Don't Dismiss Digital Immigrants

Poll Workers and New Election Technologies

The MIT Election Data and Science Lab helps highlight new research and interesting ideas in election science, and is a proud co-sponsor of the Election Sciences, Reform, & Administration Conference (ESRA).

Our post today was written by Stephanie L. DeMora, Melissa R. Michelson, and Dari S. Tran, based on their paper presented at the 2021 ESRA Conference. The information and opinions expressed in this column represent their own research, and do not necessarily represent the opinions of the MIT Election Lab or MIT.

Introduction

Poll workers are critical to the election process. With little on-site supervision, they are responsible for making decisions about who can vote, the length of time that individuals wait to vote, and to some degree, whether votes are counted accurately.

The (somewhat accurate) stereotype about poll workers is that they tend to be older women (Burden and Milyo 2015). Another common stereotype about older people, sometimes dubbed digital immigrants, is that they are uncomfortable with and poor adopters of new technology (Glaser et al. 2007). Many other poll workers are high school students, often recruited as part of civic education efforts. The stereotype about these digital natives is that they are comfortable with and quick to adapt to new technology (Hall, Monson, and Patterson 2007). As more of the voting process has shifted to electronic technologies, local election officials have faced questions and concerns about the degree to which their older poll workers will adapt to those new tools (Prensky 2001), but data we have collected from San Joaquin County, California suggests otherwise.

Voters evaluate older poll workers less favorably compared to their younger counterparts (Hall and Stewart 2013). Older poll workers are generally less comfortable with touch-screen direct recording electronic (DRE) machines than younger poll workers (Spencer and Markovits 2010). In a study of the June 2006 election in California, Glaser and their colleagues noted that precincts with higher percentages of retirees working as poll workers recorded more voting efforts. Similarly, Hall, Monson, and Patterson found in their survey of poll workers in Ohio and Utah that respondents over the age of 55 tended to report more start-up or shut-down problems with electronic equipment than did younger poll workers.

Contrary to these stereotypes and results from previous efforts, we find that older workers were no more likely to report concerns with new digital voting equipment and that they were no more likely to experience problems with the equipment on Election Day.

We partnered with the Registrar of San Joaquin County to conduct an evaluation of the training and performance of poll workers during the March 2020 primary election. Poll workers completed paper surveys before and after their face-to-face poll worker training sessions.

Overall, 1,402 individuals completed the surveys. Over one-third (35.5%) were students, with an average age of 17.7; the average age of non-student poll workers was 54.3. Two-thirds of our survey respondents were women.

After the election, we reached out to poll workers to invite them to participate in one of two face-to-face focus groups. Participants were compensated for their time. Participants included 13 non-students and two student poll workers; 12 of the 15 focus group participants were women.

Results

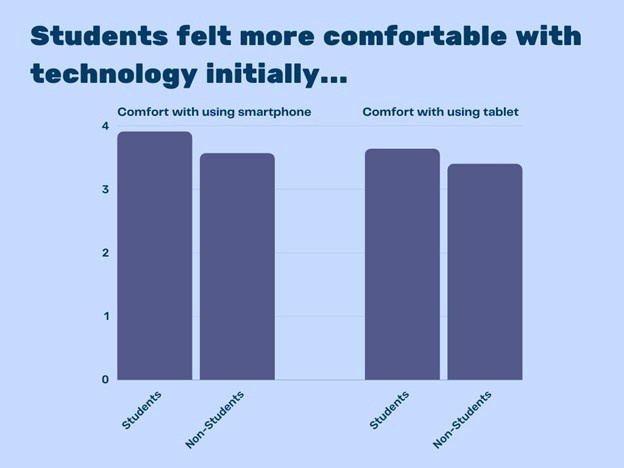

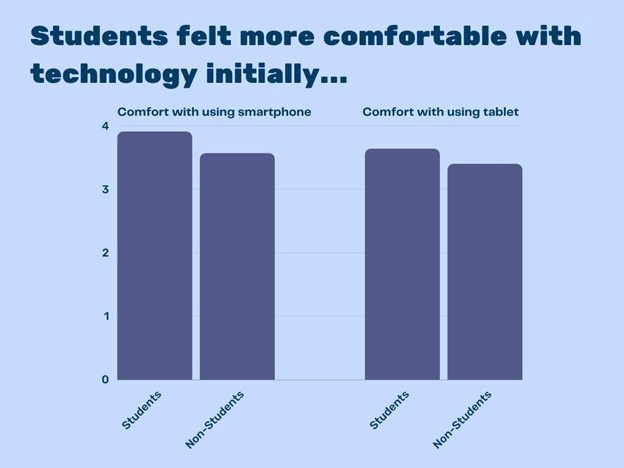

Student poll workers did report more comfort with smartphones and tablets before the training, compared to non-students, but also said they felt less prepared and were slightly less optimistic that technology would make the check-in process easier.

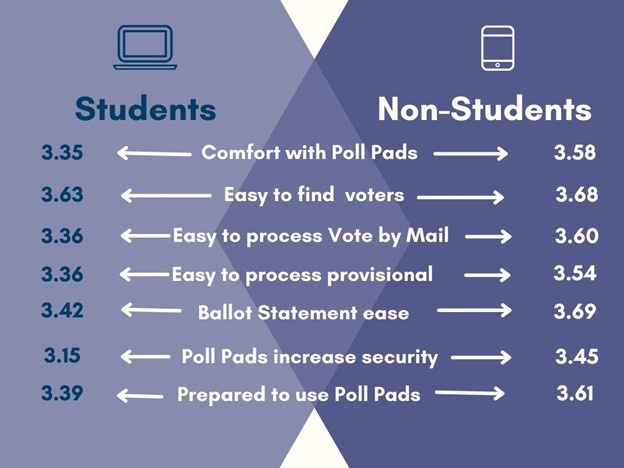

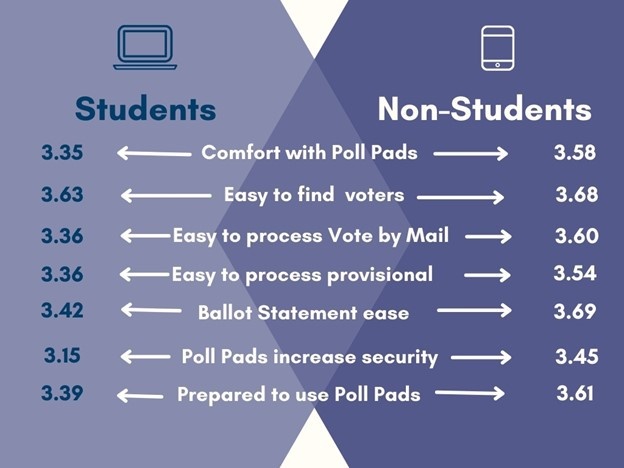

After the training, students felt less comfortable with the Poll Pads than non-students. Students thought it would be harder to use Poll Pads to look up voters and were more concerned about the difficulty of using Poll Pads to process VBM voters, provisional voters, and to balance the Ballot Statement. Students thought the Poll Pads were less likely to make voting more secure. Students felt less prepared to use Poll Pads on Election Day.

Focus Group Data

Our non-student focus group participants voiced common stereotypes about students as digital immigrants who would easily be able to adjust to using the Poll Pads and about older workers (and voters) as being less confident about their ability to do so.

Older poll workers were happy to have students take charge of the Poll Pads, given students’ assumed proficiency and their own discomfort with the new technology. One focus group participant noted, “We were a little worried about the [poll] iPads, but we had four students there.” But other poll workers shared that their initial hesitancy often turned out to be overblown and that they found the poll pads relatively easy to use.

Even experienced poll workers hold stereotypical expectations about the ability of younger and older people to use new technologies. At the same time, older poll workers had no trouble using the poll pads and often found them convenient and even enjoyable to use.

Polling Location Data

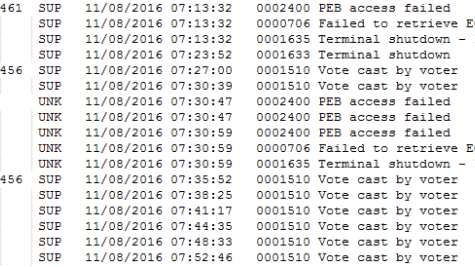

The San Joaquin Elections office provided us with a list of problems that occurred at each polling location. The number of problems ranged from 1 to 6; most (87.6%) polling locations recorded 1–3 problems.

We find no evidence that the average age of workers or the percentage of student workers at a polling place has any impact on the number of poll pad problems that occurred at the polling locations.

Conclusions

Defying conventional stereotypes, we find older poll workers no less able to effectively work with new polling place technologies, and higher rates of uncertainty among younger poll workers. We also find no evidence that younger workers are less (or more) likely to have an effect on the rate of polling problems on Election Day.

As noted by Wang, Myers, and Sundaram (2013), age is but one factor that may shape one’s aptitude to engage with novel technology. While poll worker recruitment efforts aimed at attracting young people may pay democratic dividends as more previously politically unengaged people recognize the value of electoral participation through pollworking, these efforts are likely not the panacea to cure all poll worker challenges with new technology.