This explainer was last updated on September 16, 2021.

The Process, Explained

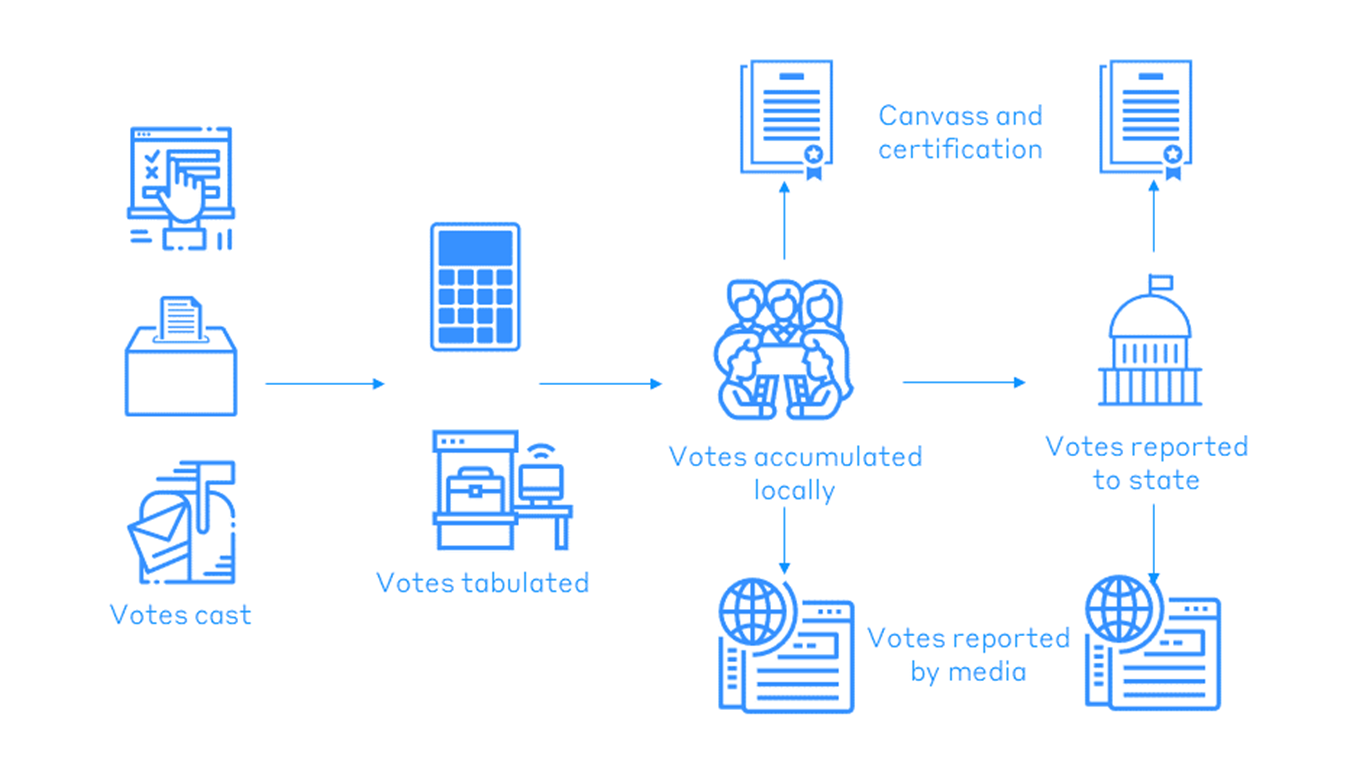

After voters have cast their ballots, election return reporting can be divided into five parts:

- Tabulation of cast ballots

- Accumulation and reporting of results to the local election office

- Reporting of results to the state

- Reporting the results to the public

- Canvassing and certification

Tabulating Votes

Once voters have marked their ballots, they must be counted, or tabulated. Where ballots are tabulated depends on the technology used by voters and certain process choices made by election administrators. A small number of ballots are still counted by hand; they are typically counted in the polling place immediately after the polls have closed by precinct workers. Ballots that have been marked electronically have been stored on the voting machine, which is a type of computer. They are counted by the software on the computer and recorded on a memory device, such as a smart card. A paper record, resembling an adding machine tape, is also usually printed out.

Most ballots are tabulated by scanners, in one of two ways. Ballots are most often scanned in the precinct when the voter places the ballot in the ballot box. In this case, ballots are also counted by software in the scanner, much like what happens with purely electronic machines. In other places, ballots are placed in a ballot box without being scanned and then taken to a central (county or municipality) counting facility once the polls are closed to be scanned and tabulated.

Accumulating Votes Locally

Once votes have been tabulated, they must be aggregated, or accumulated, at the local level. Except for the small number of places that still count ballots by hand, this accumulation occurs using computerized equipment. Smart cards from the counting devices — scanners and electronic machines — are inserted into computers that upload the results into the “election management system” (EMS).

The EMS can be thought of as a database that keeps track of the number of votes received by each candidate in each precinct of that jurisdiction. It can also keep track of other related information, such as the identity of precincts that have yet to report their election results, to help make sure that all votes are counted.

Reporting Votes to the State

Except for purely local elections, local election jurisdictions are responsible for reporting their election results to the state. This can happen either by paper, mail or courier, or electronically.

Reporting the Results to the Public

Election returns are reported to the public at various points in the process. Results are typically posted outside the doorway of the polling place once the counting is finished and before the results are reported to the central election office. Most local voters, though, learn of election results when the precinct returns are reported to the central office; the central office then distributes those results to the public, increasingly using a webpage. When the local jurisdiction reports its initial election returns to the state, the state elections department will in turn make those returns available to the public, also typically using the Internet.

Relatively few members of the general public learn directly of these initial election returns by reading the machine tape pasted to the door of the public place or visiting official websites. Instead, they rely on media reports of election returns. Local, state, and national media sources of all types take the returns issued by election authorities and report them to readers. The most well-known of these media reports are based on information gathered and distributed by two organizations, the Associated Press and the National Election Pool.

Canvassing and Certifying Results

The initial election returns reported to the public are unofficial. They are reported to provide transparency to the process and to prepare everyone, from voters to candidates, for what comes next. Although vote counting on election night is very accurate, it is imperfect and incomplete. To ensure its accuracy, local election authorities have a process, called canvassing, which is described by the U.S. Election Assistance Commission as

[accounting] for every ballot cast and to ensur[ing] that each valid vote is included in the official results. For an election official, the canvass means aggregating or confirming every valid ballot cast and counted—absentee, early voting, Election Day, provisional, challenged, and uniformed and overseas citizen. The canvass enables an election official to resolve discrepancies, correct errors, and take any remedial actions necessary to ensure completeness and accuracy before certifying the election.

Most typically, a group of officials serves as the canvassing board, although the name varies across the states. This board formally reviews all the records that were produced in the election. They will usually check to see, for instance, that the number of ballots that were distributed by clerks in a precinct on Election Day equals the number of votes cast plus the number of ballots that were spoiled by voters. If the two sides of this equation do not balance, the board figures out why and makes the necessary corrections.

The election canvass can be thought of as the equivalent of balancing a checkbook. Checkbooks are balanced by checking that all the additions and subtractions in the checkbook are consistent with the bank’s records. If not, then the reason is investigated and corrected. The same is true for the canvass. If the number of ballots distributed and returned balance — not only for individual precincts, but across all precincts, and not only for Election Day but for all modes of voting — the board can be certain of the result.

Because the canvass almost always finds and resolves discrepancies along the way, the election night results first reported will be changed to reflect the most accurate information. An interesting window into the canvassing process is provided by the Virginia Board of Elections, which has a website that accounts for all changes to vote totals in the canvassing process.

Once the canvassing board is satisfied that all ballots have been accounted for and properly counted, they certify the results, which makes them official. Those certified results are then communicated to the state, where an analogous canvassing board meets to certify the results for the entire state. If the state board believes something is amiss with local results, they may send the local certification back to the locality to be corrected; state canvassing boards rarely, if ever, redo the canvass of a local election department themselves.

Reporting Speed

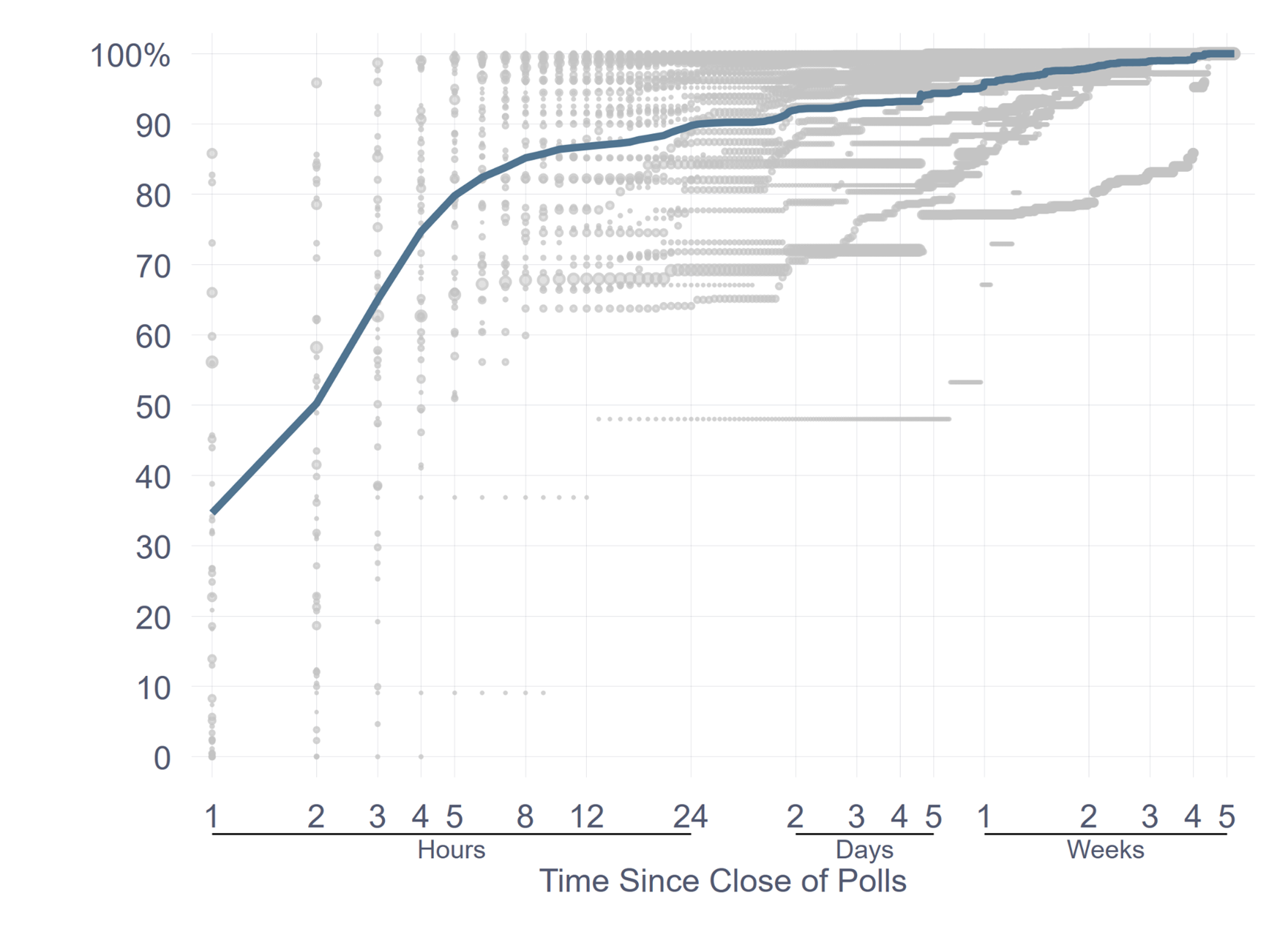

It takes time to count ballots. The question of whether the growth of absentee voting in 2020 would slow down the vote count was highlighted in that election. Analysis performed based on the real-time reports provided by the National Election Pool and certain state ENR websites reveals that states reported their votes at different rates, and that policies related to absentee voting had an important influence on that speed. Figure 1 shows how quickly all the states reported their votes in 2020.

Data source: National Election Pool via the New York Times.

Note: The time scale on the x-axis is logarithmic.

The solid line shows the percentage of the eventual nationwide popular vote that had been reported each hour. For instance, one hour after polls closed in all the states, 35 percent of all votes had been counted; an hour later, that had risen to 50 percent. The circles show the percentages for each state, with the size of the circles proportional to the total popular votes eventually reported. In the first hour, Florida, Oregon, and Washington had reported over 80 percent of all their votes, whereas six states (Alaska, Airzona, Hawaii, Idaho, Maryland, and Nevada) and D.C. had reported none. At the twenty-four hour mark 90 percent of the national popular vote had been counted; 35 states had reported at least 90 percent of their vote, with only one (Alaska) reporting less than half. It took three weeks for 99 percent of the nation’s popular vote to be counted, at which point 29 states had completed their count and only Kansas (97 percent) and New York (83 percent) were at less than 99 percent.

As a general matter, policies related to absentee ballots played a major role in influencing how quickly states reported their election results in the first few days following the election. The slowest states were those that had large numbers of mail ballots, prohibited localities from processing mail ballots before Election Day, and allowed mail ballots to arrive after Election Day (so long as they were postmarked on or before Election Day).

The Blue Shift

In addition to reporting speed, another issue related to vote tabulation is the partisan trends in the total as vote-counting proceeds. Law professor Edward Foley has noted that since the early 2000s, votes for Republican presidential candidates have tended to be counted earlier than votes for Democratic candidates. This has resulted in a “blue shift” in vote margins, starting immediately after Election Day and lasting until all the votes are finally canvassed. This blue shift pattern is such that once the lion’s share of the vote has been counted in the first 24 hours after polls have closed, the remaining votes are typically so overwhelmingly Democratic that vote totals shift perceptibly over the remaining days and weeks.

This pattern has been shown to be due to two major reasons. The first is that counties dominated by the Republican Party tend to be smaller than counties dominated by the Democratic Party. Because the smaller counties complete their counting faster than large counties, the last votes to be reported to the public tend to be more Democratic. The second is that some voting methods that are slow to count tend to be dominated by Democratic voters. One of those methods is provisional ballots, which are not counted until several days after Election Day. In 2020, Democrats also were more likely to vote absentee, which took longer to finish counting than votes cast in person.

Suggested Reading

Kerevel, Yann and Lonna Rae Atkeson. 2012. “Counting the Ballots: A Comparison of Machine and Hand Counts in New Mexico.” in, Confirming Elections: Creating Confidence and Integrity through Election Auditing, ed. R. Michael Alvarez, Lonna Rae Atkeson, and Thad E. Hall. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.