Although voter registration has been the subject of recent controversy, our democracy did not always require people to register to vote. Today, all states except for North Dakota have some form of voter registration, and some are looking at reform that makes registering to vote easier and more accessible.

Though most laws and regulations relating to elections are handled by the states, a few federal laws guide voter registration nationwide. The most important of these are the 1965 Voting Rights Act (VRA) and the 1993 National Voter Registration Act (NVRA). The VRA prohibits racial discrimination in voter registration; the NVRA requires that states make voter registration widely available and limits what they can do to remove voters from the rolls. In recent years, states have implemented new ways to register, including online voter registration and automatic voter registration.

This explainer was last updated on January 9, 2024.

Background

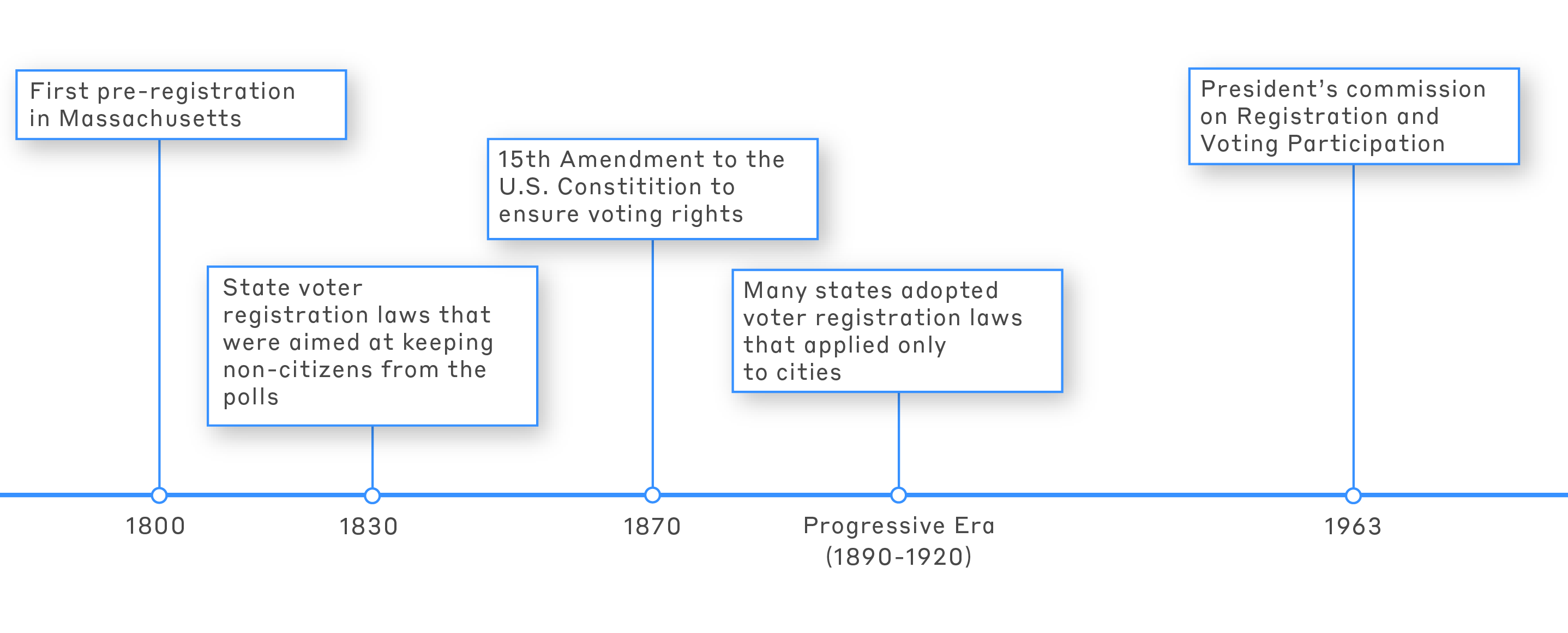

Pre-registration hasn’t always been a requirement to vote. In the earliest years of the republic, it was assumed that local officials personally knew the small number of residents in their towns who met the property qualifications to vote. Massachusetts instituted the first pre-registration requirement in 1800. The earliest registration processes were mostly used to enforce the requirement that qualified voters must pay their taxes. Anti-immigration agitation in the 1830s saw another wave of state voter registration laws that were aimed at keeping non-citizens from the polls. (Until then, several states granted non-citizens the right to vote.) Still, throughout most of the 19th century, pre-registration was not a requirement to vote in all states.

Voter registration that resembles modern practices began in the late 1800s when states expanded their registration requirements, paying particular attention to controlling the voting of city dwellers, immigrants, and African Americans. During the so-called Progressive Era (1890–1920), many states adopted voter registration laws that applied only to cities. Among the reasons for this specificity was the desire of rural-dominated state legislatures to blunt the political power of rapidly growing urban areas, which were growing largely through the influx of new immigrants. In addition, stories of political corruption and vote fraud, such as “repeat voting,” tended to arise most often in urban settings.

Despite the ratification of the 15th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution in 1870 stating the “right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged... on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude,” the Union and its states continued to pass many laws that denied Black Americans their newly won constitutional rights. As chronicled by C. Vann Woodward’s classic book, The Strange Career of Jim Crow,

the official disenfranchisement of Black Americans heightened in the South just as Black politicians began to gain power. In addition to imposing extraordinary voting requirements such as literacy tests that disadvantaged Black citizens, Southern voter registration, in general, was becoming increasingly burdened by registration regulations.

State voter registration laws that sprang up at the turn of the twentieth century applied to voters of all races and deterred the participation of all but the most persistent citizens. For instance, many states required voters to register annually, and/or removed voters from the rolls if they failed to vote in an election. Registration closing dates—the date on which the voter registration rolls would be closed before an upcoming election—were often months ahead of elections. Even as late as 1972, five states cut off registration more than a month before an election.

The civil rights movement that succeeded in the passage of the Voting Rights Act also spawned related movements that called for lowering voter registration barriers for reasons other than race. The President's Commission on Registration and Voting Participation appointed by President Kennedy in early 1963 recommended a series of reforms to ease voter registration, most of which were eventually adopted. Among these were reducing the gap between registration closing dates and elections, reducing residency requirements, and increasing opportunities to vote absentee.

NVRA

The National Voter Registration Act (also known simply as the “NVRA” or the “Motor Voter Act”) of 1993 represented the culmination of a quarter-century of efforts to relax the strict voter registration requirements that had grown over the previous century. Before its enactment, efforts had been made to pass federal laws instituting a national “postcard” registration form, as well as to encourage states to adopt “motor voter” laws—that is, laws allowing citizens to register when they got their driver’s licenses.

The first attempt to pass the NVRA failed in 1992 when Congress passed the law but President George H.W. Bush vetoed it. One year later, Congress passed a similar measure, which was signed into law in 1993 by President Bill Clinton. The NVRA contained the following major provisions:

- States were required to allow voter registration by mail.

- States were required to offer voters the opportunity to register to vote simultaneously when applying for a driver’s license and were also required to offer registration at public assistance agencies.

- States were not allowed to remove voters from the rolls solely for non-voting. Voters were allowed to be removed only if they requested it or if they died, moved out of jurisdiction, or were removed because of a felony conviction or mental incapacity.

Although the NVRA prohibited the removal of voters from the rolls simply for non-voting, it did allow states to use non-voting as a trigger to inquire whether a non-voter had moved from the jurisdiction without notifying local election officials. In particular, a state can remove someone from the rolls if it sends a notice to a non-voter and the non-voter fails to respond (or vote) within the next two federal elections.

In 2018, the U.S. Supreme Court considered the issue of how aggressively states can initiate the removal process when people fail to vote. In Husted v. A. Philip Randolph Institute, the court ruled that Ohio’s practice of initiating the removal process, by sending a mailed notice to non-voters after their first missed election, was allowed under the NVRA.

The NVRA exempted states that either did not have a voter registration requirement or allowed registration on Election Day at the polls at the time the NVRA passed. Later, the exemption was extended to two states that passed Election Day registration soon after the passage of the NVRA. As a result, Idaho, Minnesota, New Hampshire, North Dakota, Wisconsin, and Wyoming are the only six states exempt from the NVRA.

How many are registered?

The Election Assistance Commission’s 2022 report on the implementation of the NVRA stated that there were over 203 million active registered voters in the 50 states plus the District of Columbia. With an estimated voting-eligible population of 226.4 million, this suggests that about 90% of eligible voters are registered and on the voting rolls.

However, these registration statistics are undoubtedly an overestimate due to the persistence of deadwood on the rolls. Precisely how much deadwood persists on voter rolls is unknown and subject to intense research and public debate. In his paper “Too Large, Too Small, or Just Right?”, Charles Stewart finds that much of the deadwood on the rolls results from a failure to remove voters once they move rather than accidentally retaining dead voters on the rolls.

Another way to estimate the amount of deadwood is to examine the number of inactive voters in states that distinguish between active and inactive voters. (In general, states that use the “inactive” voter category will move a registered voter to inactive status when they have reason to believe the voter has moved or died but have yet to receive definitive confirmation.) In 2022, among the states that use the inactive status, 11.1% of registrants were inactive, ranging from 6.1% in Virginia to 24.6% in D.C. Taking the inactive percentage as an estimate of the amount of deadwood on the voter rolls, this would suggest that the actual voter registration rate nationwide is closer to 80% of the eligible electorate.

An alternative approach to estimating the number of people registered in each state is to rely on answers to survey questions that ask whether respondents are registered to vote. This approach is used by the Elections Performance Index, justified in part by analysis performed by Barry C. Burden in the book The Measure of American Elections. Burden notes that survey-based measures of registration rates are correlated with the rates reported by states using official rates, but that they are generally less extreme than the state-reported rates.

The following two maps illustrate reported voter registration rates in 2022 using two methods. The first map shows registration rates based on the officially reported number of registered voters in each state. The second map relies on responses to the 2022 Voting and Registration Supplement of the Current Population Survey, conducted by the U.S. Census.

A map of the US showing voter registration rates based on the officially reported number of registered voters in each state. A lighter color indicates a lower registration rate, and a darker color indicates a higher registration rate.

A map of the US showing voter registration rates based on responses to the 2022 Voting and Registration Supplement of the Current Population Survey, conducted by the U.S. Census. A lighter color indicates a lower registration rate, and a darker color indicates a higher registration rate.

The initial thing that becomes apparent in the first map is that there are two states with more registered voters than the estimated citizen voting-age population (Alaska and D.C.). This is clear evidence of significant deadwood on the rolls of these states, but it does not mean that significant deadwood doesn’t exist in states with official registration rates less than 100%.

By design, no state in the second map has registration rates exceeding 100%. According to these data, Oregon had the highest registration rate (as a function of voting age population) at almost 83 percent, with D.C. tailing behind a close second with 82.4 percent. The state with the lowest registration rate is North Carolina, coming in at 60.8 percent.

The presence of more voters on the rolls than the citizen voting age population (CVAP) has been used as evidence that voting lists are ripe for fraud. This is unlikely since the “excess” in registrations is primarily due to people remaining on the rolls despite no longer being residents of the state or having died. Fraud related to voting for deceased residents is very rare, although when it happens, it attracts press attention. In any event, if we use official statistics to gauge the number of “actual” registrants in a state, the number of people in active status is a better statistic than the total that includes inactive voters.

New developments

States have increasingly been adopting new approaches to voter registration. This has been spawned by a mix of citizen activism aimed at mobilizing new voters, the concern of public officials with low turnout rates, and the desire to take advantage of computer technologies to decrease the costs of registering voters while at the same time increasing the accuracy of voter lists.

The first new development is a resurgence of interest in Election Day registration, sometimes called same-day registration. Minnesota was the first state to implement Election Day registration in 1974, but for the vast majority of states, this registration policy’s popularity ramped up after 2000. The National Conference of State Legislatures reports that as of October 2023, 20 states and D.C. have implemented same-day voter registration. Of these 20, 18 allow their citizens to register and vote simultaneously. The other two, Montana and North Carolina, allow citizens to register and vote only during the early voting period; the rest allow registration and voting on Election Day itself. (Montana had previously allowed registration on Election Day, but that was abolished in the 2021 state legislative session.)

The second new development is online voter registration (OVR). As the name implies, online voter registration allows citizens to register to vote online. In general, a voter fills out a registration form electronically, which is then verified by voting officials at the state level. Usually, voters using OVR must already have a driver’s license or another form of state identification. OVR was first adopted by Arizona in 2002, and since has been adopted by 42 states and D.C. Arizona’s experience with OVR—which lowered costs and decreased data errors—has spurred a steady increase in state adoptions since then.

The final notable recent development in voter registration is automatic (or automated) voter registration (AVR). AVR goes one step further than the traditional “motor voter” system in which citizens are offered the opportunity to register when they get a driver’s license. Instead of this more traditional “opt-in” approach, AVR is an “opt-out” system, wherein holders of driver’s licenses are automatically registered to vote unless they explicitly ask to be taken off the voter list. AVR was first enacted by Oregon in 2016. Since then, another 24 states have adopted it plus D.C.

Though studies of AVR and voter turnout are still preliminary, there are promising findings showing that AVR does increase rates of voter registration significantly across the board. A Brennan Center analysis from 2019 found that Georgia, in particular, nearly doubled its rate of voter registrations after the implementation of the policy. Indeed, the analysis found that all states that implemented AVR saw a rise in registration rates.

Suggested Readings

Brennan Center for Justice | Automatic Voter Registration, a Summary

Burden, Barry C. 2014. "Registration and Voting, A View from the Top." In The Measure of American Elections, eds. Barry C. Burden and Charles Stewart III. New York: Cambridge University Press, 40–60.

Census | Voting and Registration in the Election of November 2020

Center for American Progress | Who votes with automatic voter registration?

Harris, Joseph. 1929. Registration of Voters in the United States. Brookings Institution.

Key, V.O Jr. 1949. Southern Politics in State and Nation. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press.

Keyssar, Alexander. 2000. The Right to Vote: The Contested History of Democracy in the United States. New York: Basic Books.

MIT Election Data and Science Lab. Voter List Maintenance.

MIT Election Data and Science Lab. Automatic Voter Registration.

National Conference of State Legislatures | Automatic Voter Registration

National Conference of State Legislatures | Same Day Voter Registration

National Conference of State Legislatures | Online Voter Registration

U.S. Election Assistance Commission | National Voter Registration Act Studies

Woodward, C. Vann. 1955. The Strange Career of Jim Crow. Oxford University Press.