Who Votes Provisionally and Why?

The MIT Election Data and Science Lab helps highlight new research and interesting ideas in election science. Thessalia Merivaki and Daniel A. Smith recently presented a paper at the 2018 annual meeting of the Midwest Political Science Association entitled, “Who are Provisional Voters? Evidence from North Carolina.” Here, Professors Merivaki and Smith summarize their analysis from that paper.

Voting in the United States is often conceptualized as a two-step process. Except for North Dakota, all states require prospective voters to be registered to vote prior to Election Day. Once registered, voters may cast their ballot on Election Day or vote early, either in-person or by mail. While early voting is becoming the method of choice in an increasing number of states, as the Election Assistance Commission (EAC) reports, a substantial portion of the electorate still votes in-person on Election Day at their local polling station.

The process of registering to vote is unquestionably one of the biggest hurdles prospective voters must jump before participating in an upcoming election. Individuals have to submit a voter registration application within a state-mandated deadline, which is then verified and processed by local election officials. If the applicant satisfies all the eligibility requirements in her state and county of residence, she should successfully be added to the voter rolls and will be permitted to cast a regular ballot.

Every election year, though, there are numerous stories about how some voters are not able to cast their vote, often because their voter registration and/or eligibility status was not verified. A recent example from the November 2017 state legislative elections in Virginia is a useful illustration. Hundreds of voters were erroneously assigned to the wrong state legislative district; when they showed up to vote, they were informed that they were not eligible to vote in that particular jurisdiction, and were provided with a provisional ballot instead. Many Kansas voters experienced similar problems prior to the 2016 General Election; one-third of the more than 40,000 voters who cast provisional ballots had their votes invalidated because their voter registration information could not be verified by local poll workers.

Administrative errors during the registration process can account for many of these incidents. Such errors have important implications concerning the fair and equal treatment of voters, especially if certain voters are disproportionately more likely to have their eligibility questioned at the polls and have their provisional vote rejected.

Administrative errors, however, do not tell the whole story. Those who show up in person to cast their vote may still be required to cast a provisional ballot because there is no record that they are registered. The Help America Vote Act (HAVA) of 2002 explicitly ensures that prospective voters may not be turned away from the polls if they are not registered or lack proper identification; instead, they are offered the option of casting a provisional ballot, which will be counted if the voter’s eligibility is later verified by a canvassing board. Designed as a failsafe to protect a citizen’s right to vote, provisional voting has ensured that thousands of individuals who face issues when trying to cast their ballot were able to vote. Indeed, in the 2016 General Election, the EAC reported that 71 percent of all provisional ballots cast across the states were verified, either partially or in full.

At first blush, the high acceptance rates of provisional ballots should be reassuring. But upon further reflection, the fact that over two-thirds of provisional ballots cast nationwide are ultimately accepted raises the question why some eligible voters were stymied in the first place from casting a regular ballot. Furthermore, scholars know relatively little about the reasons why some 2.5 million voters in 2016 were required to cast a provisional vote, and why 29 percent of these provisional ballots were later rejected. Is the rejection of provisional ballots due to administrative errors? Is it because the prospective voter did not show proper identification or because she did not update her voter registration? Is it because she registered to vote too close to the voter registration deadline, or immediately after the cutoff date, and her voter registration was not processed in time for her application to appear on the voter registration list? Is it because the voter was properly (or improperly) stricken from the rolls, or has already voted, either in person or by mail?

Provisional Ballots: Evidence from North Carolina’s 2016 General Election

Although the national rates of provisional ballots cast and rejected are relatively low, there is considerable sub-national variation across the states, suggesting either that the administration of provisional ballots is not systematic across states, or that the composition of individuals who might be asked to cast a provisional ballot varies across states. To investigate the issues associated with casting and verifying a provisional ballot, as well as understand who is more prone to vote provisionally, we analyze individual-level data from North Carolina’s provisional voters in the 2016 presidential election.

North Carolina is a particularly interesting state to study due to a controversial election law that the state legislature adopted in 2013, which prohibited out-of-precinct ballots from being counted as valid. In 2016, state election officials reported to the EAC that due to ongoing litigation of several provisions of this law, out-of-precinct ballots would be partially accepted. Although North Carolina allows voters to register to vote during its early voting period, it does not permit otherwise eligible individuals to register on Election Day. Under HAVA, unregistered individuals who show up to the polls on Election Day in North Carolina are still permitted to cast a provisional ballot; presumably, however, those ballots will be rejected.

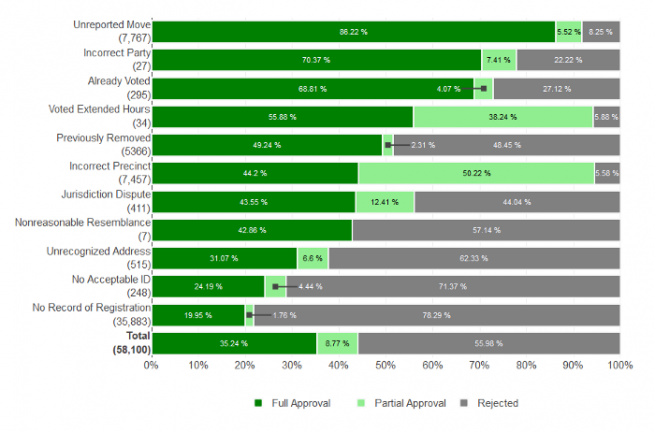

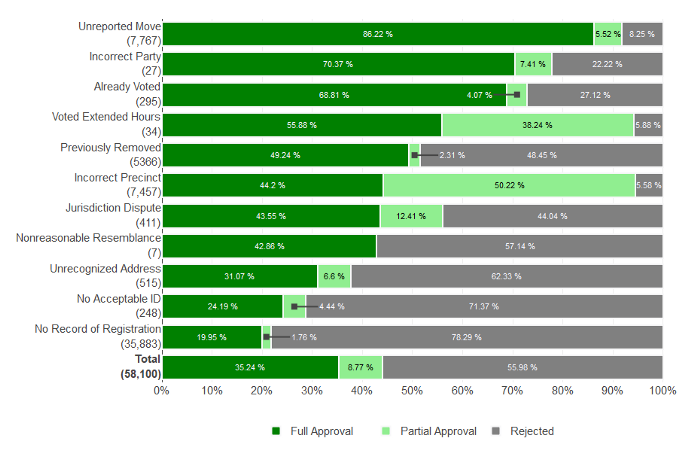

In 2016 in North Carolina, 96% of the 60,643 provisional ballots cast were by those who showed up to vote on Election Day. Approximately 56% of these provisional ballots were then rejected. As the graph below shows, over half of all provisional ballots (35,883, or approximately 62%) were cast because there was “no record of registration” of the individual who showed up at the polls. However, approximately 22% (7,790) of provisional voters had their ballots accepted, either partially or full, suggesting that their voter registration information was later verified by local elections administrators. Aside from the “no record of registration” category, North Carolina offers ten additional reasons why a provisional ballot should be issued, such as problems with the voter’s address (“unrecognized address,” “unreported move”), their precinct (“incorrect precinct,” “jurisdiction dispute”), registration eligibility (“previously removed,” “no acceptable ID”), or if the voter already voted.

Reasons for Election Day provisional ballots cast in the 2016 North Carolina General Election

A deeper look into the number of accepted provisional ballots cast by voters who were found to be removed from the voter rolls (“previously removed”) raises an interesting question about maintaining records of active, inactive, and removed voters across the states. Over half (2,766 of 5,366) of all North Carolina voters who were required to cast a provisional ballot because they were “previously removed” eventually had their ballots accepted in full or partially. It is not clear whether these voters were erroneously removed from the rolls and therefore were not included among the active and inactive voters listed on poll books. The fact that half of these voters ended up having their vote counted indicates that provisional ballots do serve their purpose as a failsafe when the voter’s registration is questioned at the polls.

Additionally, the two-thirds rejection rate of the 248 provisional ballots cast by individuals who did not produce an acceptable form of identification highlights some of the problems with the implementation of the state’s voter identification law. Although North Carolina’s voter identification law was struck down by a federal court in July 2016, first-time voters were still required to show photo identification at the polls, under the Help America Vote Act (HAVA) provisions. According to the North Carolina State Board of Elections website, voters who did not have an acceptable photo ID at the polls were instructed to go to the county board of elections and present a valid ID “before the date set for the county canvass of the election in which they voter provisionally.”

Jurisdiction-based issues remain at the heart of provisional voting. As the graph above shows, many voters were required to vote provisionally because they showed up at the wrong precinct (7,547), had recently moved but did not update their information (7,767), provided an address that was deemed unrecognizable (515), or had their residency eligibility disputed at the polls (411). Out-of-precinct provisional ballots accounted for only 13 percent of all provisional ballots cast across North Carolina’s 100 counties. The majority of these ballots were accepted, partially or in full; however, 5.6 percent of these ballots were rejected, which raises some concerns about how local election administrators process provisional ballots. Of the 7,767 voters who had an “unreported move” to a new jurisdiction and who were required to cast a provisional ballot, the majority (91.7%) had their ballots accepted in full or partially.

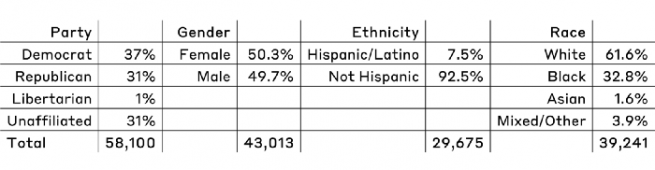

The partisan and demographic make-up of Election Day provisional voters in the 2016 North Carolina General Election.

What do we know about the demographics of those who cast a provisional ballot on Election Day in North Carolina in 2016? As the table above shows, the data reported by the North Carolina State Board of Elections does not include the full demographics of all the 58,100 provisional voters. The most complete information concerns the party registration of provisional voters, of which there was an even distribution of Republican and Unaffiliated registrants, and a slight plurality of Democratic registrants. The subsample of provisional voters for which demographic information was recorded shows that they were predominantly white and non-Hispanic, with an even split between males and females. Of course, when considered as a percentage of their overall share of registered voters in North Carolina, black, Hispanic, and Asian voters were disproportionately more likely to have cast a provisional ballot in the election.

Unfortunately, we know little about the more than 14,000 provisional voters for whom we do not have any gender, racial, or ethnic data. We do know that 56 percent of these voters had their provisional votes rejected, but that 35 percent ended up having their ballots accepted in full. This raises an additional question as to how provisional voters are processed at the polls as well as what information is sufficient for local election officials to report regarding these voters.

Lessons learned and questions unanswered

Our individual-level analysis of Election Day provisional voters in North Carolina uncovers many of the challenges that some voters face at the polls. As the data show, the primary reason voters were required to cast a provisional vote in 2016 was because there was no record of the individual’s registration in the poll books. This does not necessarily mean that these individuals were not registered to vote. As we show in Figure 1, approximately 22 percent of these voters had their provisional ballots accepted partially or in full. What is more, 51.5 percent of provisional voters who were previously removed had their votes accepted in full or partially. The fact that voters whose information did not appear on the poll books in their respective jurisdiction were able to have their ballot accepted indicates that provisional voting does indeed constitute a failsafe mechanism, as HAVA intended.

At the same time, our findings strongly suggest that provisional voting is linked to a county’s voter list maintenance practices. Why were these voters not on their precinct’s rolls if they were registered to vote? There is certainly more to investigate with regard to the high percentage of provisional ballots rejected across counties because the voter was apparently not properly registered, had an unrecognized address, or had been previously removed from the voter rolls. More investigation is needed to determine whether provisional votes are being denied due to voter error when registering to vote, the updating of voter information prior to an election, or local election administrators and poll workers failing to comply with federal and state regulations.