Since the Help America Vote Act (HAVA) became law in 2002, all states have been required to use provisional ballots. The only exception is states that offered same-day registration when the National Voter Registration Act was enacted in 1993, and even most of these states have found them useful in certain situations.

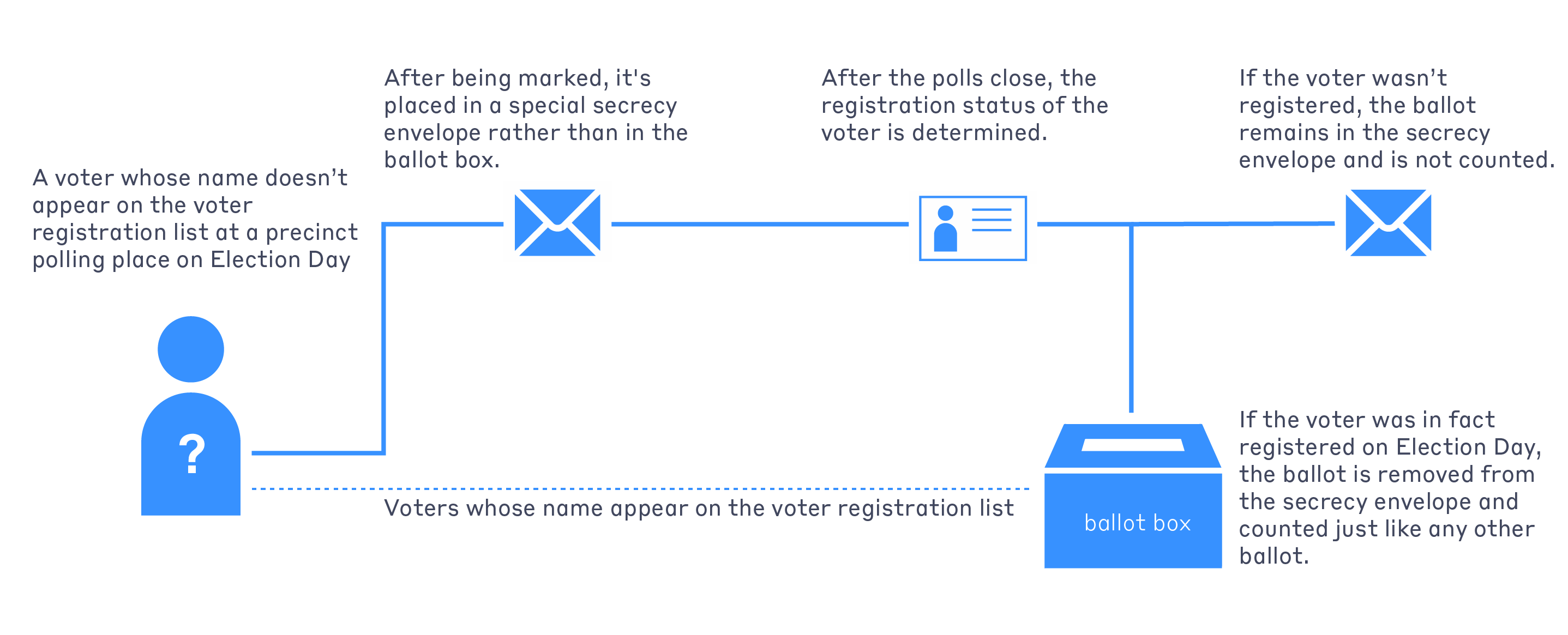

In its most basic form, a provisional ballot works like this: A voter whose name doesn’t appear on the voter registration list at a precinct polling place on Election Day—but who believes she or he is, in fact, registered—may be offered a provisional ballot. After being marked, it's placed in a special secrecy envelope rather than in the ballot box. After the polls close, the registration status of the voter is determined. If the voter was in fact registered in that precinct on Election Day, the ballot is removed from the secrecy envelope and counted just like any other ballot. If the voter wasn’t registered, the ballot remains in the secrecy envelope and is not counted.

How provisional ballots are implemented varies significantly across the states, reflecting differences in both state laws and cultural practices. While provisional ballots are intended as a method to ensure that no voter is turned away from the polls when there are questions about registration, there is still controversy over whether provisional ballot use is a positive or negative factor in election administration.

This explainer was last updated on December 18, 2025.

Before and after HAVA

By 2000, only 17 states and the District of Columbia had some form of provisional balloting. Another seven states had voter registration systems that made provisional ballots irrelevant - either because they had Election Day Registration (EDR) or no voter registration at all. Evidence that hundreds of thousands of voters were turned away at the polls in 2000 because of voter registration errors helped pave the way for a section within the 2002 Help America Vote Act (HAVA) that mandated states adopt provisional balloting unless EDR made them irrelevant.

At the time of HAVA's passage, there was no consensus among the states about how provisional ballots should be implemented. An important question about provisional ballots that varied among the states was, and continues to be, whether to count a provisional ballot if the voter is registered to vote in the jurisdiction but shows up to vote at the wrong precinct. Most states reject provisional ballots in this situation. The states that do count "out-of-precinct" provisional ballots will only count votes cast in the wrong precinct for offices that the voter was eligible to vote for in the correct precinct.

A second major policy choice is how aggressively to give out provisional ballots, and whether to encourage their use as a means to record voters' address changes on Election Day. Allowing provisional ballots to be used for this purpose makes address changes more convenient for voters, but it increases paperwork and may increase the likelihood that a vote will not be counted because of a clerical error.

Current usage

According to the 2024 Election Administration and Voting Survey compiled by the U.S. Election Assistance Commission, approximately 1,736,209 provisional ballots were issued in the 2024 federal election; approximately 1,281,399 were counted, at least in part, and approximately 436,258 were rejected. These 1,736,209 ballots accounted for 0.87% of all votes counted in the 2024 election. The 436,258 rejected provisional ballots amounted to 0.29% of the ballots counted.

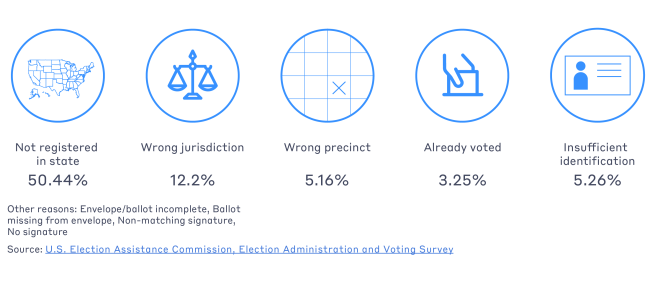

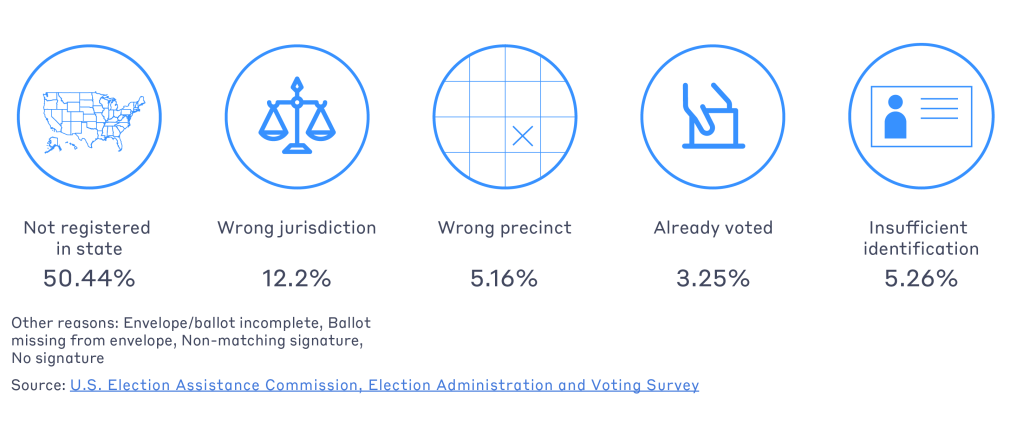

A plurality of the rejected provisional ballots (about 50 percent, down from 51 percent in 2020) were not counted because the voter was not registered on the voter list in that state. The second and third most common reasons provisional ballots were rejected were that the voter was registered in another jurisdiction in the state, or that the voter had insufficient or incorrect information. Other less frequent reasons for provisional ballot rejections included the voter voting in the wrong precinct in the correct jurisdiction, the voter having already voted, and situations where the signature on the provisional ballot application did not match the registration record on file.

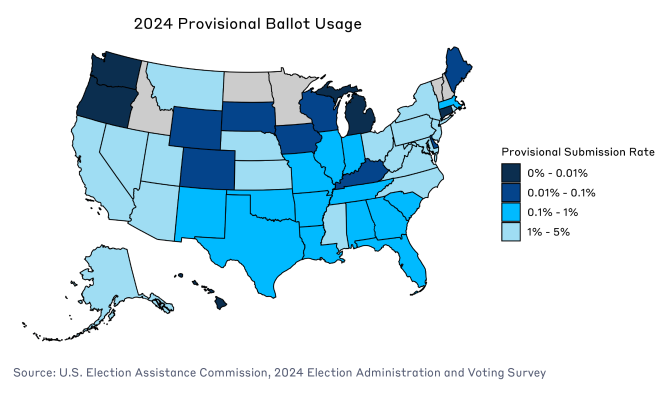

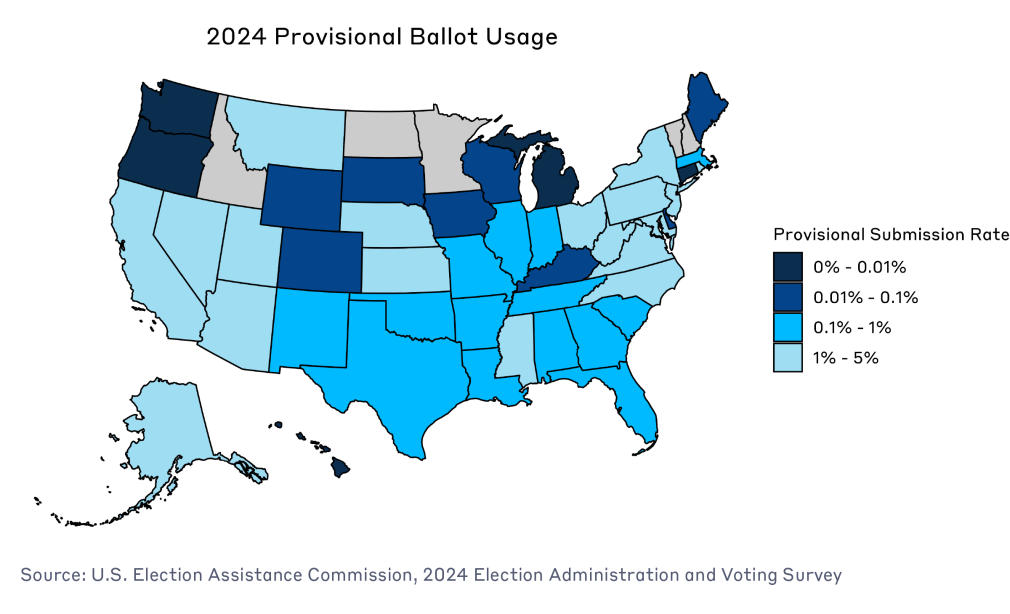

There is significant variability across the states in provisional ballot rejection rates. As seen in the figure below, leaving aside the states that are not required to use provisional ballots, the percentage of voters who submitted a provisional ballot in 2024 ranged from near zero to just below 5%. (The lowest proportion was Michigan, with less than 0.01% provisional ballot usage; the highest was 4.95% in Maryland.)

Previously, one of the strongest predictors of the number of provisional ballots a state issued was whether the state used provisional ballots before HAVA. In 2016, the average provisional ballot distribution rate was 2.0% in states that used provisional ballots before HAVA, but only 0.69% in states that adopted provisional ballots after HAVA. Now, the gap has narrowed as provisional ballot distribution rates have plummeted.

While the 2024 distribution rate is 0.74% in states that adopted provisional voting after HAVA, it’s higher—1.51%—in the original (pre-HAVA) provisional voting states. One contributor to this difference is that many of the states with the greatest provisional ballot usage rates are also states with permanent absentee ballot lists. In these states, if a voter who is on the permanent absentee ballot list shows up on Election Day to vote, the voter is required to cast a provisional ballot that will be checked to ensure that they have not already cast an absentee ballot that is still in the mail.

At the local level, variability in the distribution of provisional ballots is associated with demographics and political factors. Jurisdictions with younger, more mobile, and more minority voters distribute provisional ballots at higher rates. In addition, a greater number of provisional ballots are distributed in presidential election years than in midterm elections.

Are provisional ballots good?

It stands to reason that having a fail-safe mechanism to protect voters against registration errors is a positive provision of election administration. Presumably, the 1,281,399 provisional ballots that were counted in 2024 represent 1,281,399 potential “lost votes”—that is, valid votes that would not have been recorded without a system for provisional ballots through no fault of the voter.

However, some voting rights advocates have argued that the availability of provisional ballots makes it too easy for local jurisdictions to shirk their efforts to maintain accurate voter lists. Processing provisional ballots is subject to clerical errors, so there is at least a small chance that any provisional ballot that should be counted will be rejected for reasons unrelated to whether someone was actually registered. Furthermore, a provisional ballot given to a registered voter who has shown up in the wrong precinct will usually not be counted at all. A question that arises in such cases is whether poll workers should be more insistent that “wrong-precinct voters” go to the correct precinct, rather than issue ballots that will not be counted.

Finally, because provisional ballots are processed after elections, they are one form of ballot (absentee ballots being the other) that can become the target of litigation in the event of a recount. In states with a large number of provisional ballots, even if the rejection rate is typically low, the existence of provisional ballots becomes an easy target of controversy during a recount.