allows us to track changes over time to individual records in a file, we can see those ballot cures that would otherwise be invisible when looking at any single instance of the data. When a ballot is received and processed, we can see whether it was rejected for an invalid signature in the ballot status field. Identifying cures is simply a matter of regularly reviewing these rejected ballots for changes in their statuses to “accepted” in subsequent instances of the absentee ballot file.

Invalid Signature Rejections in the 2020 General and 2021 Runoff Elections.

In the Georgia runoff for the U.S. Senate, where there were about 350,000 fewer absentee votes, there was a four-fold increase in ballots rejected for an invalid signature. We also saw the cure rate increase from 32.4% in the general election to 60.6% in the runoff, suggesting that the surge in rejections was due to higher levels of incorrectly rejected ballots. Finally, while the increase is noticeable for final rejections alone (an increase of more than 100%), only when we consider the cures do we see the true magnitude of the change in rejection behavior (an increase of more than 300%).

A shift in voter profiles for invalid signature

Not only did we find an increase in invalid signature rejections, but we also see that the profiles of voters rejected changed substantially. The scant academic research on absentee ballot rejections suggests that younger, less experienced, and/or minority voters are more likely to be rejected (see here and here). This research, however, relates to different kinds of rejections (e.g., rejections for missing information or those received past the deadline) and explicitly excludes those for signature mismatches.

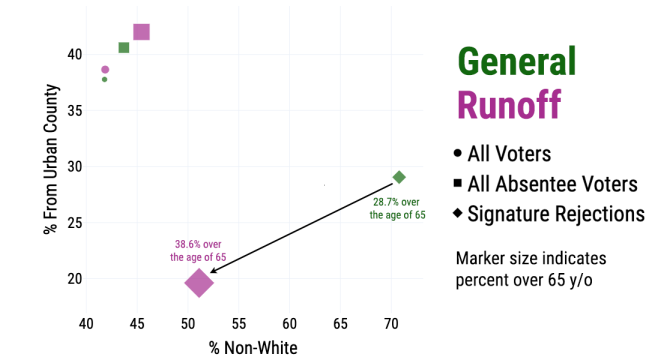

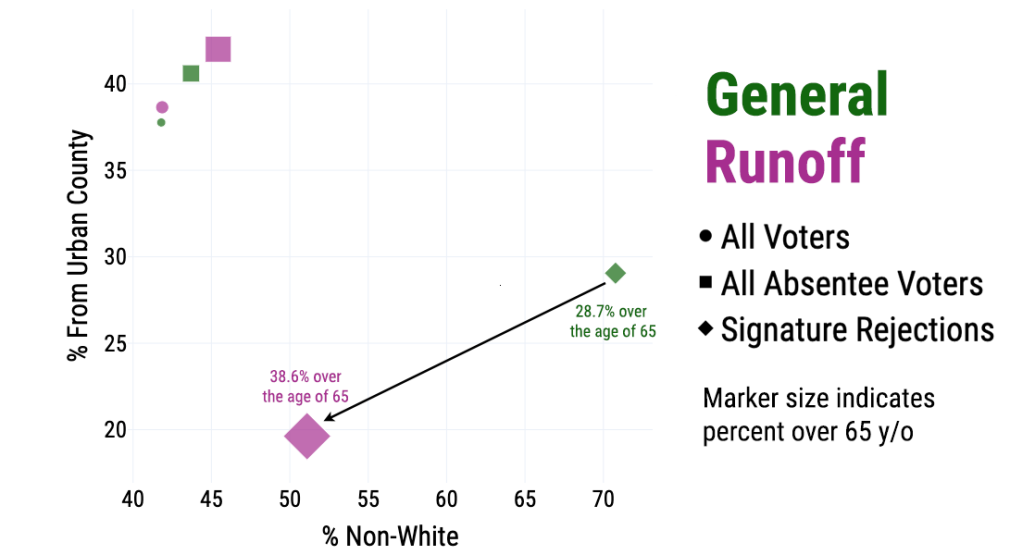

Rejections specifically for invalid signatures may reveal a different pattern. For instance, they may occur more commonly among older voters than other types of rejections due to the potential for signatures to change over time. We make no claims about the expected composition of the rejected voters in the 2020 general election. Rather, we focus on the changes in rejection behavior between the 2020 general election and the 2021 Senate runoff.

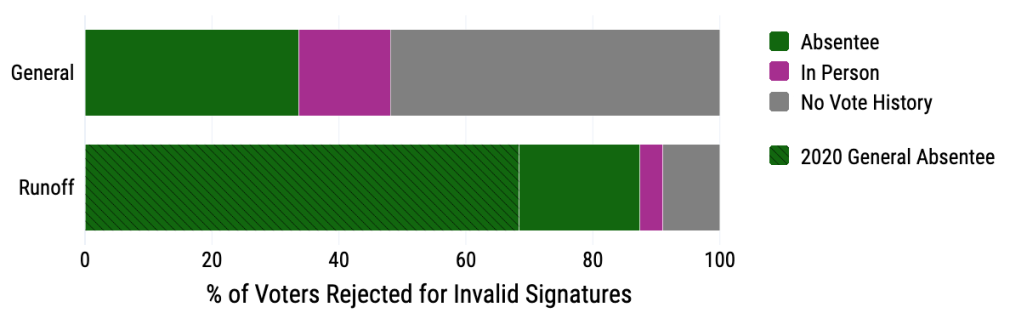

We compare different populations of Georgia voters in terms of their demographic makeup on three key dimensions: race, geographic location, and age. What we find is that the population of “all voters” and “all absentee voters” didn’t change too much between the general and runoff elections. If we examine the population of voters rejected for invalid signatures, however, we see a drastic shift in demographic profiles. Compared to the general, voters who were rejected for mismatching signatures in the runoff were, on average, either more likely to be 65 years of age or older, non-white, or from an urban county.

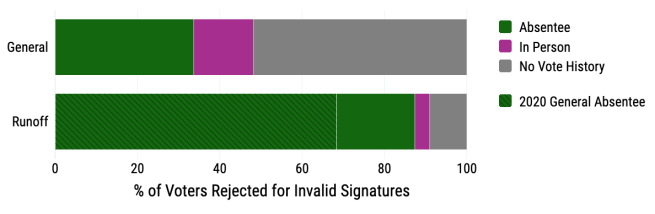

In addition to its size and the altered voter profiles, the group of invalid signature rejections in the runoff is also different with respect to voting experience. Rejected voters in November tended to have very little experience with voting; more than half of them had never cast a ballot before. Yet, 91% of rejected voters in the runoff had prior experience. Furthermore, more than 68% of the rejected voters in the runoff successfully cast an absentee ballot less than two months prior in the general election. In all, the runoff rejected voters were much more experienced with voting than the general election rejected voters and not all this difference is attributable solely to 2020 participation. On average, rejected voters in the general election participated in 1.3 previous elections, while the rejections in the runoff on average participated in 2.7 previous elections.

Conclusions

Although we can’t attribute the increase in invalid signature rejections to Trump’s comments with scientific certainty, we can say that the increase in rejections was not likely caused by a corresponding increase in invalid signatures. Unlike in the general where only 32.5% of invalid signature rejections were cured, in the runoff more than 60% were cured. These cures account for more than 69% of the total increase in rejections. Assuming the state reports these ballot statuses accurately, administrators in the runoff were much more likely to reject a valid ballot for signature matching than in the general. Furthermore, almost three-quarters of the rejections in the runoff successfully voted by mail in the general election just over two months prior. It seems unlikely that signatures would change so drastically as to be unrecognizable in such a short period for so many voters.

Since it’s doubtful that all rejected voters took the opportunity to cure their ballots, the change to a stricter signature matching standard in the runoff likely led to the cancellation of some legitimate ballots that otherwise would have been counted. While there weren’t enough of these ballots to affect the outcome of state-wide races in any way, they could matter in local races.

Despite SB 202 removing signature matching in Georgia earlier this year, voter signatures remain a common means of verifying voter identities on mail and absentee ballots across the states. Although some jurisdictions impose standards meant to remove the subjective elements of this method, many others don’t. Furthermore, in the wake of "The Big Lie," states without signature matching are moving to implement it. In Idaho, for example, HB 290 imposes new signature matching requirements, without addressing the issues of subjectivity identified above. While these types of requirements may not shift the outcomes of state or national elections, they will certainly lead to the cancelling of ballots for some eligible voters and undoubtedly contribute to the permeating lack of faith in our electoral process.