MEDSL Explains: Voting Technology

A look at the mechanics behind how Americans vote

Voting uses technologies that range from old-fashioned hand-counted paper ballots to new(er)-fangled electronic voting machines that resemble ATMs. Until the disputed 2000 presidential election, most voters didn’t give a second thought to how they cast their ballots — but since then, voting technology has become much more controversial.

In general, voting technologies have developed in parallel with advances in information processing technology. Paper ballots were the only means of voting until the late 1800s, when automation began to be used to assist in counting votes. Nowadays, almost all ballots in the U.S. are counted using computer-assisted technologies.

A major feature of the 2000 recount controversy in Florida was the performance of punch-card voting machines, which were beset with problems associated with poor ballot design and “chads” that failed to separate from the punch cards correctly. Antiquated voting technologies were rapidly replaced after 2000, and increasingly, precincts began to switch to using purely electronic machines. This, in turn, prompted controversies over whether those machines could be trusted to record votes accurately. That controversy has reversed the trend toward using purely electronic machines and led to their decline in recent years, and contributed to sustained pressure for more sophisticated methods to audit the performance of voting machines.

Starting in the early 2000s, voting machines in many states and precincts were replaced en masse, spurred on by the availability of federal funds to buy new equipment under the passage of the Help America Vote Act. By the mid-2010s, though, much of this equipment had become obsolete, which led the Presidential Commission on Election Administration to note that there was an “impending crisis” in voting technology.

Types of voting technologies

Historically, five types of voting machines have been used at least somewhere in the United States: hand-counted paper, mechanical lever machines, punch-card machines, scanned paper ballots, and direct-recording electronic devices. Within each of these types, though, there is great variability in terms of how they are used.

- Hand-counted paper ballots are marked by hand, usually with an X indicating the voter’s choice next to a candidate. Ballots are then counted by hand, usually in the precinct where they were cast. Nowadays, hand-counted paper ballots are rarely used in the United States; they are more common in other countries, especially those that typically have only one race on the ballot at a time.

- Mechanical lever machines were first used in the 1890s. These machines are operated by the voter, who indicates their choice by pressing a lever next to the candidate they prefer. The privacy of each voter is protected by a curtain, which they can pull around the machine when they enter by operating a large lever. (You can see an example of this in the top right photo above.) In these voting machines, there is an interlocking mechanism that prevents the voter from over-voting — that is, voting for more than the allowed number of candidates. Once the voter is finished, they pull the large lever again; when they do, the counters associated with their choices are advanced by one, and the machine is readied for the next voter. At the end of Election Day, votes are counted by opening the machine and reading the numbers on the counters associated with all the candidates. By law, mechanical lever machines may no longer be used in federal elections, although they’re sometimes still used in state and local elections.

- Punch-card voting devices were developed in the 1960s and relied on modified Hollerith cards to record votes. In the most common version of the punch-card machine, a blank pre-scored card is inserted into a holder. The holder contains a ballot and a set of targets associating each choice with a punch position on the card. If a voter wants to vote for a candidate, they use a stylus to dislodge a chad (the pre-scored bit of paper). This creates a hole in the card associated with the candidate’s number. When the voter is done, they take the ballot card and deposit it in a ballot box. At the end of Election Day, the ballots are counted using a card reader, usually in the central election office. Like lever machines, punch cards may no longer be used in federal elections, although they are sometimes still used in state and local elections.

- Scanned paper ballots were also first used in the 1960s. Essentially, the technology used to scan paper ballots is the same used to score standardized tests. The ballot itself is marked in a private booth. In most cases, a voter uses a black pen to darken a circle next to their preferred candidate’s name. (A less common method is to use a pen to complete an arrow next to the name.) The voter then places the completed ballot in a box. At that point, there are two primary methods of scanning and counting ballots: With precinct scanning, a scanner sits directly on top of the ballot box, and the ballot is scanned as it’s being deposited. Votes are then counted at the end of Election Day by running a procedure on the scanner that prints out the vote totals associated with that precinct. The precinct totals are then transferred (on paper or electronically) to the central election office. With central scanning, ballots are not scanned at the polling place as they are placed in a ballot box. Instead, ballots are returned to the central election office at the end of Election Day, where they are scanned by a high-speed scanning machine.

- Direct-Recording Electronic (DRE) machines first came into widespread use in the 1970s. The earliest DREs were essentially electrical versions of mechanical lever machines, with push buttons replacing the levers and electrical storage devices replacing mechanical counters. Nowadays, DREs are essentially portable computers that have been configured to display ballot choices and then to record votes electronically. Ballot choices are increasingly offered on a computer touch screen, but some systems still rely on a paper display. Most modern DREs allow the voter to indicate a vote by pressing on the touch screen directly, although some systems rely on push buttons. The earliest DREs recorded the votes cast entirely on internal memory units. Increasingly, however, DREs also include a paper record called a Voter-Verified (or Verifiable) Paper Audit Trail (VVPAT) that can be used to audit or recount the election.

The recent history of machines & voting

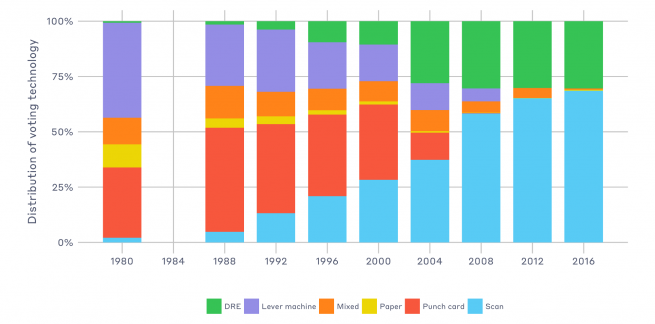

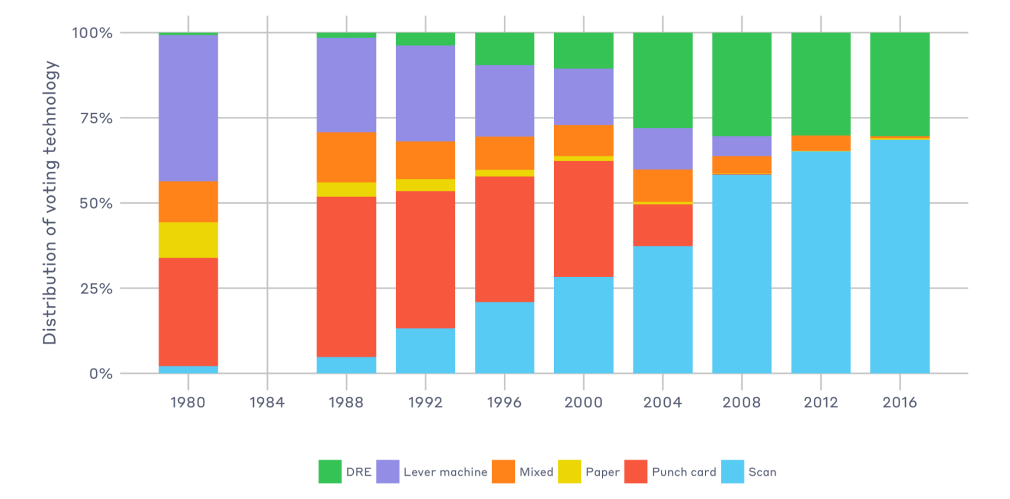

The overall mix of voting technologies used in the U.S. has shifted significantly over the past generation — just take a look at the graph below to see how much it’s changed. In 1980, a plurality of voters used mechanical lever machines, with a significant fraction using punch cards. Scanning technologies had only recently begun to be used; the vast majority of voters who cast their ballots on paper had those ballots counted by hand. (Voters listed as using “mixed” systems lived in counties that used a variety of voting technologies, usually a mix of hand-counted and scanned paper ballots.)

Source: Election Data Services. Note that data are not available for 1984.

From 1980 to 2000, mechanical lever machines and hand-counted paper ballots began their gradual decline in favor of a growth in optical scanners and DREs. In response to the Florida recount fiasco of 2000, Congress passed the Help American Vote Act (HAVA) in 2002, which banned the use of lever machines and punch cards in federal elections. HAVA also required that all precincts have at least one voting machine accessible to voters with disabilities. The effect of HAVA on the selection of voting technologies is clear: the preexisting decline in the use of punch cards and lever machines accelerated, while the use of DREs spiked (before leveling off) and the growth in scanning continued apace.

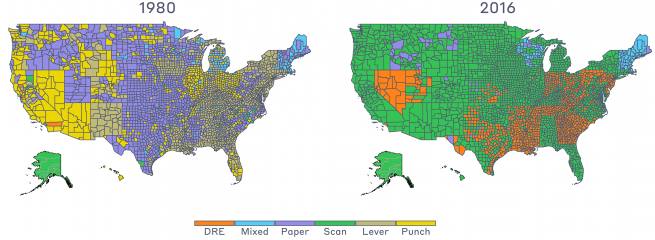

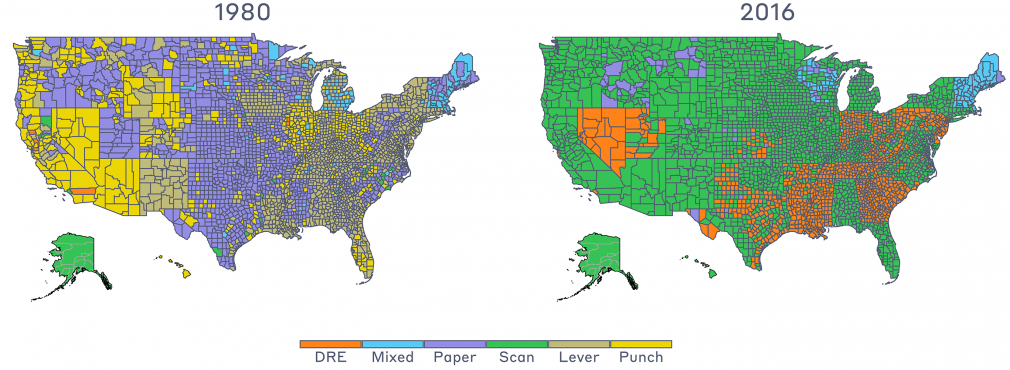

The geographic distribution of voting technologies has also changed over the past generation. Take a look at the two maps below. While there are exceptions, in 1980 mechanical lever machines were primarily used east of the Mississippi River, while punch cards dominated in the West. More rural areas primarily used hand-counted paper. By 2016, scanned paper dominated the western U.S. while DREs dominated the East. (Counties labeled “mixed” in the East use both hand-counted and scanned paper ballots.) Only a handful of very small counties continue to use hand-counted paper ballots.

Why technology?

Two diametrically opposed questions frequently arise in the consideration of voting technologies:

“Why do we rely so much on computers to record and count ballots?”

and,

“Why don’t we vote using the Internet or cell phones?”

We’ll address the first question first:

The fact that one-tenth of American voters were still casting ballots on hand-counted paper as recently as 1980 is evidence that there is no direct correlation between Americans’ love of technology and the use of computer technology for voting. Still, the rise of automation in casting and counting ballots can be explained in terms of some special circumstances that are related to administering elections in the U.S. The most obvious one is the length of American ballots. The U.S. has the longest ballots in the democratic world, which is both the result of federalism (with three levels of officials to be elected) and the general distrust in the U.S. of appointed officials, which has increased the number of elected offices on ballots. Without automation, it would take weeks, if not months, to count ballots in many places, with a significant chance of human error. In addition, in the history of election reform in the U.S., putting ballots under the control of an automated system has often been viewed as a way to minimize fraud such as ballot-box stuffing and ballot theft.

The U.S. also has a commitment to making secret ballots accessible to people with disabilities — a commitment that is difficult to achieve without the use of computers.

DRE controversy

The role of computers in recording and tabulating votes has been a major topic of the policy debate on voting technologies since 2000. One especially controversial issue has been the use of electronic voting machines that rely solely on electronics to record votes, without any paper backup. Despite the fact that the research of Roy Saltman and Rebecca Mercuri questioned the wisdom of using paperless voting systems before 2000, the explosion in the use of DREs after 2000 led to a corresponding expansion of the controversy.

The opposition to DREs was spurred on by political activism within the computer science community. Notable among the leaders was Professor David Dill of Stanford University, founder of Verified Voting, which has continued to be a significant voice in opposing paperless voting systems and advocating for post-election audits. In large part due to the work of this community, the use of DREs has declined in recent years. Furthermore, DREs that are deployed increasingly have a Voter-Verifiable Paper Audit Trail — in the 2016 election, roughly one-third of all DREs had a VVPAT. These VVPATs are sometimes incorrectly referred to as “receipts,” because they often involve printing out the choices that a voter has made in a manner that resembles a cash register receipt. Voters are not actually allowed to take VVPATs with them (as a safeguard against vote selling), so they aren’t considered receipts.

But what about the second question: what’s to stop us from exploring ways to vote online, or on our cell phones?

Once again, the computer science community has been an important resource on this, helping to identify issues associated with voting via the Internet. Among the most significant problems with Internet voting are the ability of malicious actors to intercept a vote cast remotely, and “denial-of-service” attacks that disable the computer systems that receive votes. A few countries around the globe have experimented with voting via the Internet (notably Estonia), and interest has recently grown around the use of blockchain technology to sidestep some of the issues with voting online or from cell phones, but by and large the scientific consensus is that this remains an issue that needs more research before it can be brought into practice.