Texas High Schools’ Noncompliance with Voter Registration Requirements

The MIT Election Data and Science Lab helps highlight new research and interesting ideas in election science, and is a proud co-sponsor of the Election Sciences, Reform, & Administration Conference (ESRA).

Our post today was written by members of the University of Houston Election Lab: Professor Brandon Rottinghaus, Assistant Professor Jeronimo Cortina, Ph.D. students Naomi Nubin and Amanda Austin, and incoming graduate student Syed Naqvi. It is based on their research presented at the 2021 ESRA Conference. The information and opinions expressed in this column represent their own research, and do not necessarily represent the opinions of the MIT Election Lab or MIT.

Though Texas laws require public high schools to offer voter registration to eligible students twice a year, research by the University of Houston Election Lab finds that only one quarter of high schools in the state comply with this requirement.

This noncompliance has the potential for widespread and longstanding negative effects on turnout as every year about 300,000 Texas high school students become eligible to vote but most are not habituated to do so at the outset of their eligibility. Downstream consequences can include voter turnout that falls below the national average and underrepresentation of youth policy interests. To better understand why this phenomenon is so ubiquitous in Texas we explored various geographic and socioeconomic factors at the school level to determine which are most closely related to legal noncompliance.

Youth Voter Habituation

High school voter registration requirements, such as those in Texas, can lower the burden of casting a ballot for first-time voters. The “cost” of voting - especially the time and effort it takes to vote – can impact voter turnout. Census data finds being “too busy” tops the list of reasons for voters to not vote. Scholars have found that the structure of the voting process - including the days before Election Day required to register, vote by mail, or vote early - have been shown to be important at affecting aggregate level turnout. Voting itself is habit-forming, reinforced by repetition, including the introductory process of registration. This habituation is especially critical for young and first-time voters who are less often socialized to voting. Schools, which already serve as a primary socialization agent for many young people, can set this habituation process in motion.

Schools may provide a particularly critical link to voting for minority populations who have historically lacked access to the ballot. Intergenerational transmission of information about voting processes may occur less frequently among groups who have been historically marginalized from voting, such as racial and ethnic minorities, women, and new immigrants to the U.S. Failure to bridge this generation gap can result in a perpetuation of marginalization of these groups, as lower voter turnout by sex, race, class, and/or ethnicity can lead to a reduction in political representation and its resulting distributional benefits.

When schools engage in inclusive efforts to encourage voting assistance, they can increase turnout and representation of their communities’ interests. Pairing high school voter registration efforts with civic education courses can prove particularly efficacious in enhancing political engagement of historically marginalized communities. Civic education intervention has been shown to close racial gaps in political knowledge, interest, and voting. Scholars find that exposing youth to political information positively affects their sense of confidence and boosts confidence when casting a ballot. Learning how to register to vote is a critical component of the political knowledge an engaged citizenry must acquire. High schools have the potential to play an important role in the transmission of this knowledge by empowering their students with the tools and knowledge necessary to participate in public life.

Texas Voter Registration Requirements

In Texas, voters must be registered in the county in which they reside at least 60 days before the election. Physical voter registration forms are available at most local Department of Motor Vehicles locations, libraries, and post offices. Alternatively, a form can be requested online, which is then downloaded online or is mailed to a prospective registrant (Texas does not allow people to fully register online but they use the Internet to facilitate sending the form). Voter registration forms must be filled out and mailed to the county in which a person lives. The county official responsible is either the county Tax Assessor Collector or a county Election Administrator. To be eligible to vote in the state, a person must be a U.S. citizen, a resident of the county in which the application is made, at least 18 years old on Election Day, and not finally convicted of a felony.

Due to low voter turnout, especially among younger voters, Texas in 1984 expanded voter registration laws to require high schools to register their students to vote (Texas GOV. Code § 13.031(B); Texas Election Code § 13.046). The law requires public high schools to provide opportunities to register to vote to eligible students aged 17½ years or older twice a year. The principal of each Texas high school, or the principal’s designee, is designated by law as the high school deputy registrar (HSDR). The HSDR must offer voter registration applications to eligible students at least twice per school year, along with a notice explaining how the students may deliver the applications. Students may choose to return voter registration forms to the HSDR; then, the HSDR must review the applications for completeness, give assistance upon request, and collect them for delivery to the county voter registrar. Alternatively, students may give their voter registration form to a Volunteer Deputy Registrar (VDR) to turn into the county voter registrar.

Administrative Barriers to Compliance

Barriers to compliance with this law occur on two levels: that of the state and that of the schools. Though our research focuses on the level of high schools, it is important to note that administrative barriers on the state level may also hinder compliance. Of foremost concern is the fact that Texas high schools must twice yearly request voter registration forms from the Texas Secretary of State, rather than an automatic statewide distribution of forms to school officials. Further, the Texas Secretary of State does not maintain an updated contact list of school officials to contact with compliance instructions, nor does the Secretary of State track or report high schools’ legal compliance or engage in any form of legal enforcement, though if a school requested voter registration forms from the Texas Secretary of State, these records are kept as part of the public record.

There is a clear a tradeoff in the administrative burden between schools and the state government. The present system places this burden upon schools because the cost of compliance has been decentralized to the local level. This decentralization may penalize marginalized communities who lack financial and informational resources to adequately comply. It may also penalize Texas taxpayers who must pay for the duplicate cost of compliance across schools rather than a single, streamlined cost at the state level. Texans may further lose out by the lack of voice of so many young voters in the political arena.

Empirical Strategy

We gather data from four sources: the Texas Civil Rights Project, an original survey fielded by the University of Houston Election Lab, and the National Center for Education Statistics, and the Texas Education Agency. Data from the Texas Civil Rights Project (TCRP) on Texas public high schools’ legal compliance with high school voter registration requirements are either reported by high schools through a survey by TCRP or identified through public records requests from the Texas Secretary of State. TCRP surveys to Texas public high schools were fielded in February 2017, August 2017, and February 2018. The University of Houston Election Lab followed up with schools in February 2020 with a separate survey to determine compliance. Compliance at any time in this window is coded as compliant (1, otherwise 0).

We then partner these data with data from the National Center for Education Statistics and the Texas Education Agency to collect data in three broad categories: 1) student body statistics, including total students, enrollment by race and ethnicity, English learners, free or reduced lunch eligible students, economically disadvantaged students, and mobility rate, 2) school budgets, including budgets allocated to full-time employees and total operating expenditures per student, and 3) school quality indicators, including Texas A-F scores, student/teacher ratios, state standardized test score percent on grade level, and dropout rates. Each indicator is captured at the individual school level.

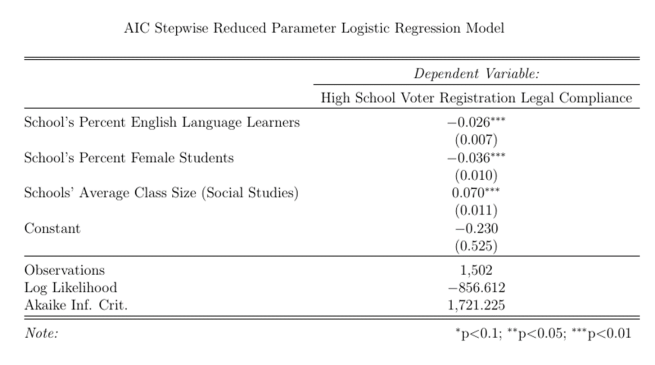

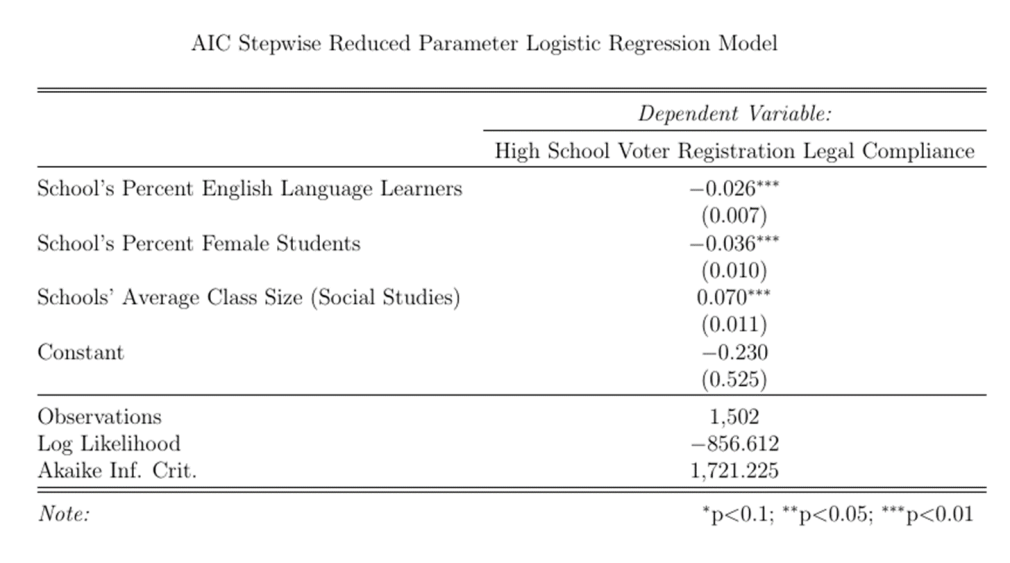

Utilizing this data on Texas high schools’ student bodies, school budgets, and school quality indicators, we estimate a logistic regression to determine which indicators are most closely associated with high schools’ compliance with voter registration requirements. Since our model tests the association of so many variables, we use a stepwise algorithm to choose a reduced parameter model by AIC.

Findings

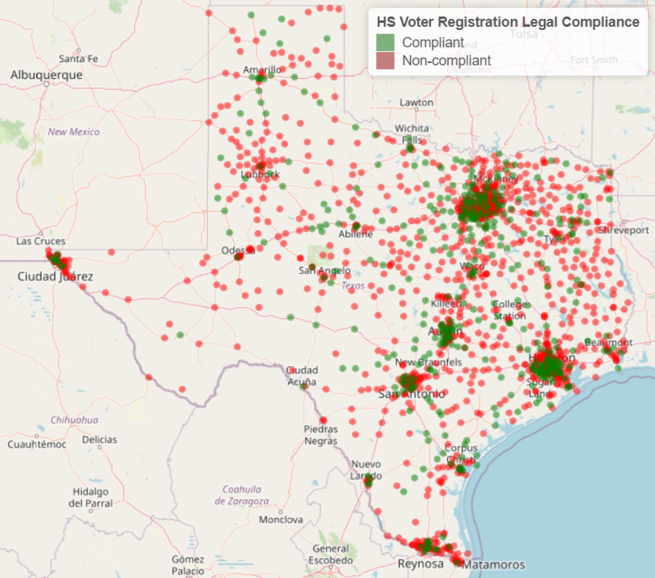

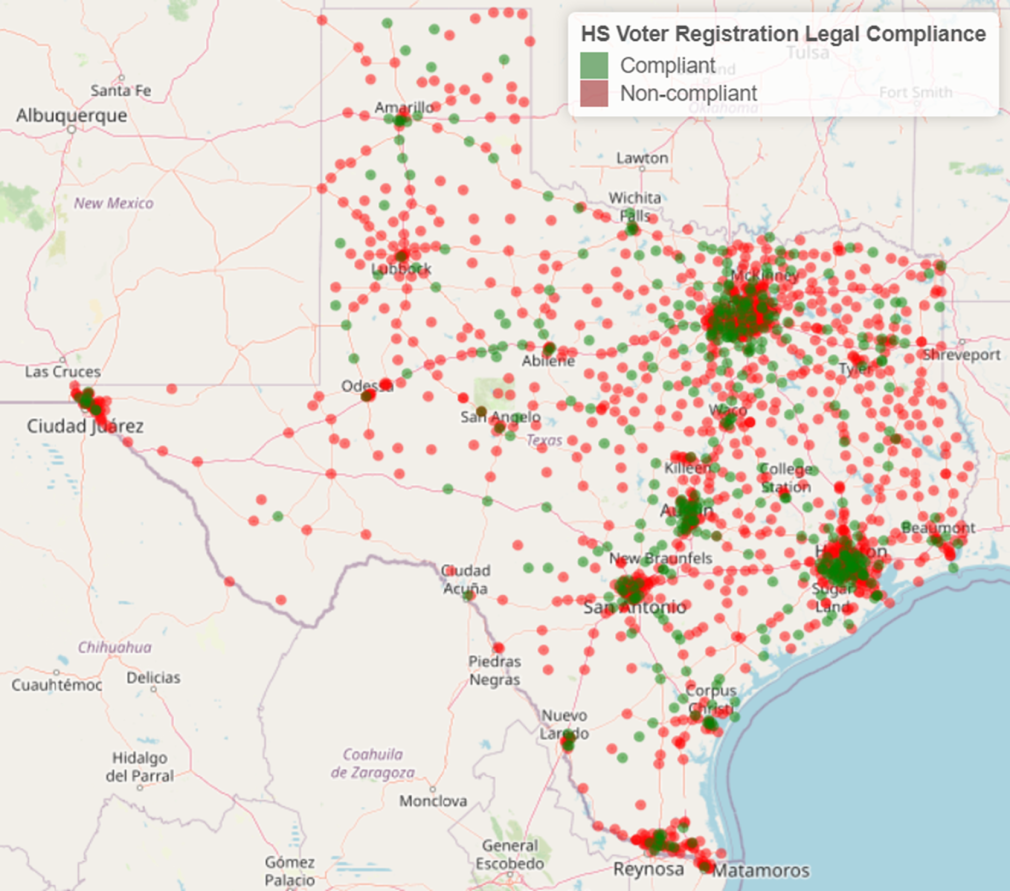

The Texas Civil Rights Project found that from 2016 to 2019 compliance rates doubled, but our analysis finds that even with this increase, only 428 (25.94%) of Texas’ 1,650 public high schools complied at least one time with the state law that requires them to supply voter registration opportunities to students for all the years surveyed. We find the most compliant Education Service Centers (ESCs) are Houston, Fort Worth, Richardson, and Austin (in descending order). The least compliant ESCs are Midland, Beaumont, El Paso, Mt. Pleasant, and Lubbock.

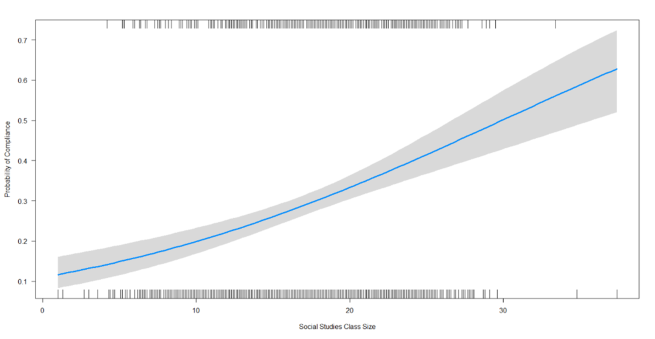

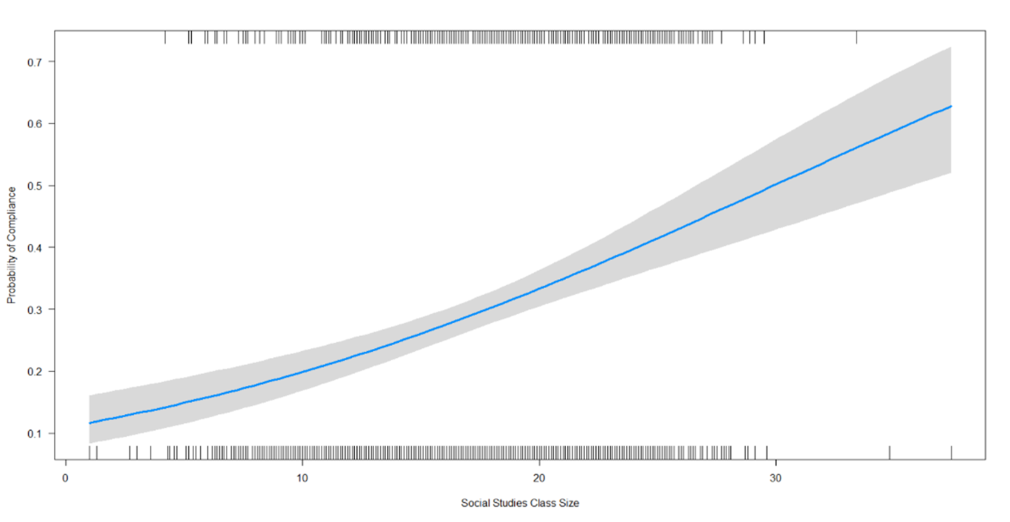

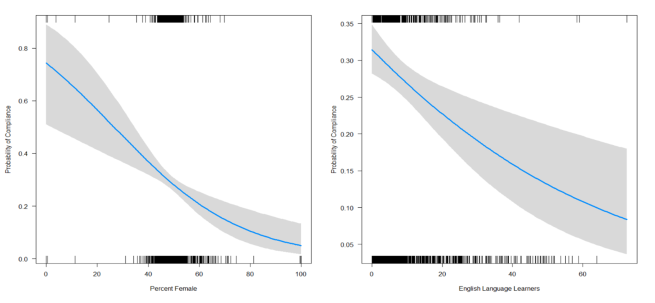

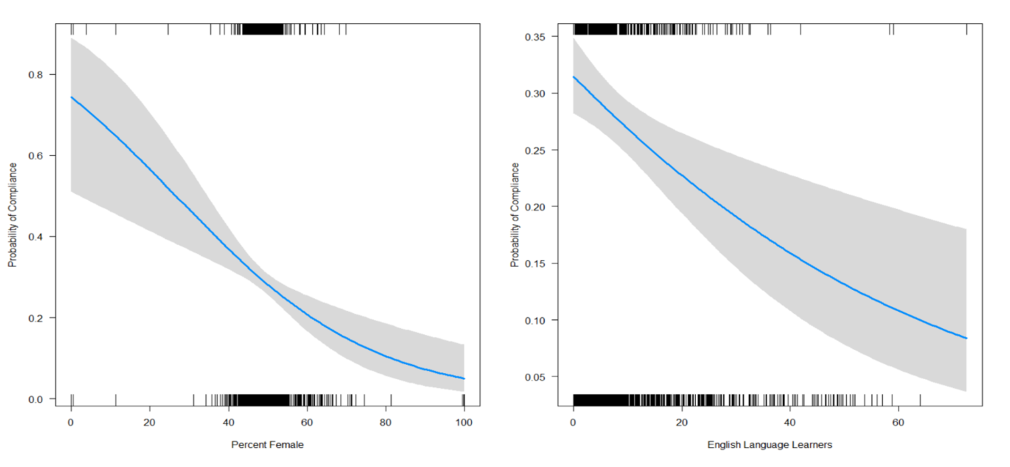

Our logistic regression model finds that compliance - rather than noncompliance - becomes more likely when schools when average (social studies) class size increases. Noncompliance with voter registration requirements is statistically significantly more likely than compliance at Texas schools with larger percentages of female students and larger percentages of English language learners as students. Compliance - rather than noncompliance - becomes more likely when schools when average (social studies) class size increases.

High schools that exhibit larger average class sizes, as measured by their social studies class size, are more likely to comply with voter registration requirements. High schools’ average class sizes in Texas range from 1 student to 37.4 per class, with an average of 17.17 students per social studies class.

High schools with a greater percentage of female students and English language learners have a higher predicted probability of noncompliance with Texas voter registration requirements. Both these groups have been historically marginalized from voting in the United States.

Conclusion

These results demonstrate that more needs to be done to encourage compliance with state registration laws to facilitate greater youth participation in the electoral process. Our findings can be utilized to inform grassroots youth and political advocacy non-profit organizations - as well as state and local education officials - as to how best to target the efforts needed to increase high schools’ compliance, especially in the absence of state-level reform that strengthens the administration of high school voter registration. To target youth voter registration efforts most efficiently, special attention should be paid to communities historically marginalized from voting – especially women and new immigrants. Policy makers, school districts, and individual schools can also ensure their new voters are well-informed by bolstering social studies and civics education.