This explainer was last updated April 25, 2023.

Introduction

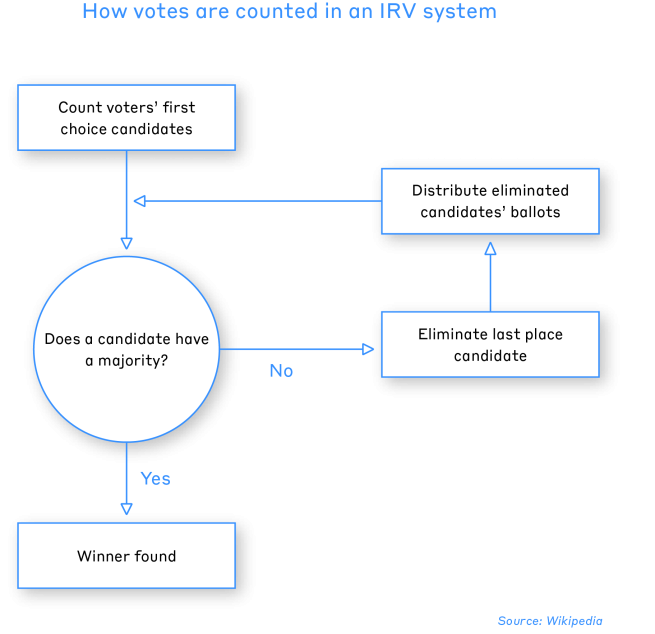

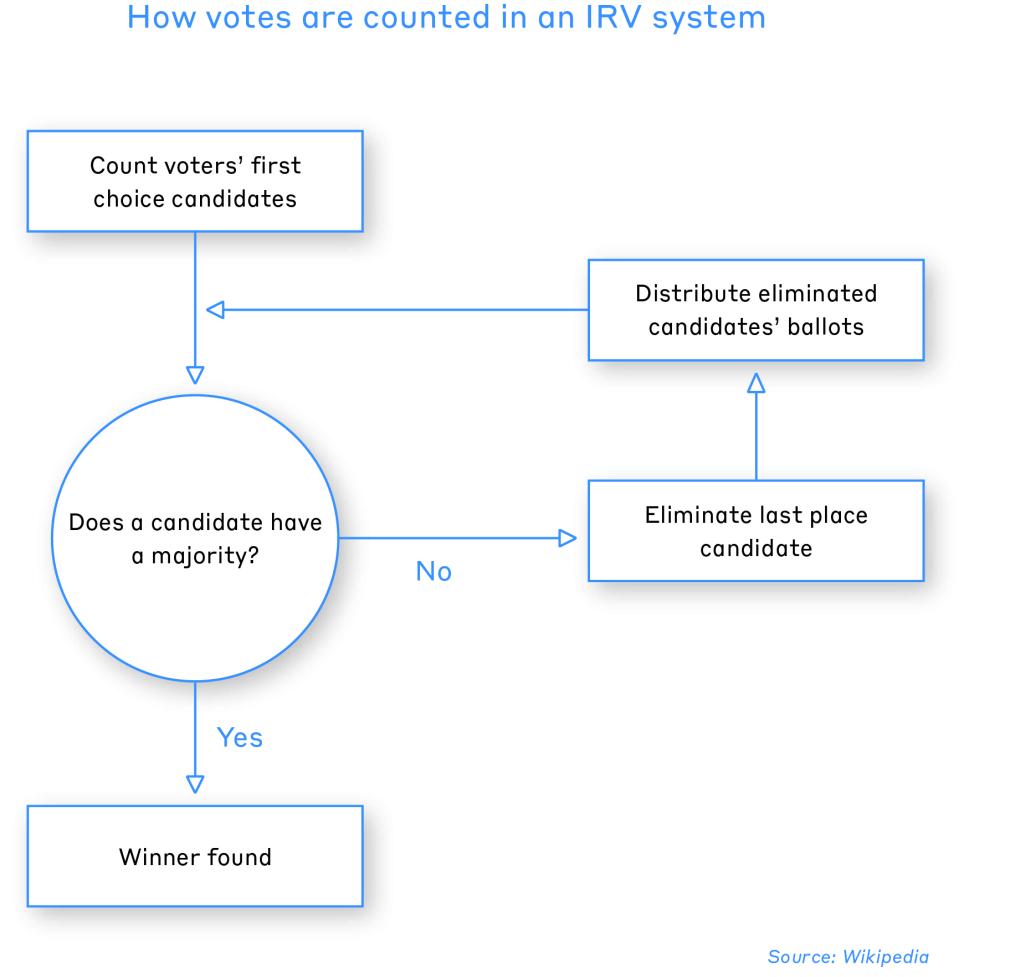

In IRV, ballots are initially counted for the voter’s highest-ranked choice. A candidate wins if they obtain more than 50% of first-choice votes. If no candidate receives more than half of first-choice votes, the candidate with the fewest votes is eliminated. Voters who ranked the defeated candidate as their top choice then have those votes added to their next choice. This process continues until one candidate receives over 50% of the votes.

IRV is used in national elections in several countries around the world, including presidential elections in India and for the Australian House of Representatives. In the United States, IRV is currently used in two states (Alaska and Maine), two counties, and 58 cities. In six states, military and overseas voters cast IRV ballots in federal runoff elections.

History of IRV

Instant runoff voting is a close cousin of the multi-winner election system, Single Transferable Vote (STV), which was adopted in Europe in the 1850s. STV was first used to elect the Danish Rigsdag (the national legislature) in 1956, and was adapted for indirect elections to the Landsting (upper chamber) in 1966. In the 1870s, IRV was implemented at Harvard College by MIT professor and architect William Robert Ware, who adapted the method to the single winner (or instant runoff) form.

Following trial runs in Denmark, the first implementation of an IRV-like system beyond Europe was in the 1893 general election in Queensland, Australia, where all but two candidates were eliminated in the first round. The country would later adopt IRV in its single-winner form in 1908 for its legislative elections. The Republic of Ireland and Malta also implemented multi-winner, ranked-choice election systems for their Parliamentary elections in 1921.

The first use of IRV in the United States was in Ashtabula, Ohio in 1915 to elect its city council members. IRV spread across the state and was soon adopted across the country in cities including Kalamazoo, Michigan; Boulder, Colorado; and Sacramento, California. In 1936, New York City implemented IRV for their school board and city council elections, which inspired 11 other cities around the U.S. to adopt the method. By the 1940s, around two dozen cities were using IRV.

As IRV grew in popularity, so too did its opposition. Politicians who were disadvantaged by IRV (due to an increasing number of their constituents voting for third-party candidates) were so successful in their anti-IRV campaign that by 1962, the method had been repealed in 23 of the 24 cities where it was previously adopted (Cambridge, Massachusetts was the only city that retained an IRV-like system to elect their city council and school board). However, in the decades since its initial proliferation and pushback, IRV slowly regained popularity internationally: in the past 50 years, Northern Ireland (1970), New Zealand (1992), and Scotland (2007) all implemented IRV in either its single or multi-winner variation. More recently, IRV has seen a resurgence in popularity in the United States as well.

Debates Surrounding IRV

Despite being adopted by around 50 U.S. cities in the last decade, the effects of IRV remain widely contested. This section will analyze prominent dimensions of the IRV debate by presenting evidence from proponents, opponents, and electoral scholars.

IRV and Strategic Voting

Since voters in an IRV system have the ability to rank multiple candidates, it is less likely that vote splitting will occur (an outcome where the distribution of votes among several ideologically similar candidates reduces their chances of winning and instead benefits an ideologically dissimilar candidate.) Those in favor of IRV often cite the system’s insulation from this so-called “spoilage” as one of its main benefits; voters know that if their first choice fails to win, their vote automatically gets allocated to their second choice. According to Fair Vote, a nonpartisan nonprofit organization in support of Instant Runoff Voting: “This frees voters from worrying about how others will vote and which candidates are more or less likely to win. Candidates can compete without fear of “splitting the vote” with like-minded individuals.”

However, IRV’s claim to de-incentivize strategic voting may be overstated. An 2022 analysis by Andrew Eggers and Tobias Nowacki found that IRV is not resistant to strategic voting at all, and that voters can and would act strategically under such a system.Both this paper and others (such as Laurent Bouton’s 2013 work) evoke Arrow’s impossibility theorem– there is no election system can entirely eliminate strategic voting without sacrificing other important principles of fairness. Additionally, IRV is a non-monotonic election system, meaning that a winner can become a loser even when they experience increasing support, and a loser can become a winner when they experience decreasing support.

A real-world example of this happening was in the 2009 mayoral election in Burlington, VT, where candidate Bob Kiss ended up winning because some voters ranked him too low (put differently, he would have lost if some voters ranked him higher). This election failed to pass the monotonicity test: ranking a candidate higher should never cause that candidate to lose, and ranking them lower should never cause that candidate to win. In sum, ranking one’s favorite candidate first in IRV is only advantageous if that candidate is very strong or has a very low chance of winning. It is entirely possible that ranking one’s sincere first choice will ultimately force that candidate into a final round with a candidate who is most dissimilar to them (and the latter candidate wins by receiving more displaced second-choice votes).

It is worth noting that the frequency of the monotonicity problem in IRV elections is debated. Some theoretical results suggest that it could be very common, while others who have analyzed data from real elections have not found the problem to be very prolific.

IRV and Increased Representation

There is an extensive body of literature supporting the notion that IRV increases representation for marginalized gender and racial groups. Proponents claim IRV reduces the barrier for entry for minority candidates since they are not as likely to be perceived as spoiled votes. Let’s take women candidates’ performance as an example. Researchers from the nonprofit organization RepresentWomen found that between 2010 and 2019, women candidates won 48% of elected seats across 19 municipalities under IRV. In the 13 U.S. cities that use IRV to elect their mayor, women hold 6 of those seats (46% percent). This is significant when compared to cities with a population of 30,000 or more where women make up only 23% of mayors. As another example, cities in California that conduct IRV elections have seen an increase in the number of women candidates and candidates of color running for office and winning compared to cities that do not use IRV.

While it is true that many jurisdictions with IRV have witnessed a surge in minority representation since its adoption, however, it’s important to note that correlation is not causation. In other words, there may be other factors influencing the increased representation of minority candidates that are completely unrelated to the electoral system. For example, the significant minority representation in the Bay Area could be more prosaically because the region is one of the most racially diverse in the country. Cities experience representative changes over time for a myriad of reasons, and IRV is just one of many potential causal mechanisms. Furthemore, the studies that suggest IRV promotes more diverse representation only analyze these effects at the local level. There are no results that suggest IRV would lead to these outcomes at the state or federal level.

IRV and Partisan (Dis)advantage

IRV has been criticized by prominent leaders on both sides of the political aisle in the US: Republican Senator Tom Cotton referred to the system as “a scam to rig elections,” and Democratic party leaders called IRV “exclusionary” when the system was being debated in Nevada. Despite these claims, there is little evidence to suggest that either Democrats or Republicans are disproportionately advantaged or disadvantaged by IRV. When considering the relationship between political parties and voting systems, it is crucial to recognize that both shape the other. Just as it has yet to be proven that IRV leads to increased political representation of minorities, one cannot make the causal claim that IRV shapes partisan outcomes. Simply put, IRV is just an alternative way to run elections, and claims that the system encourages the tampering of elections are blatantly false.

While the two major parties don’t substantively benefit from IRV, research does support the notion that IRV increases support for third party candidates. One analysis found that third party and independent candidates running for federal office in Maine in 2020 received greater support compared to those running in plurality or runoff systems elsewhere. Furthermore, a 2021 study concluded that ideologically extreme candidates are not viewed as more electable than moderate candidates in both IRV and plurality voting systems, though liberals were more likely to favor moderate candidates over extreme candidates than conservatives. On the other hand, political parties adapt to structural voting changes over time. Take Australia as an example: after more than a century of IRV elections, the country’s politics are largely dominated by two major parties.

IRV and Campaign Rhetoric

Proponents of IRV often highlight the fact that the system encourages more civil campaign rhetoric since candidates are competing for second-choice votes from their adversary’s supporters. A 2021 paper analyzing tweets and newspaper articles related to IRV found that candidates campaigning under an IRV system were more likely to engage with one another positively than those running in plurality elections. Furthermore, survey research found that voters perceive IRV elections as more civil than plurality elections. Myrna Melgar, a member of San Francisco’s Board of Supervisors who was elected in 2020 under IRV, expressed her positive campaigning experience:

“Now that I’m a sitting supervisor, having run [in an RCV election] has helped me quite a bit because I now have all of these alliances with people in my district who were not part of my natural coalition but now have my ear and vice versa. And I think that’s a good thing for governing.”

While there are numerous studies and personal anecdotes to suggest that IRV encourages more civil campaigning (though the majority of these are confined to the local level), this notion remains substantively unproven. There have been many IRV elections featuring harsh campaign rhetoric (for example, Andrew Yang received intense scrutiny when he ran as an Independent candidate in New York City’s mayoral election), and it is unclear how the system affects the campaign messages of advocacy groups. In short, there are instances where IRV has been correlated with increased campaign civility, but there is a shortage of evidence to suggest that this is universally true.

Is IRV Complicated?

Since IRV is unlike how most of the United States has historically conducted elections, there is a widespread apprehension that its implementation would cause confusion amongst voters. Several studies have countered this concern: a 2021 paper found that IRV does not increase the likelihood of voters making mistakes that render a ballot uncountable, and a 2020 survey experiment concluded that ranked-choice ballots resulted in even fewer errors than choose-one ballots. When it comes to voter understanding of IRV elections, survey research finds that an overwhelming majority of voters in many places find the system to be very intuitive. 90% of surveyed voters in the Maine 2018 primary reported that their experience with IRV was “excellent” or “good,” despite most never having used IRV before. 95% of respondents across all ethnic groups who voted in the New York City 2021 primary said that their IRV ballot was “simple to complete.”

However, there is also a body of literature that casts doubt on the ease of IRV. A 2019 survey asking voters in IRV and plurality cities to self-report their understanding of voting instructions found that those in IRV cities found instructions more difficult than those in plurality cities, particularly amongst older voters. A study of IRV voters in the 2020 primary reported the same pattern amongst elderly voters with little to no disparity amongst racial, ethnic, or socioeconomic groups. There have also been numerous instances of difficulties with IRV in election administration under current technology. For example, a school board election in Oakland, CA was overturned because of incorrect settings on their IRV voting machines. Vote tallying errors in New York City and Alaska were ultimately found to have been directly caused by instant runoff voting.

The lack of comprehensive research on this topic makes coming to a concrete conclusion about the ease of IRV difficult. While survey research largely concludes IRV to be well understood by voters, there is still a question of how well voters truly understand the intricate and far-reaching consequences of IRV. One may feel they grasp how a system works but be unable to wholly recognize or explain its larger implications. Furthermore, there is no evidence to suggest large-scale disenfranchisement is occurring as a result of IRV, though it may be beneficial for certain jurisdictions to invest more in voter education.

Conclusions

Despite having been utilized in democratic elections for over a century, much remains to be explored about the use of instant runoff voting in practice, particularly in the United States. Certain research highlights the benefits of IRV by lauding the system’s ability to reduce the spoiler effect, increase electoral representation for racial and gender minorities, and promote more civil campaign strategies. While there is some evidence to support these claims, most of this research is inconclusive. Instant runoff voting is a legitimate way to select representatives, and it very well may be more democratic and inclusive than other methods. However, this system is complicated, and much more research needs to be done before definitive claims are made about the method’s efficacy. It is clear that the field of election science would greatly benefit from more research on IRV in practice, which will ultimately contribute to the ever-important project of protecting American democracy.

Suggested Resources

Monotonicity - Center for Election Science

Favorite Betrayal in Plurality and Instant Runoff Voting - Center for Election Science (video)

Ranked Choice Voting - FairVote

Ranked Choice Voting - representUs

Maine ranked-choice voting as a case of electoral-system change. Santucci, 2018.

Ranked-Choice Voting Is Not the Solution - Democracy Journal