Maintaining the Machinery of Democracy

Assessing the Quality of Voting Equipment in the 21st Century

The MIT Election Data and Science Lab helps highlight new research and interesting ideas in election science, and is a proud co-sponsor of the Election Sciences, Reform, & Administration Conference (ESRA).

Nadine Gibson recently presented a paper at the 2018 ESRA conference entitled, “Maintaining the Machinery of Democracy: Assessing the Quality of Voting Equipment in the 21st Century.” Here, she summarizes her analysis from that paper.

Despite the obvious relevance of a voter’s election experience is to their subsequent democratic participation, the literature on voting and elections has focused overwhelmingly on abstract voting behavior, rather than the act of voting itself.

Since the controversial 2000 presidential election, the demand for information about improving the conduct of American elections has been increasing. Our current knowledge of how much localities spend on voting equipment, however, is speculative and anecdotal. According to a national survey of local election officials themselves, voting technology is the most daunting issue in upcoming elections. Without a sense of the costs of elections, it will become increasingly difficult for localities to take preventative measures before an Election Day catastrophe.

Underlying the concerns of local election officials about the state of their voting equipment is the notion that voting technology has a substantial impact on the quality of American elections. Voting equipment can quite literally be considered the machinery of democracy. It is important, therefore, to understand the relationship that the quantity and quality of voting equipment has on voting behavior. More specifically, can turnout and the voting experience be improved with more voting equipment? What about with newer voting equipment?

Funds from the MIT Election Data & Science Lab (MEDSL) were used to build a dataset on the cost of voting equipment, using data from local-level contracts for the acquisition of voting equipment. The states included in this analysis are California, Delaware, Illinois, Nebraska, New Mexico, Nevada, Rhode Island, Texas, Utah, and Vermont. Future iterations of this study will include a more representative sample of states (or a sample of counties within a representative sample of states).

County- and municipal-level contracts for the acquisition of voting equipment provide data on 1) the cost per voting equipment unit, 2) geographic variability in cost, 3) number of units, 4) services subcontracted to vendors. Variables derived from these contracts include age of voting equipment, number of units per precinct, number of units per registered voter, dollars spent per registered voter, and average amount spent per unit of voting equipment.

To access information on the acquisition of voting equipment and vendor services, I requested copies of county contracts from the respective custodians of election records. This was done through open records requests — a process by which a citizen may ask to obtain a copy of or inspect documents that are considered public information, but not made publicly available. Data collected from the contracts was then merged with turnout and demographic data; these were taken from the Census Redistricting Data Program, due to its comprehensiveness and availability. This merging process is possible through the inclusion of geodesic place codes such as Federal Information Processing Standards (FIPS) code.

Unlike other aspects of American politics, elections are inherently geographic. This study used spatially weighted regression analysis to account for regional variation in turnout. Methodologically, the results of this study suggest that modeling spatial data appropriately does have substantive implications on regression analysis. By including specifications for spatial autocorrelation in the error term, the fit of the model was improved.

In terms of substantive findings, the age of voting equipment also seems to influence turnout. Counties using older systems are associated with lower the turnout. These results confirm worries of those who believe that voting equipment in the United States is woefully outdated, and that this is an important issue for elections administration to address. At the end of the day, voting machines are like any other piece of computerized technology. Unlike punch-card and lever voting systems, which are mechanical in nature, DRE and optical scanning voting technology cannot last for decades-upon-decades. Despite the flaws of mechanical systems, they were long-lasting and did not require proprietary knowledge in their maintenance. If the future of voting technologies lies in computerized systems, it is prudent for localities to prepare to update these systems at regular and short intervals.

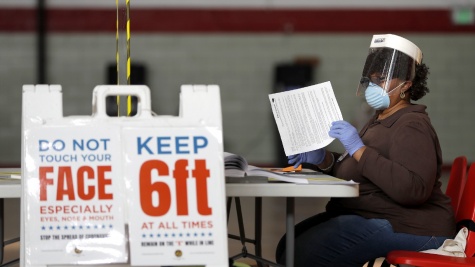

The empirical evidence in support of county purchases of voter outreach efforts should be reassuring for local election officials. Voter education programs are a concrete and practical solution for localities in improving the turnout and the Election Day experience for their constituents. Voter education programs can include elements such as posters, pocket cards, social media, and in-person demonstrations on how to use voting equipment. These results suggest that by providing voters with information on what they can expect at the polling place, voters are able to cast their ballots more quickly and confidently.

In contrast, the results of the coefficient estimates for project management services from vendors is more troubling. These results could, however, be a proxy for localities that are least able to manage elections due to the size of the election office. In many counties, the official responsible for running elections is also responsible for many other essential government tasks. As vendors are not in fact public employees, their objectives may not be as in-sync with the interests of the public we would hope.

One of the secondary conclusions that can be inferred from the results of this study is that hyper-federalized election systems are beneficial to maintaining a healthy American democracy. The evidence presented supports the notion that counties are more in-tune with the needs of their voters. Local election officials are more likely to understand the traffic patterns of individual polling places and the types of machines that will best accommodate their constituency. When counties take over the reins of acquiring voting equipment, they may in fact be able to directly increase turnout.