What do we know about vote-by-mail?

Lessons from Wisconsin, North Carolina, and beyond

On April 7th, Wisconsin held their primary elections; a routine process that became controversial given the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. Things did not go entirely as planned.

A joint investigation by the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, PBS, and FRONTLINE found that Wisconsin’s vote-by-mail process buckled in the face of a historic surge in applications and a global pandemic. Some voters never received their ballot; others received two; a few received empty envelopes. These errors, and the lagging returns of late (and now null) ballots, occurred despite the efforts of election officials who worked around the clock for weeks before the fateful day. In the end, many Wisconsin voters made the decision to vote in-person, which raised public health alarms about the potential spread of the COVID-19 virus as a result of polling lines.

Against that backdrop, a broad transition away from in-person voting in favor of voting-by-mail (VBM) might seem like a very bad idea.

Do Americans agree with that conclusion? Some do, but that seems to depend on their political affiliation. The discourse on vote-by-mail has become politically charged, with Democrats often lauding the process and Republicans disparaging it. This divide isn’t just limited to polarization among elites, either. In a recent AP-NORC poll, Americans were asked whether they supported their state conducting elections exclusively by mail. 60% of Democrats supported the policy, while only 37% of Republicans agreed with it. Interestingly, these numbers actually represent an increase in American support for mail-in only voting since 2018, but the party-line is stark.

To some American voters, VBM is old news. Utah and Hawaii both passed legislation to run their elections entirely by mail in 2019. Oregon, Washington, and Colorado have been conducting their elections by mail for years. One key difference: these states have had years to prepare for this policy change. The rest of the country won’t have that luxury, and VBM — as with any system — has its drawbacks even in a perfect situation.

However, as the coronavirus continues to keep physical distance a priority for public health, VBM is a policy well worth examining for the remaining primaries and the November election.

Hard lessons in North Carolina

Let’s start our analysis by acknowledging a fear voiced by many who are skeptical of voting-by-mail: voter fraud.

In the summer of 2019, Republican operative L. McCrae Dowless Jr. was indicted on allegations of voter fraud while working for North Carolina Congressional candidate Mark Harris. Dowless allegedly harvested absentee ballots and fraudulently sent them in, effectively posing as real North Carolinian voters.

The close election, which Harris initially seemed to have won by a mere 905 votes, was called into question after Dowless’ activities were revealed. Through emails taken into evidence by the court, it became apparent that Harris himself had some knowledge of Dowless’ reputation and absentee ballot scheme, at least to an extent. A new election was set; Harris did not run again.

Any election fraud, especially fraud at this scale, should be chilling to voters and politicians of any party — but voter fraud writ large is actually very rare in the United States. Even so, the chances for someone else looking to enact a scheme like this might improve with a VBM system that makes it easier for them to impersonate voters or cast multiple votes. For people very concerned with voter fraud, a move to a VBM-based system seems dangerous and provides avenues for potential political manipulation.

We can see this fear in the news right now, as Republicans accuse Democrats of using vote-by-mail as a partisan tool to affect election outcomes.

Is vote-by-mail partisan?

Although accusations that vote-by-mail will give one political party an upper hand in elections get airtime, there is little evidence to back it up.

In a new working paper, a group of researchers analyzed elections from 1996 to 2008 and found that vote-by-mail increases overall turnout by a modest margin, but does not have an effect on each party’s turnout or vote share. The researchers are also clear, though, that their findings are based on states opting into mail-in systems in less uncertain times, so let’s examine a contemporary example that might end up showing the same pattern: Florida’s 2020 primary.

When Florida held its primary on March 17, local officials were already urging individuals to follow social distancing guidelines and avoid gathering in large groups. How did Florida voters respond? The answer is in the voter file.

Florida’s official primary data is still a work in progress, as it takes time for counties to finalize and report the final voter file, but MIT Election Lab Director Charles Stewart has already written about some initial findings:

- A larger share of Floridians voted by mail in the 2020 presidential primary than the 2016 primary.

- Voters over 60 were most likely to vote by mail out of any other age group.

- Republicans were more likely than Democrats to vote by mail in 2020; there was no partisan difference in 2016.

Florida’s elections were not marred by the same dysfunction as Wisconsin’s. This may be for several reasons. Florida’s primary this year had the lowest turnout recorded of any other Florida primary since 2004, though voting by mail continued to be higher than previous years. There have also been targeted initiatives to increase VBM turnout by the Florida Democratic Party since late 2019, with a specific focus on Black and Latinx voters. This initiative included expanding infrastructure to accommodate more mail ballots on Election Day.

Vote-by-mail challenges and lack of voter trust

Even setting aside the questions of partisanship and fraud, it’s reasonable for voters to express some nervousness about dropping off their ballot at the post office for the first time. While the number of Americans who vote by mail has been steadily growing since 1972, and has grown even more rapidly since 2000, recent examples of chaos (like Wisconsin’s lost ballots), create anxiety for voters about the entire process.

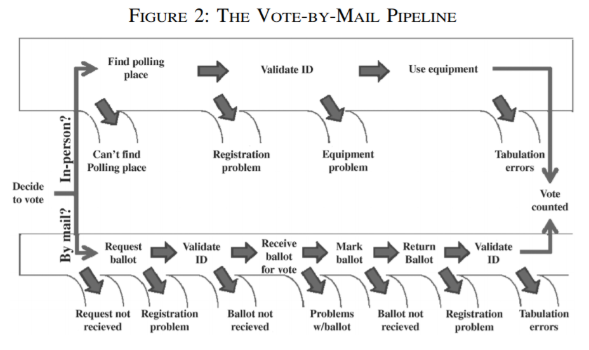

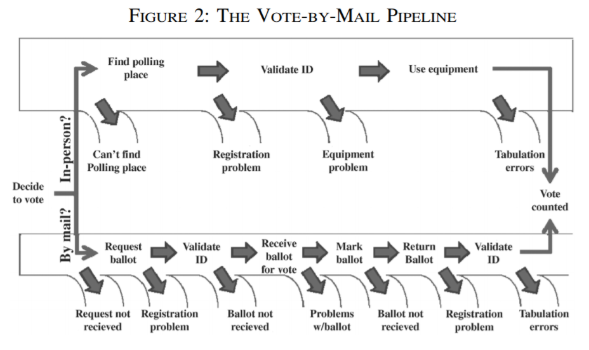

As a voter, it’s easy to think about all the places the VBM process can go awry. After all, when you’re accustomed to handing your ballot directly to a poll worker, you might wonder how to be sure that your vote got to where it needed to go and was counted the way you intended. The below diagram from Professor Charles Stewart’s paper “Losing Votes by Mail” neatly documents the possible shortfalls:

Many of these opportunities for a vote to go awry have to do with the two-step process that many states require for VBM, wherein a voter mails in their application to vote, and then, once that is approved, receives and mails in their ballot. Though very little mail in the United States is truly lost, it can be difficult to track all of these steps reliably. We simply don’t have very good data available on absentee ballots yet, and the quality of reported data we do have often varies wildly depending on the year and state — which makes comparing across years or state lines difficult.

Beyond the data woes of researchers, though, when something goes wrong in the VBM pipeline, it can cause serious issues for voters and election officials. Sometimes, a voter may never be informed that something went wrong; conversely, election officials may never know a voter even applied for a ballot. Voters can become frustrated when their promised ballot never arrives, or when they’re unable to confirm it was counted. Many states, for example, do not inform voters if their ballot wasn’t counted because of a mismatched signature (though some, including Georgia, require election officials to let voters correct their ballot if they find a mismatch).

Yet despite these challenges and uncertainties, the pandemic makes it highly likely that more Americans will request mail-in ballots rather than visiting the polls in person. At the system-level, it seems that proceeding “as normal” may carry dire costs, both for the nation’s healthcare systems and for individual voters. We need to understand both the opportunities and challenges of VBM, and include it in our full toolbox of possible solutions to the problem of carrying out fair, healthy elections.

What should we expect?

No expert can tell us what, exactly, we can expect in the months between now and November, or how badly COVID-19 will affect voters and voting processes. That said, we’ve already seen that in-person voting in Wisconsin has been linked to some coronavirus cases, though there is no evidence of a statewide uptick yet. It’s not unreasonable for us to expect more: in-person voting necessarily requires people to be in close proximity to others for an extended period of time, and therefore carries inherent risks. Voters gathered at polling stations will be in danger (especially older voters, and Black and Latinx voters of all ages, for whom the virus poses a greater risk); so will the Americans who work at the polls, the majority of whom are 61 or older.

While the obstacles for a state trying to implement or scale up vote-by-mail are daunting, states will nevertheless need to prepare for a rise in absentee ballot requests in the run-up to the remaining primaries and general election. Georgia, for example, has seen almost twice the number of absentee ballot requests for the upcoming June 9th primary than either the 2018 midterm (which included a hotly contested gubernatorial election) or the 2016 presidential election.

These preparations will look different for each state. States like Texas, for example, let counties set the majority of election rules and regulations, meaning that galvanizing around a VBM system tailored to the unique circumstances of the coronavirus will occur slowly, if at all. Some voters— including the homeless, and those (such as Native Americans,) who do not have traditional mailing addresses — will find it extremely difficult to vote under the usual rules of vote-by-mail. States will need to consider and implement ways to ensure these voters are able to cast their ballots safely as well.

While those states who vote entirely by mail have had years to prepare and accrue the manpower and technical ability required to pull off an election, the rest of the country will need to scramble to get ready, revamping their administrative capacities at record speed. It is a truly mammoth challenge, but there may be no other option.