Rescheduling Local Elections to Make Democracy More Representative

The MIT Election Data and Science Lab helps highlight new research and interesting ideas in election science, and is a proud co-sponsor of the Election Sciences, Reform, & Administration Conference (ESRA).

Our post today was written by Zoltan Hajnal, Vladimir Kogan, and G. Agustin Markarian, based on their paper presented at the 2021 ESRA Conference. The information and opinions expressed in this column represent their own research, and do not necessarily represent the opinions of the MIT Election Lab or MIT.

Elections are the building block of democracy. Yet, despite the centrality of the vote for the functioning of democracy, relatively few Americans turn out in the typical contest. And nowhere is that problem worse than at the local level.

In contests for mayor, city council, school board, and the like, turnout can and often does fall below ten percent of the adult population. Even more alarming is that the people who do casts ballots in these local contests don’t look like those who stay home. Across the nation, local voters are much more likely than nonvoters to be white, well-off, well-educated, older, and generally advantaged.

In other words, those who by many measures are the most in need of government support may have the least say in what government does. That is particularly troubling given how much is at stake at the local level. Every year local governments spend almost two trillion dollars. Local governments also provide core functions like education, police and fire protection, and transportation that are critical for individual well-being.

Moving Election Dates?

Is there anything we can do about America’s uneven local elections? To date, existing research has uncovered few, if any, tools that would fully address these imbalances. In this project we investigate the potential of local election timing reform to make local democracy more representative. The underling question is simple. Should jurisdictions hold local elections on the same day as statewide contests, or should these offices be filled through stand-alone elections on some other day of the year?

There is a clear logic to moving to on-cycle elections that coincide with statewide or national contests. Moving to on-cycle local elections makes voting in local contests less costly. When local elections are not held on the first Tuesday in November with other statewide and national races, local voters need to learn the date of their local election, find their local election polling place, and make a specific trip to the polls just to vote in local contests. If, however, local elections occur on the same day as presidential or midterm contests, local voting is almost costless for a voter. Citizens who are already casting ballots for higher level offices need only check off a few more boxes further down the ballot.

Research shows that that this small change in timing makes a huge difference in turnout. Every study that has looked at election timing has found that moving to on-cycle elections doubles turnout (Marschall and Lappie 2018, Kogan et al 2018, Anzia 2013, Hajnal 2010). These results suggest that the single most important change that municipalities can undertake to increase turnout is moving local elections to November of even years.

What we don’t yet know is whether this increase in turnout translates into a more even democracy. Does higher turnout associated with on-cycle elections also mean a more representative electorate less skewed by race, class, and age? On this question, we have few systematic answers.

Research Design

In this study, which is forthcoming in the American Political Science Review, we construct a panel of California city elections covering the years 2008 through 2016 to examine how the racial demographics, socioeconomic status, age, and political orientation of voters who turn out to vote in a city change as the timing of elections shifts. Specifically, we combine information on election timing with detailed micro-targeting data that includes voter demographic information. Because cities regularly change their election timing, we can examine how election composition differs within the same city, depending on when votes are cast.

Results

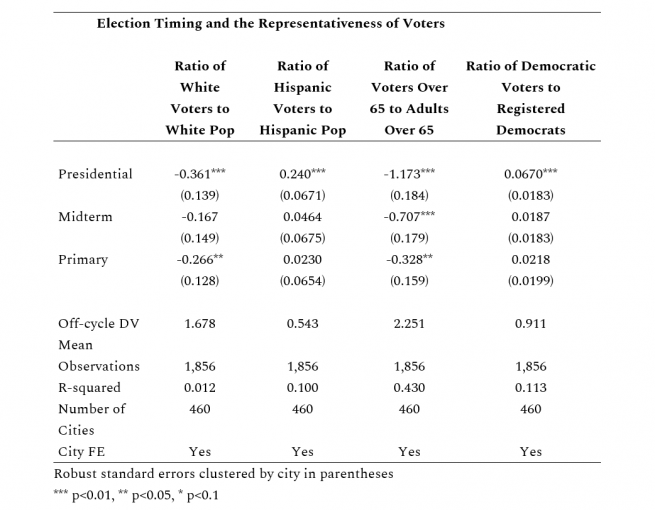

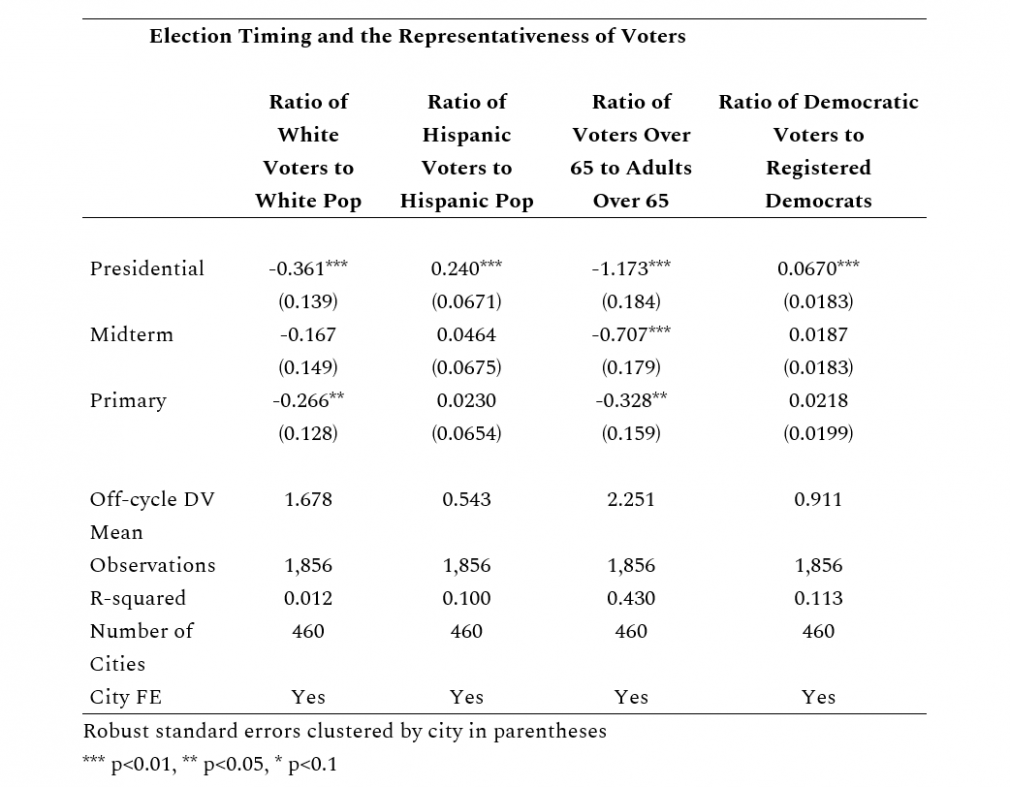

Our analysis demonstrates that that on-cycle elections make the electorate substantially more representative in terms of race, age, income, and partisanship. Some of those results are displayed in the table below, which assesses the impact of election timing in all California cities between 2008 and 2016 on voter race, age, and partisanship. The dependent variable in each case is a measure of representativeness — each group’s share of voters in an election divided by that group’s share of the city’s voting-age population. A value of one corresponds to exactly proportional representation. Larger numbers indicate that a group is over-represented, while values below one indicate that a group is under-represented.

The table indicates that when cities shift to on-cycle elections, the active electorate begins to look more like the overall adult population. Not surprisingly, as column one reveals, white voters are overrepresented in off-cycle elections (a ratio of 1.68). But shifting to on-cycle presidential dates reduces that ratio by 0.30. On-cycle elections don’t lead all the way to proportional participation by race, but they get us much closer. Latinos, also as expected, are greatly underrepresented in off-cycle elections. The Latino share of the population is roughly double the group’s share of voters in off-cycle contests. But when local elections are held concurrently with the presidential contest, Latino representation moves much closer to parity — a ratio of .86 in local contests held the same day as presidential elections.

Effects are even more pronounced in terms of voter age. Older Americans represent more than two times as many voters in off-cycle elections as they do adult city residents. But that overrepresentation is reduced by roughly half in on-cycle contests. Finally, Democrats are generally slightly underrepresented in off-cycle elections (a ratio of .91) but moving to concurrent local elections produces near-parity (a ratio of .98). Additional analysis also reveals significant and substantial effects for class (measured by income and wealth) as well as for other racial and ethnic minority groups (Asian Americans).

While these data are all from one state, nearly identical analysis in Florida also finds that moving to on-cycle elections dramatically alters the composition of the vote. In summary, the shift to on-cycle elections moves us closer to a world where voters begin to look more like the population of city residents.

Where Does Timing Matter Most?

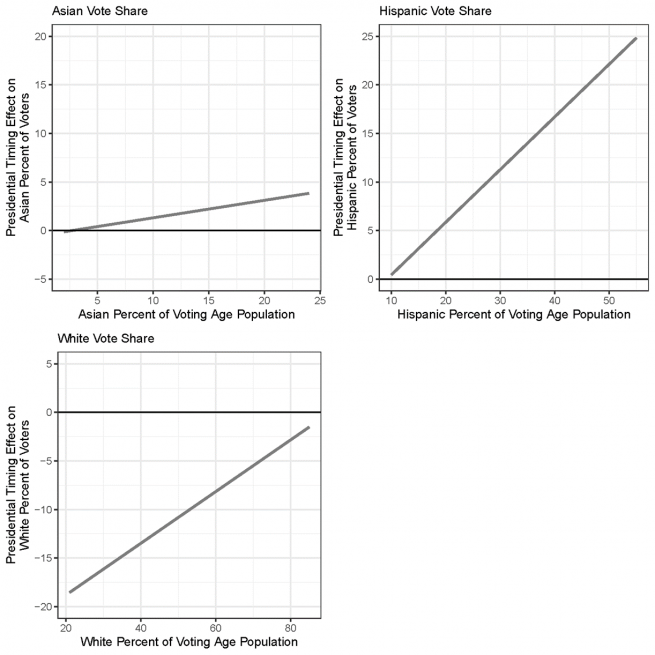

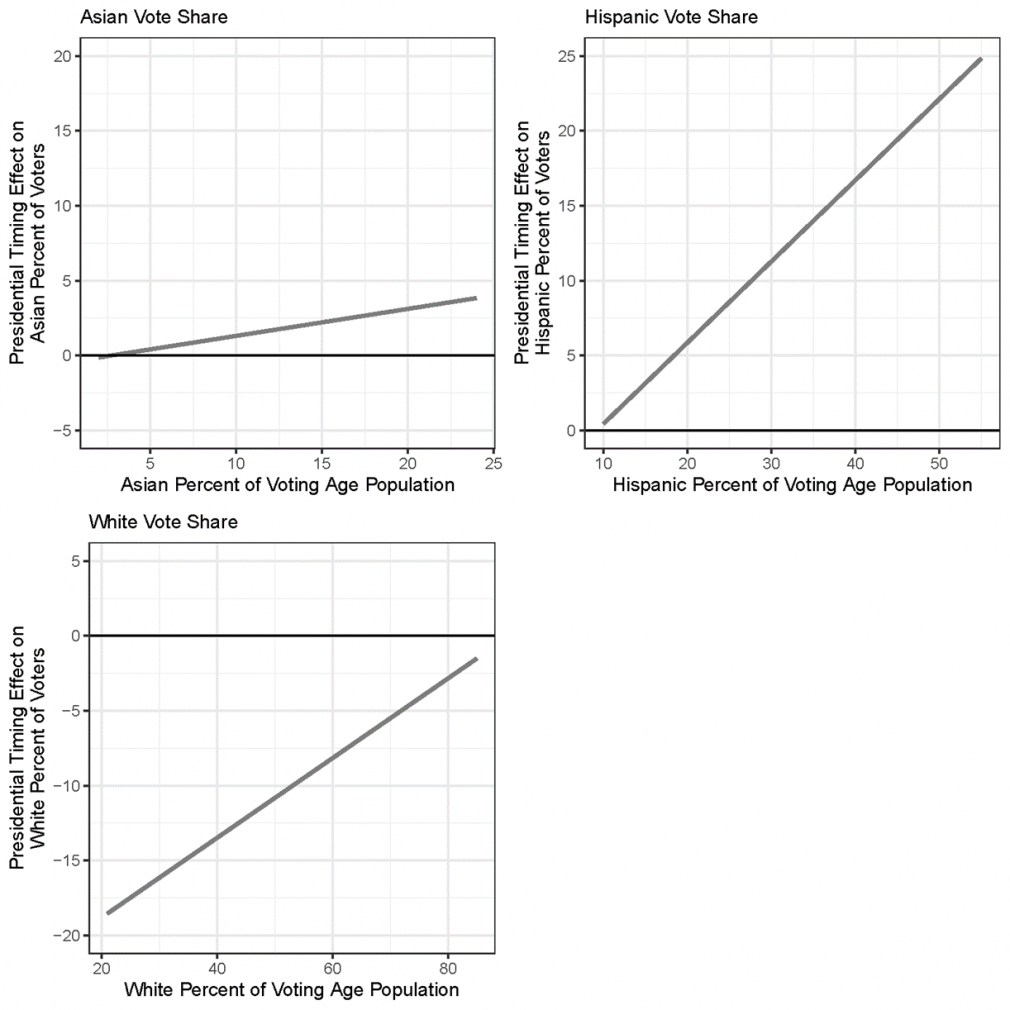

If timing affects voter racial composition, we should see the most pronounced effects in cities where minorities make-up a larger share of the city population. In the figure below we show that this is indeed the case. The figure shows how the predicted effect of election timing varies across cities with different levels of minority population. The figure compares off-cycle to presidential elections.

Significance

We live in a time when the nation is focusing enormous attention on electoral reform. While some efforts limit voter options in the name of preventing fraud, others seek to expand the electorate. As we write this, at least 112 bills expanding voter access are moving through 31 state legislatures and Congress is considering HR1, a major initiative to expand democratic access and equity. Almost as many fraud-related measures are actively being considered or passed. In short, there is a real appetite for electoral reform.

On-cycle elections are a reform that is not only getting increasing attention but also one that could potentially be rapidly expanded around the country. Three states — California, Arizona, and Nevada — have recently passed laws mandating on-cycle elections. At least two others — Washington state and Tennessee — are considering legislation to do the same. Moreover, with surveys showing that the public strongly favors on-cycle elections, widespread timing reform seems quite possible.

For all of these reasons, it is critical that we do more to understand the effects of local election timing. We have shown that moving to on-cycle elections — especially to elections held on the same day as presidential contests — has real potential to alter who participates in local democracy. In California, holding city elections concurrently with statewide and national contests reduces the over-representation of whites and older Americans and, to a smaller extent, the well-off. The voters who typically participate the least and, generally have less of a voice in American democracy, gain the most. These patterns make the move to on-cycle elections well worth considering.

Bibliography

Anzia, Sara. 2013. Timing and Turnout: How Off-Cycle Elections Favor Organized Groups. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Hajnal, Zoltan L. 2010. America’s Uneven Democracy: Turnout, Race, and Representation in City Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Holbrook, Thomas, and Aaron Weinschenk. 2014. “Campaigns, Mobilization, and Turnout in Mayoral Elections.” Political Research Quarterly 67: 42–55.

Kogan, Vladimir, Stéphane Lavertu, and Zachary Peskowitz. 2018. “Election Timing, Electorate Composition, and Policy Outcomes: Evidence from School Districts.” American Journal of Political Science 62: 637–51.