Who are Local Election Officials, and What do they Say about Elections?

The MIT Election Data and Science Lab helps highlight new research and interesting ideas in election science, and is a proud co-sponsor of the Election Sciences, Reform, & Administration Conference (ESRA).

Our post today was written by Anita Manion, David Kimball, Paul Gronke, Joseph Anthony, and Adriano Udani, based on their presentation at the 2021 ESRA Conference. The information and opinions expressed in this column represent their own research, and do not necessarily represent the opinions of the MIT Election Lab or MIT.

Local election officials (LEOs) have a diverse and challenging set of responsibilities. These "stewards of democracy" serve voters through their role in managing voter registration, balloting procedures, and engaging in voter education and outreach. They serve candidates, parties, and groups that want ballot access and demand timely and trustworthy election results. And finally, LEOs provide an important and expert voice in discussion and debates about election reform.

Given the central role that LEOs play in so many aspects of the American democratic system, our research takes a close look at the values, beliefs, and opinions that LEOs have about election integrity and reform, and how their opinions differ from the public at large. There are good reasons to expect that LEOs will think about these issues in different ways than the public. LEOs are more experienced and knowledgeable about voting laws and procedures than the average American; so, we would expect that their opinions are more firmly grounded. Because the public is less aware of election policies, they may be more prone to influence by rhetoric from elites (including politicians, party leaders, and organized interests). At the same time, it is not clear how much the expertise that a local official gains from conducting local elections insulates them from rhetoric about national election integrity or how LEOs formulate views about election procedures that aren’t in place in their state. In short, our research tries to identify ways that LEO values, beliefs, and opinions are distinct from the public at large, and ways that they think much like the public that they serve.

Do LEOs Look Like the Public?

While demography is not destiny, we start by highlighting some fairly substantial demographic differences between LEOs and the public. The demographic characteristics of a population of agency managers (LEOs) will not match the mass public, and this may contribute to differences in their political opinions.

Table 1 compares the public sample and the LEO sample on gender, race, education, income, age, and partisanship. Local officials are older, whiter, and more likely to be female than the average member of the public. These differences are especially pronounced among officials from small and medium-sized jurisdictions. LEOs are slightly wealthier and more educated than the public, but these differences are driven by officials in large and medium-sized jurisdictions. Consistent with the politics of more populous urban areas, LEOs in large jurisdictions are less likely to be Republican than officials in smaller jurisdictions and less likely than the general public. We also note LEOs are overwhelmingly white.

Table 1: Demographic Comparisons of LEOs and the Mass Public

|

Demographic |

Public |

LEOs |

<25,000* |

25,000 to 250,000* |

>250,000* |

|

Female |

51% |

81% |

85% |

68% |

47% |

|

White |

69% |

94% |

94% |

93% |

85% |

|

College |

41% |

50% |

47% |

62% |

82% |

|

$50,000 or more |

51% |

45% |

37% |

84% |

95% |

|

50 or older |

49% |

74% |

75% |

66% |

61% |

|

Republican |

40% |

44% |

46% |

40% |

17% |

|

Elected |

- |

57% |

61% |

35% |

18% |

LEOs Have More Positive Views of Election Integrity

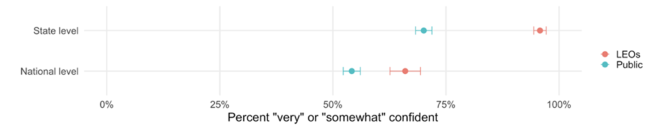

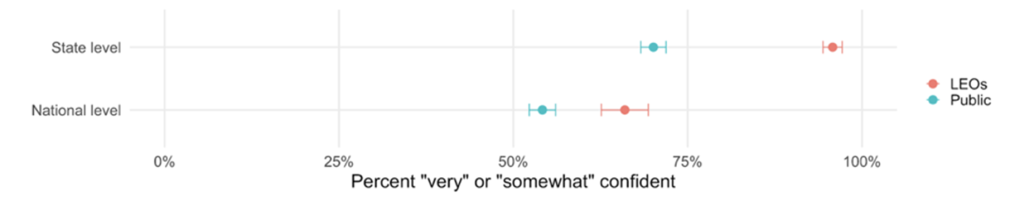

LEOs consistently offer more positive assessments of elections than does the public. As Figure 1 shows, LEOs have more confidence that ballots are counted as intended, but like the public, LEOs are more confident about the vote count in their state than nationwide. The positivity gap is larger at the state level, which is what we would expect since LEOs play a critical role in counting votes in their own state.

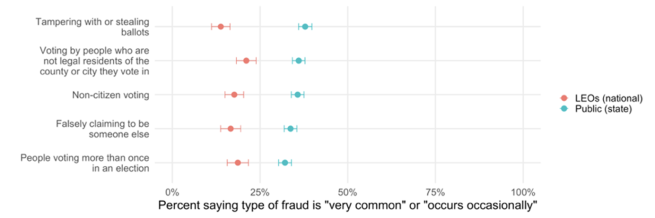

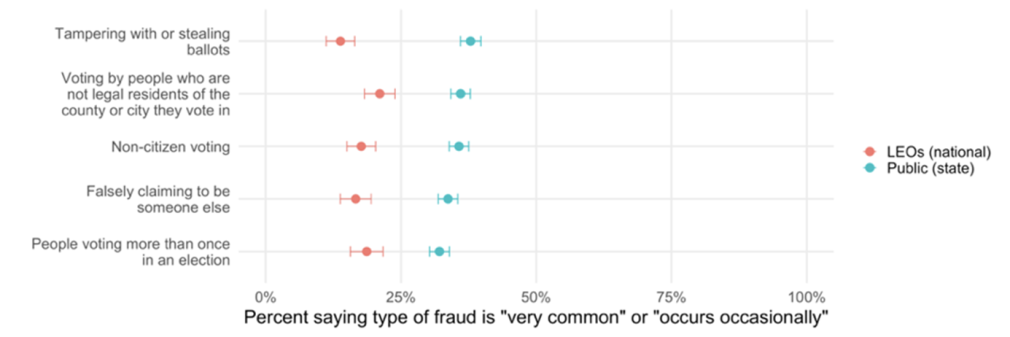

The same pattern emerges when we compare beliefs about voter fraud (Figure 2). In this case, there was a key difference in the question wording: the LEO survey asked about voter fraud nationwide while the mass public was asked about voter fraud in their state. But given what we just saw in Figure 1 – lower evaluations at the national level – we would expect that the mass public would think there is less voter fraud (in their state) than LEOs think there is at the national level. Instead, our survey shows that LEOs believe that voter fraud is less frequent than the public. Among the public, between 32-38% believe that each type of fraud is “very common” or “occurs occasionally” in their state, while the comparable figures for the LEO sample are between 13-21% nationally.

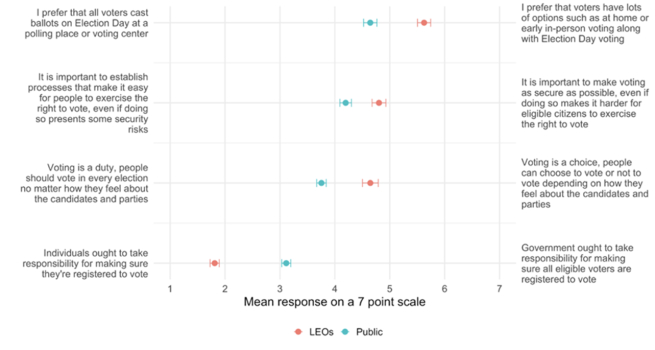

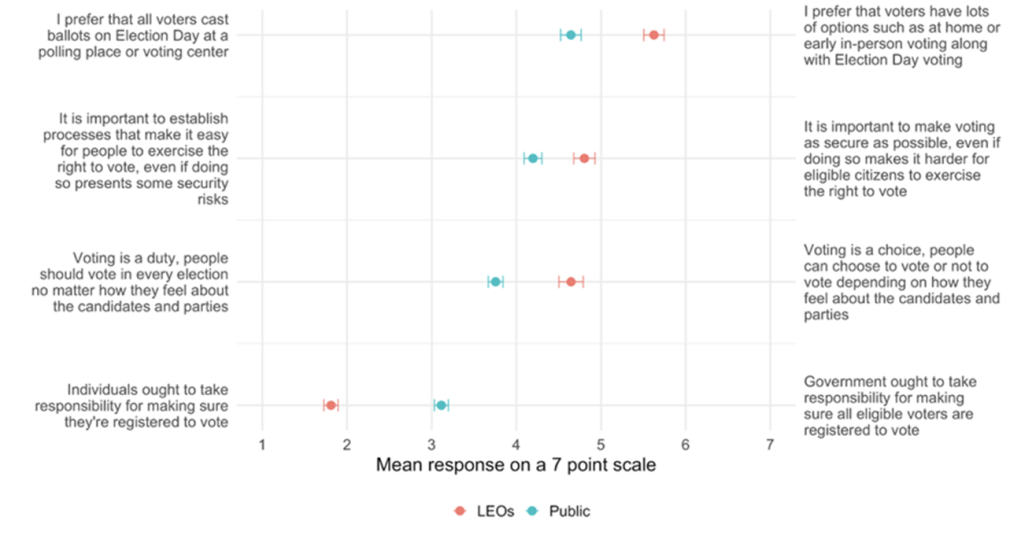

LEOs Make Clearer Distinctions Between Competing Voting Values

We included in our surveys four questions that reflect competing and contending values that often crop up in debates of election integrity, such as access vs. security or voting in person vs. voting at home. LEOs occupy positions nearer to the endpoints on these questions than does the public, shown in Figure 4. LEOs are more likely to endorse voters having “more options”, to prioritize security over access, to describe voting as a choice not a duty, and to assign the primary responsibility of registration to the citizen rather than the government. We believe that LEOs’ knowledge and experience with election administration explains why they tend to have stronger views when asked to choose between competing viewpoints on voting.

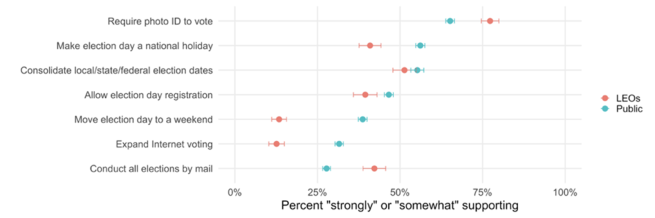

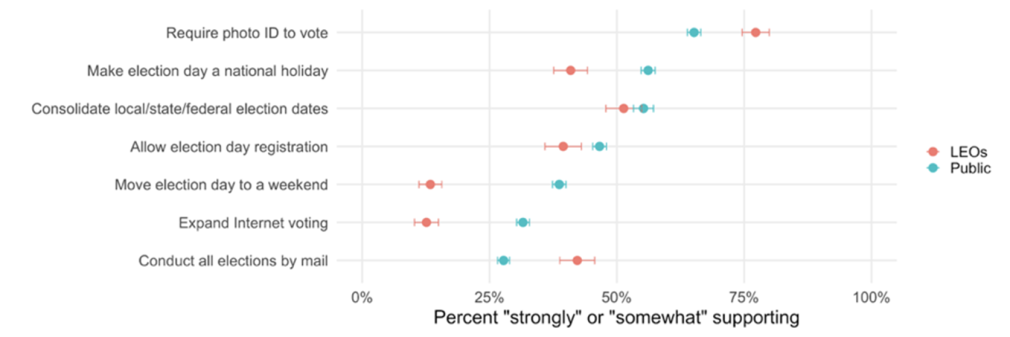

LEOs Are More Skeptical of Some Election Reforms

Finally, when asked about some commonly proposed election reforms, LEOs are more reluctant to endorse changes than is the public. Election Day registration, making Election Day a holiday or moving it to a weekend, and Internet voting all receive more support from the public. That is not surprising, as these reforms would require significant resources to administer as an election official, and increased administrative burden is linked to opinions toward policy reforms. LEO opposition to Election Day registration may also reflect the strong belief among officials that registration should be the responsibility of individual voters. LEO opposition to internet voting and moving elections to a weekend are particularly strong – more than 80% of LEOs in our survey expressed opposition to both.

In contrast, LEOs express stronger support for voter ID than the public (over three-quarters of LEOs strongly or somewhat support, compared to 65% of the public) and for conducting all elections by mail (just over 40% of LEOs support compared to just over 25% of the public). Both of these reforms have become drawn into polarized partisan debates over elections, and we will explore in future research how much partisanship explains these patterns among LEOs and among the public.

Why Does this Matter?

As we noted at the outset, LEOs have an important role to play in informing political debates over election integrity and reform, and they should, since they are the experts in election administration. But we also recognize that LEOs are a large and diverse set of administrators, living and working in more than 8,000 large, medium, and small jurisdictions spread across 50 states and the District of Columbia with 50 different election codes and 50 different election ecosystems.

Our research compares opinions about elections between LEOs and the mass public. We think these comparisons are important in the current political environment where debates over voter fraud and election reform frequently divide along party lines. Election officials are often forced to respond to claims of voter fraud or proposed changes to election laws, and knowing how LEOs are similar to and differ from the mass public may provide new insights into the role that election administration and public opinion play in fostering trust and legitimacy in the American election system and help us better understand the decision-making processes used by LEOs. This may help inform efforts to counter misinformation about election issues.