Vote Choice and Perceptions of Ballot Secrecy in the 2020 Election

The MIT Election Data and Science Lab helps highlight new research and interesting ideas in election science, and is a proud co-sponsor of the Election Sciences, Reform, & Administration Conference (ESRA).

Our post today was written by Eli Mckown-Dawson, Lonna Atkeson, M.V. Trey Hood, and Robert Stein, based on their presentation at the 2022 ESRA Conference. The information and opinions expressed in this column represent their own research, and do not necessarily represent the opinions of the MIT Election Lab or MIT.

Laws and procedures to ensure ballot secrecy are a hallmark of modern democracies.

However, Gerber et al. (2013) show that a significant number of voters do not believe that their ballot is secret at the administrative level, and a majority freely share their vote choices with others. We ask whether their findings generalize to the 2020 election and assess how beliefs about ballot secrecy influenced vote choice. We find that voters have grown more insecure about the secrecy of their ballot and are less willing to discuss their vote with others. These are unremarkable trends, especially given the contentious nature of the 2020 election and persistent claims of voting irregularities since the 2016 election. We also show that these beliefs have widespread effects on presidential vote choice, particularly for those who voted by mail.

Previous Research on Ballot Secrecy

In several papers, Gerber et al.(2013a; 2013b; 2013c; 2014; 2017) and Dowling et al. (2019) show that a quarter of U.S. voters do not believe their vote choices are secret and that three-quarters report sharing their ballot choices with others. They develop two dimensions of ballot secrecy: psychological and social. A ballot is psychologically secret when voters believe their vote choice is secret at the election-administrative level. On the other hand, a ballot is socially secret when a voter does not feel obligated to discuss their vote choices with friends, family, or other members of their social network.

Research on ballot secrecy has focused on whether these beliefs alter voters’ decisions at the ballot box. If a voter does not believe that their ballot is secret, they may be more susceptible to pressure from their social group to change their vote choice rather than vote for the candidate they would otherwise prefer. For these voters, there are social costs and benefits to voting for certain candidates that others in their social or professional networks support or oppose. For example, feeling solidarity by voting the same way as your friends or avoiding possible sanctions in the workplace.

Scholars studying ballot secrecy have found that these beliefs shape voting decisions. Social forces have a greater effect on the vote choices of voters who doubt the secrecy of their ballot, especially those with weaker partisan attachments. Gerber and friends show that weak partisans were more likely to “defect” and vote for the opposing party’s candidate if they believed their vote choice was secret. Similarly, those who vote by mail have also been shown to be less secure in the secrecy of their ballot.

Voter Beliefs about Ballot Secrecy in 2020

First, we assess if beliefs about ballot secrecy have changed in recent years and whether voters have become less confident in the secrecy of their vote. We might expect such a change to arise from the 2016 and 2020 Presidential elections when candidate and President Donald Trump raised doubts about the integrity of both elections and argued that his opponents tried to ‘steal the election.’

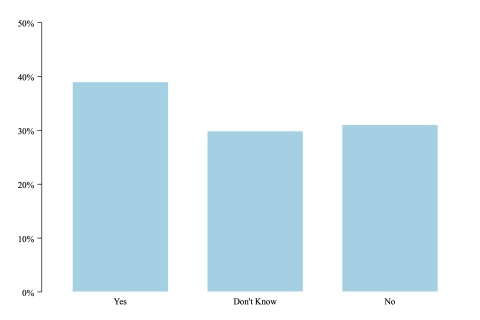

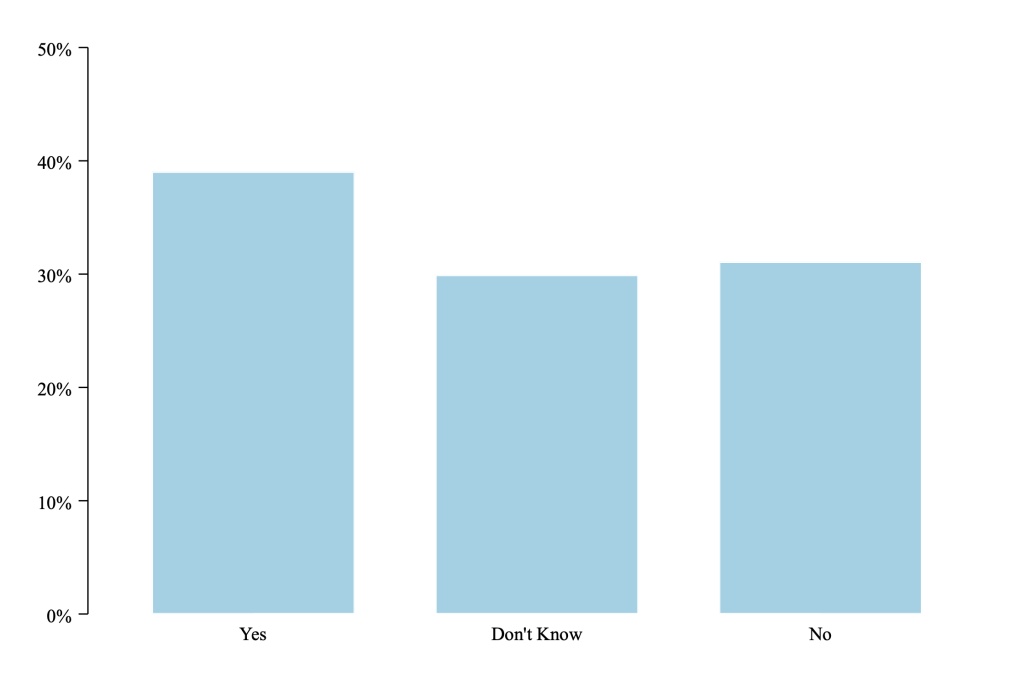

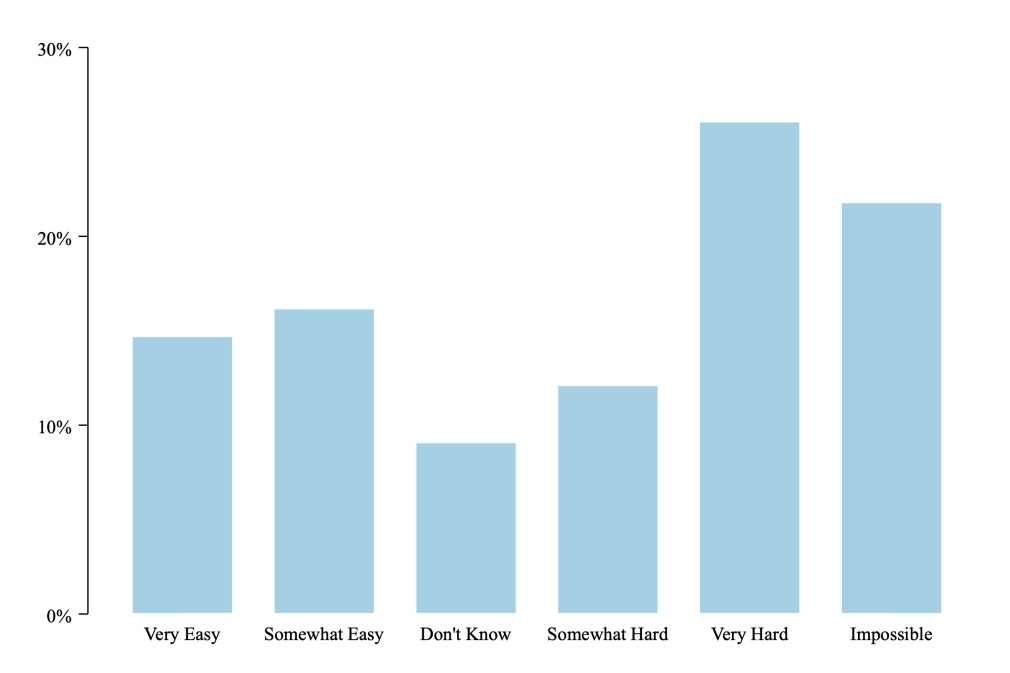

We use questions from The Integrity of Voting in the 2020 Election survey to assess voters’ perceptions of psychological and social ballot secrecy. Figure 1a shows that 40% of voters in 2020 thought that elected officials could access voting records to figure out someone’s vote choice. Figure 1b shows that 31% thought that it would be “very” or “somewhat” easy for politicians, union officials, or their co-workers to figure out whom they voted for.

Figure 1a (left). Do you think elected officials can access voting records and figure out who a voter has voted for?

Figure 1b (right). How easy or hard do you think it would be for politicians, union officials, or the people you work for to find out who you voted for, even if you told no one?

Figure 1a (left). Do you think elected officials can access voting records and figure out who a voter has voted for?

Figure 1b (right). How easy or hard do you think it would be for politicians, union officials, or the people you work for to find out who you voted for, even if you told no one?

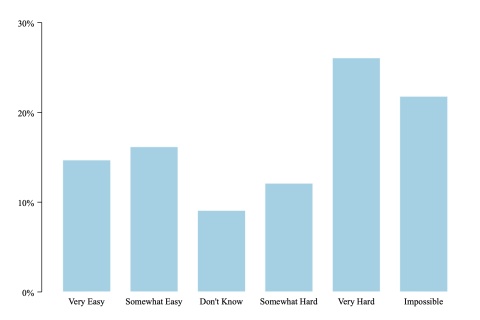

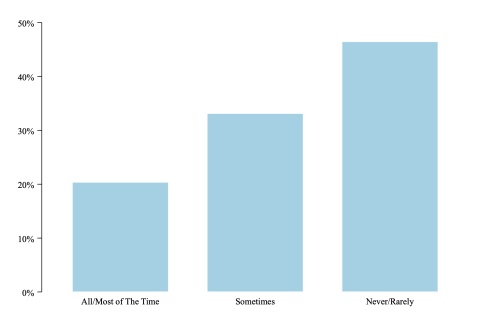

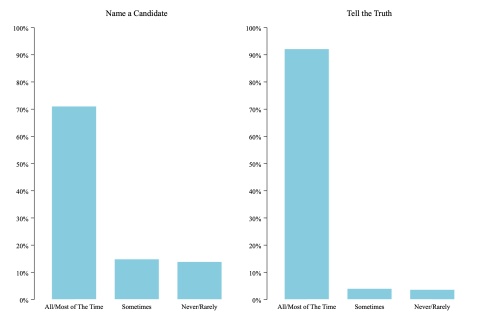

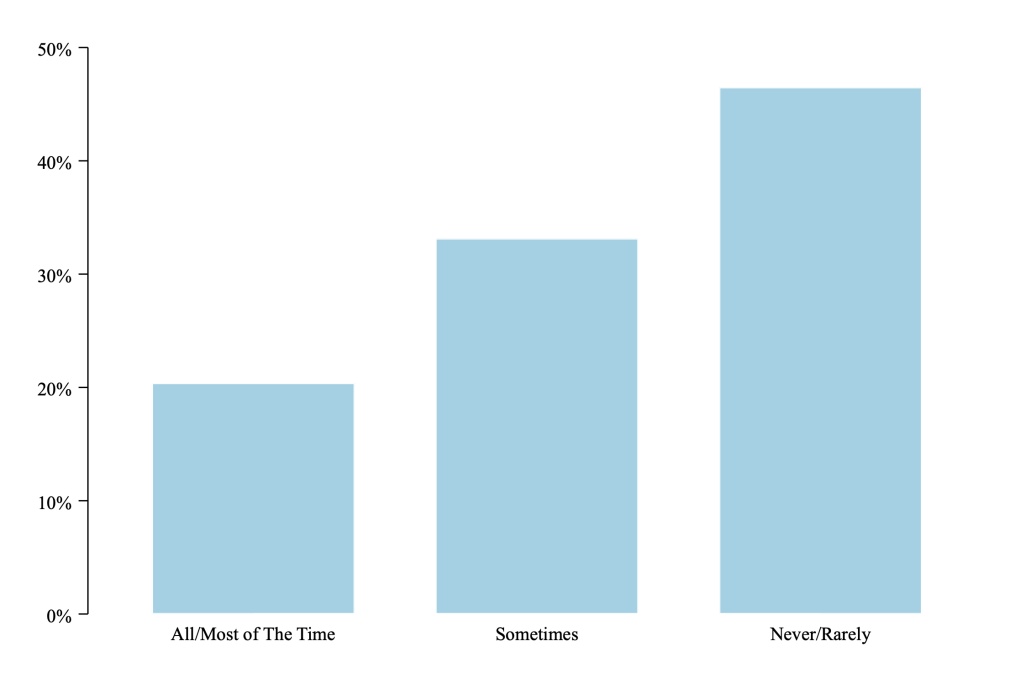

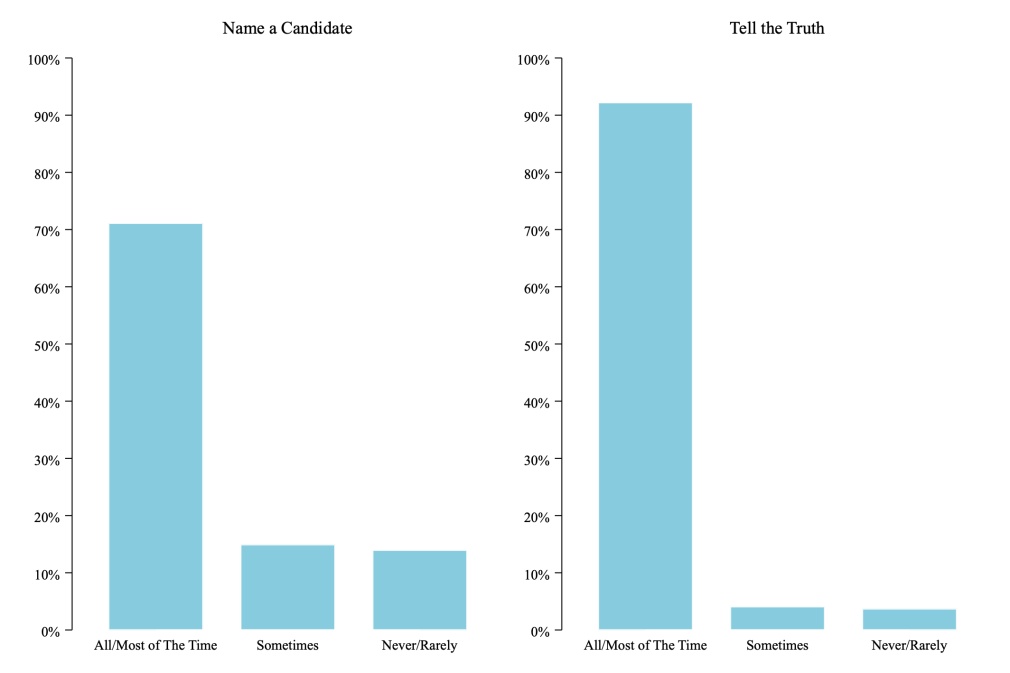

For social secrecy we find that only one-in-five (20%) voters were asked about their vote choice most or all of the time (Figure 1c), but 70% answered nearly all the time when asked, and 90% told the truth nearly all the time (Figure 1d). Compared to Gerber et al’s studies, voters in 2020 were less inquisitive about others’ vote choices and were more constrained from responding and responding honestly.

Figure 1c (left). How often does anyone, including friends or family, ask you which candidate you prefer or voted for?

Figure 1d (right). Naming a Candidate and Honesty when Asked

Figure 1c (left). How often does anyone, including friends or family, ask you which candidate you prefer or voted for?

Figure 1d (right). Naming a Candidate and Honesty when Asked

There are also striking attitudinal differences between Democrats and Republicans. Fifty-eight percent of Republican voters thought elected officials could access their vote choice, while only 20% of Democrats believed the same. Similarly, Democrats were five percentage points more likely than Republicans to share their vote choice when asked. Indeed, we find that, on average, Republicans are more psychologically insecure while Democrats are more socially insecure.

Ballot Secrecy, Vote Choice, and Voting by Mail

We next examine whether there is a relationship between ballot secrecy and presidential vote choice, and, if so, whether the previous conditional relationship between beliefs in secrecy and strength of partisanship has changed. Based on previous research, we expect weak partisans who are psychologically and socially insecure will be less likely to defect and vote for the opposite party.

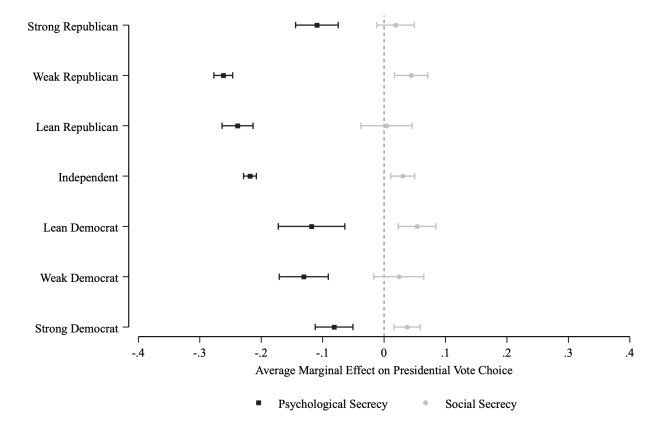

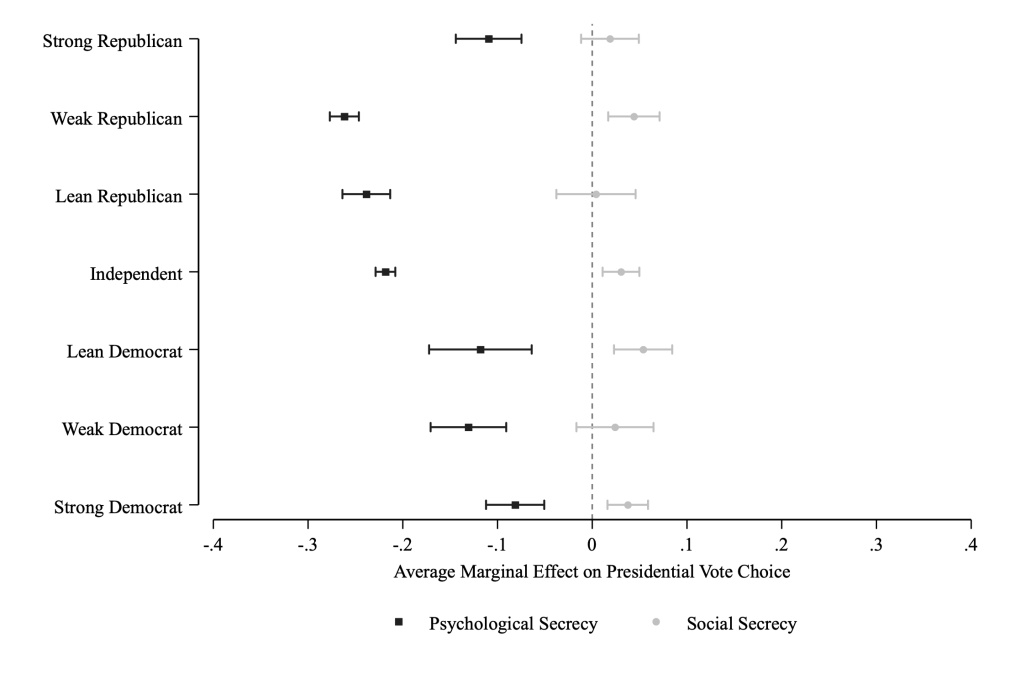

The graph below presents the marginal effects of psychological and social secrecy on presidential vote choice in the 2020 election across all levels of party identification. The two secrecy dimensions are measured using factor scores generated from questions in the Integrity of Voting Survey. Presidential vote choice is a binary variable that equals 0 if a voter chose Biden and 1 if they chose Trump. These values were computed from a logistic regression model of vote choice.

Figure 2. Effect of Psychological and Social Secrecy on Voting for Trump

Strong partisans of both parties who thought their ballot was psychologically secret were less likely to vote for Trump. However, the effect was greatest among independents, weak Democrats, and weak and leaning Republicans. We observe an effect of social secrecy for independents weak Republicans, and weak Democrats. In these groups, those who thought their vote choice was socially secret were more likely to vote for Trump. Contrary to Gerber et al., we find the effects of ballot secrecy in 2020, both social and psychological, work in the same direction for Democrats and Republicans. Regardless of party identification, Psychological secrecy leads to less support for Trump and social secrecy leads to more support for Trump.

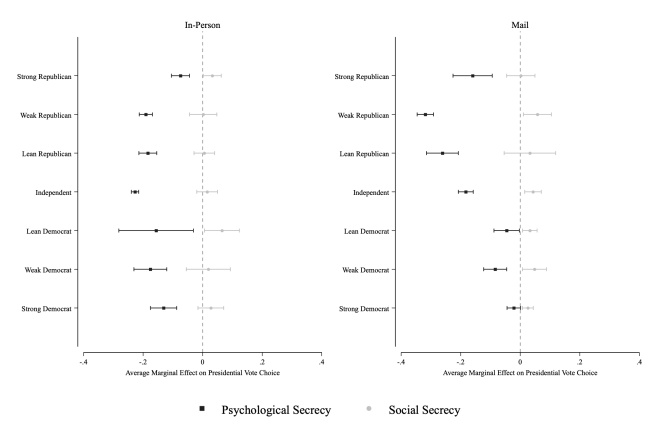

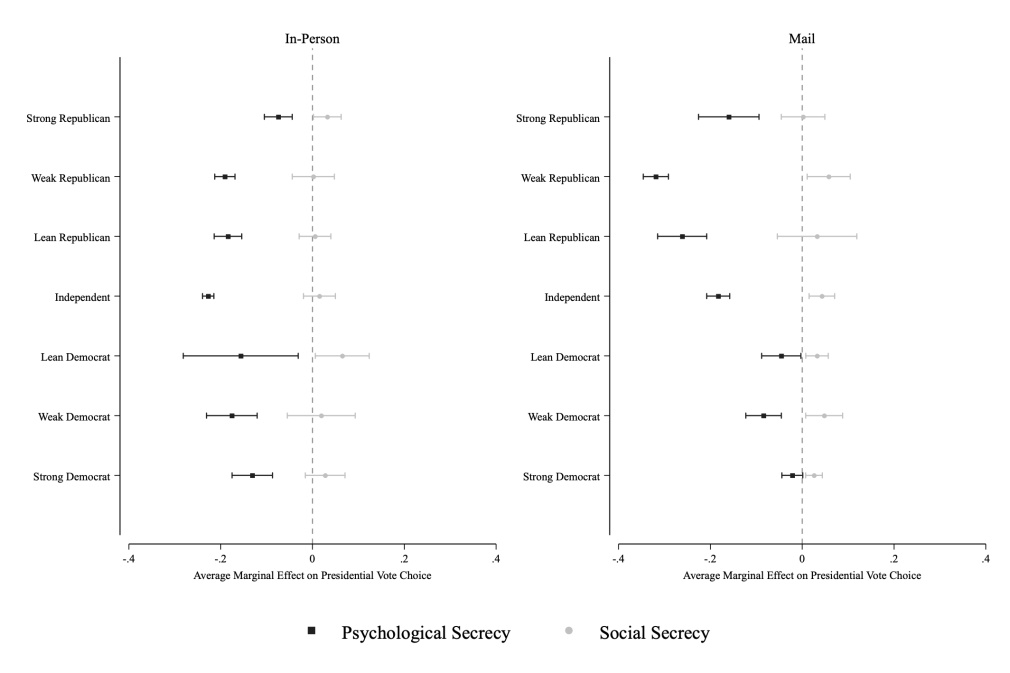

Voting by mail is inherently less private than voting in person. For example, Dowling et al. (2019) find that approximately 20% of mail voters fill out their ballot with someone else in the room. Therefore, we expect to see differences in how psychological and social secrecy affect mail voters compared to in-person voters. In 2020 many chose to vote by mail because they were concerned about Covid-19 and were thus more susceptible to the effects of psychological and social secrecy because their ballot choices were potentially more public. We re-estimated the effects of ballot secrecy on vote choice for mail and in-person voters separately, a The average marginal effects are shown for each partisan group in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Effect of Psychological and Social Secrecy on Voting for Trump: Mail Vs. In-Person

Concerning psychological secrecy, we see a change in degree, but not in kind across different methods of voting. Both graphs show that voters who have more psychological secrecy are less likely to vote for Trump, consistent with Figure 2. Republicans who voted in person were less affected by psychological secrecy than those who voted by mail. However, for Democrats and independents, those who voted in person were more susceptible to the effect of psychological secrecy. For in-person voters, social secrecy has almost no effect on vote choice, but this is not the case for mail voters. For weak Republicans, Weak Democrats, and independents who voted by mail, higher social secrecy was correlated with a higher probability of voting for Trump. Overall, all mail voters were slightly more susceptible to social secrecy effects, and Republicans who voted by mail were more affected by psychological secrecy.

Secrecy in the 2020 Election: A Campaign Issue?

While beliefs about ballot secrecy remain correlated with presidential vote choice, the nature of this effect has changed substantially. Previous findings suggested only weak partisans were less likely to defect from their party’s Presidential candidate when they were unsure about ballot

secrecy. In 2020, we found that all voters who were unsure about their ballot’s psychological secrecy—both Democrats and Republicans—were more likely to vote for President Trump, although the effect is smaller for strong partisans on both sides. This may suggest that—due to Trump’s increased focus on the integrity of the vote during and after the 2020 election—psychological secrecy became a campaign issue that polarized the electorate along partisan lines more than in previous elections. In our case, all voters who believed Trump’s message about election administration were more likely to vote for him, and those that did not embrace Trump’s message about election fraud were less likely to do so.

Social secrecy has a more muted effect on the vote choices of 2020 voters. Weak partisans from both parties and independents who were confident in the social secrecy of their ballot were more likely to vote for Trump. This finding also runs counter to previous research on ballot secrecy, which shows a defection effect. We interpret these findings to suggest that the 2020 election produced incentives for Trump rather than Biden voters to keep their vote secret. In keeping with this framework, defections to Trump among Democrats were greater among those most socially insecure.

Voting by mail—another polarizing campaign issue in 2020—also conditions how belief in ballot secrecy impacts vote choice. While both in-person and mail voters are affected by psychological secrecy, the effect is larger for those who voted by mail. Similarly, social secrecy does not impact in-person voters, butonly mail voters who believe their ballot is more socially secret were more likely to vote for Trump.

These findings raise important questions about mail voting, which has risen steadily over time, even before the Covid-19 pandemic drove many voters to avoid in-person voting. In many other states, voters do not have options for in-person voting. How might the social nature of VBM affect voter decision-making in these states compared to states where voters have options to vote in-person? Also, what specific elements of in-person voting enhance confidence in the secrecy of the ballot? These are relevant questions for further study, especially as more states and voters embrace VBM elections, especially those that only allow for VBM.