Supporters of more stringent voter ID requirements argue that these will deter voter fraud and instill confidence in the integrity of the electoral process. Opponents argue that voter fraud is extremely rare, so the only effect of strict ID requirements is to raise the barriers to voting in ways that disproportionately affect citizens of low socioeconomic status.

The recent increase in strict voter ID requirements has led to several lawsuits alleging racial discrimination. Similarly, the rise of voter ID laws has led to an increase in scholarly research into the effects of these laws on voter turnout.

This explainer was last updated on June 10, 2021.

Current requirements

Under the 2002 Help America Vote Act (HAVA), all first-time voters in federal elections in every state must show some form of ID at the polls if they registered by mail. (They do not need to show ID if they registered in person.) States are allowed to augment identification requirements beyond this “HAVA minimum” for all voters, first-time or not.

States with HAVA-minimum requirements typically require voters to announce their name and address at a check-in table when they vote in person. Many of these states also require the voter to sign in. Falsely claiming to be a registered voter is voter impersonation fraud and is a felony in most states.

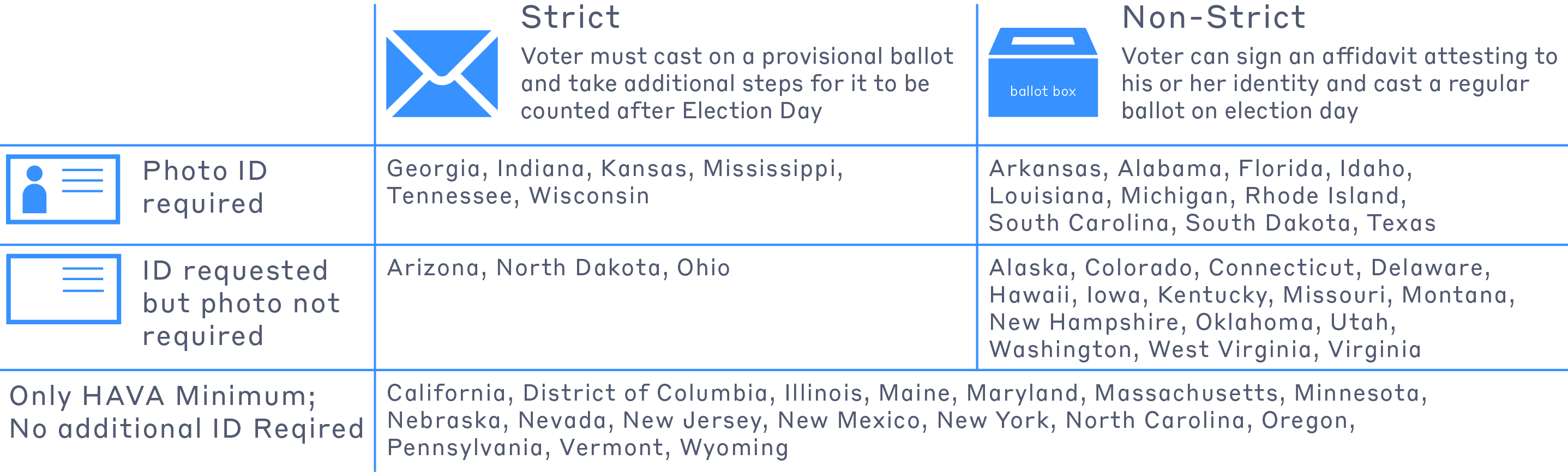

The National Conference of State Legislatures (NCSL) has created a useful two-dimensional classification system to describe the types of voter identification requirements for states that go beyond the HAVA minimum. The first dimension is whether the state requires the voter to show an ID with a photograph. The second dimension is whether a voter without proper ID is required to cast a provisional ballot and then take some additional steps after Election Day to have the ballot counted (“strict” states), or whether such a voter can sign an affidavit attesting to his or her identity and cast a regular ballot on Election Day (“non-strict” states).

The following map summarizes voter ID laws as of the summer of 2020. As a general matter, the strictest ID laws are in the South and Great Lakes states; the least strict laws are in the Northeast and the West Coast.

State voter ID laws are very detailed, so this article only summarizes voter ID policy. If you are interested in the details of voter ID laws in your state, consult your state or local election officials. The U.S. Vote Foundation has a look-up tool with useful state-specific election information.

Voter ID laws in general only apply to those who vote in person. (The exception is first-time voters who registered by mail.) Under HAVA, these voters must include a photocopy of their identification if they vote for the first time by mail.) The identification of voters who cast their ballots by mail, whether a traditional absentee or vote-by-mail ballot, is typically handled by matching the signature on the outer return envelope with the signature election officials have on file.

Legal controversy

Prior to the 2000 election, voter ID laws were not very controversial. Most states had what are now known as HAVA-minimum requirements, although some had non-strict, non-photo ID laws.

Photo ID requirements were given a boost by two efforts that followed the 2000 presidential election controversy. First, ID provisions pertaining to first-time voters were a concession made by Democratic sponsors of HAVA to Republicans to get the law passed in the Senate. Second, in its 2005 report, the Commission on Federal Election Reform (the Carter-Baker Commission) recommended that all states institute photo ID requirements.

The first state to pass a strict voter photo ID requirement was Indiana in 2005. The law was immediately challenged by the Marion County (Indianapolis) Democratic Central Committee as imposing an undue burden on voting rights under the 14th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. Both the federal trial court and the circuit court of appeals rejected these claims. The U.S. Supreme Court granted a writ of certiorari; in Crawford v. Marion County Election Board, the justices ruled that states had a reasonable interest in preventing election fraud and that photo ID laws were not, on their face, unconstitutional. In upholding the Indiana law, however, the court opened up the possibility that the particular facts surrounding other states’ ID laws could be used to strike them down.

The 2008 Crawford decision was seen as a green light both to supporters and opponents of stricter ID laws. To supporters, Crawford signaled that “reasonable” ID requirements, motivated by a desire to prevent voter fraud, would likely be found constitutional. To opponents, the Crawford decision laid out a possible path to future challenges. While the Supreme Court ruled that photo ID laws were not unconstitutional on their face, it did signal that if opponents could show specific harms to voters that outweighed states’ interests in curbing fraud, strict voter ID laws might be struck down.

The number of states that had some type of voter ID requirement rose significantly between the presidential elections of 2004 and 2008 (see Figure 2). The fastest-growing categories of ID laws involved photo identification, although most states with photo ID requirements still fall into the non-strict category.

A second spur to the passage of formal ID laws, especially strict photo ID laws, was the Supreme Court’s decision in Shelby County v. Holder. This 2013 case related to the federal pre-clearance provisions of the Voting Rights Act (VRA). Prior to Shelby County, states “covered” under Section 5 of the VRA (primarily states that seceded during the Civil War) were required to have any election-related voting procedure changes pre-cleared by the Justice Department. To be granted pre-clearance, a state covered by Section 5 would have to show that an ID law did not make minority voters worse off in their “effective exercise of the electoral franchise.” Although Section 5 did not altogether stop the passage of stricter photo ID requirements — Georgia’s strict photo ID law was precleared by the Department of Justice in 2006 — it put a damper on states that might have otherwise attempted to pass them.

With pre-clearance effectively gutted due to the court’s decision that the coverage formula outlined in Section 4 of the VRA was outdated, southern states were emboldened to adopt stricter ID laws. Several states, including North Carolina and Texas, moved quickly to enact photo ID laws that were much stricter than those from the previous decade.

Even more changes to voter identification law and election administration resulted from the 2020 presidential election, in which many Americans opted to vote by mail due to the coronavirus pandemic. The election spurred an expansion of vote by mail eligibility throughout the country, but also led some members of the Republican party and their constituents to doubt the veracity of the election and worry that voter fraud was rampant because of absentee ballots.

As a consequence of this new skepticism about the security of absentee ballots, several Republican-controlled legislatures have increased identification requirements for mail ballots--in many cases adding them when they had previously been nonexistent. Examples of laws passed early in 2021 were those enacted in Georgia (SB 202), Florida (SB 90), and Montana (SB 169). Rather than require a copy of one’s photo ID, per se, these bills require those returning mail ballots supply their driver’s license number or the last four digits of their Social Security number.

Research on voter ID

Voter ID has been the subject of intense scrutiny from the scholarly community. One topic of great interest has been the disparate impact photo ID laws have had on racial minority groups and turnout.

Research associated with litigation in which voter rolls have been matched against driver’s license lists has confirmed this finding in states such as North Carolina, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, Texas, and Wisconsin. (Whether these differences have been sufficient to invalidate the laws has varied across courts.)

Whether the lack of IDs leads to a decrease in turnout is still open to dispute. Some early studies by Ansolabehere and Mycoff et al found no statistical association between strict ID laws and decreased turnout. A more recent study by the GAO has shown a negative correlation between strict photo ID laws and turnout. This finding has been supported by other research (here and here). However, there are methodological challenges to estimating the true causal effects of strict voter identification law, including deficiencies in data quality and sensitivity of results to choices made in statistical estimation (here and here).

While it may seem obvious that voter ID laws serve to depress turnout (even if descriptively and not causally), scholars have made important arguments that the very presence of voter ID laws can have a counter-mobilizing effect that encourages greater turnout among voting populations that are targeted by those laws.

Another important research issue is whether ID laws are implemented consistently as written. Based on studies involving close observation of poll workers, at least two articles (here and here) suggest that inconsistent implementation may be common.

Another aspect of voter ID laws is the effect of these laws on the confidence of voters. Research into this question was partially inspired by the argument of the Supreme Court in Marion County that a rational justification for a state passing a strict ID law is to instill greater confidence in the electoral process. However, the research conducted on this question (see here and here) has not found a consistent correlation between the presence of strict ID laws in a state and an increase in voter confidence (or a decrease in the belief that fraud is rampant). Scholars have also studied factors that lead states to adopt strict ID requirements. Strict ID laws are fairly popular among all elements of the mass public, including Democrats, minority groups, and liberals. Still, Republicans, conservatives, and whites are more likely to approve of these laws. What prompts a state legislature to adopt a strict photo ID law appears to be a confluence of three factors:

- a Republican takeover of the state government after years of Democratic control,

- being a “battleground state” (i.e., a state hotly contested by the political parties), and

- being racially heterogeneous.

While these factors are not present in all states that have adopted strict photo ID laws, they are common to most.