One tool election administrators can turn to, as many did after the 2020 election and in many less high-profile, close contests, is the post-election audit (PEA), sometimes more accurately termed the post election tabulation audit. Post-election audits are critical for election security and voter confidence in contests large and small, national and local. Consequently, most states require such audits, though the techniques mandated and used vary.

Election audits “are intended to accomplish two things,” as a 2018 report from the MIT Election Data + Science Lab and the Caltech Voting Technology Project put it:

- The first is to ensure that the election was properly conducted, that election technologies performed as expected, and that the correct winners were declared.

- The second is “to convince the public of the first thing.”

This explainer will outline what post-election audits are, what they are not, how they function, and will detail a few of the most common auditing processes found in the United States.

This explainer was last updated September 4, 2024.

What are audits?

Post-election audits (PEAs) are an essential tool for election administrators to determine systems worked as they were expected to. While there are several different methods by which these audits can be conducted, they generally require paper ballot markings to be compared to tabulated vote totals. The auditing process aims to verify that the ballots were tallied accurately. An inconclusive audit could lead to a partial recount or even a full manual tally of ballots. Generalizing this to the EAC’s more robust definition, a post-election audit is a process through which election administrators validate the tabulated outcome of an election by verifying a sample of ballots, ideally using statistically robust methods specified in advance.

Audits are different from recounts. Recounts are designed to verify the exact vote totals of candidates in a particular contest; moreover, they are usually ordered ad hoc on the basis of election results (say, if a contest was decided by a narrow 0.5% margin). Routine post-election audits, on the other hand, are focused only on determining that the declared victor actually won, not the winning margin.. They are usually announced and described in statute or via administrative order prior to the election. Audits are also more comprehensive, and aim to validate numerous aspects of the election process—not just the results at the end. In fact, the US Election Assistance Commission identifies eight different auditing activities designed to assess different elements of the election process: access audits, ballot design audits, ballot reconciliation audits, compliance or procedural audits, eligibility audits, legal auditis, logic and accuracy testing, and post-election tabulation audits. This explainer will focus on post-election tabulation audits.

Institutionalizing audits

The post-election recounts in Florida’s 2000 presidential contest revealed key weaknesses and vulnerabilities in America’s decentralized, often underfunded elections infrastructure. In response, Congress passed the 2002 Help America Vote Act (HAVA). HAVA funded the new US Election Assistance Commission (EAC), which was enabled to provide grants to states. With these resources, election administrators could purchase new electronic voting machines and phase out less reliable election devices, such as punch-card and lever systems.

HAVA also provided for the promulgation of federal Voluntary Voting System Guidelines (VVSG), which set the standards for voting technology nationwide. The 2007 VVSG required that new voting systems be software independent—a qualification that is true when “an undetected change or error in its software can not cause an undetectable change or error in an election outcome.” This criteria generally demands voter-verifiable paper audit trails (VVPAT) for voting machines. Software-dependent systems, in contrast, bear the risk of producing undetectable tabulation errors that audits cannot identify or remedy, making them especially vulnerable to interference and manipulation. By barring dependent systems, post-election audits can compare electronic and manual tabulation results to confirm election outcomes. This was an important development for election security and transparency.

Traditional audits

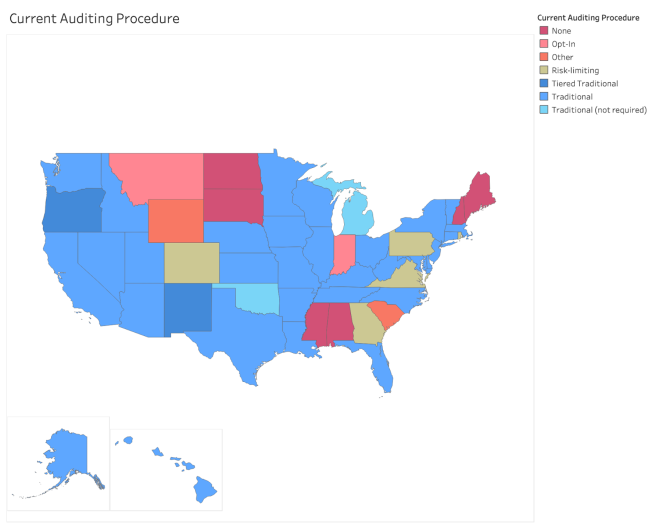

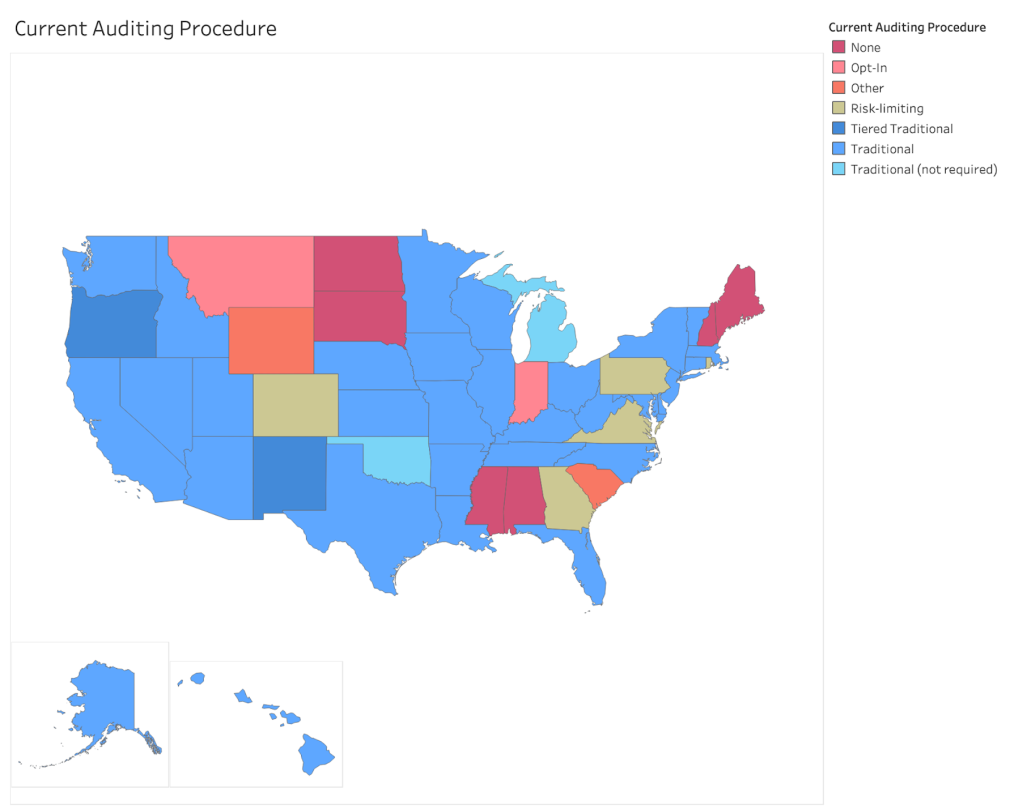

While more than three quarters of states now require post-election tabulation audits, audit types and methods vary significantly. Thirty-four states require traditional audits, while five require risk-limiting audits (RLAs)—a more recent auditing approach that is gaining popularity. Several other states allow jurisdictions or election administrators to opt into post-election audits, and in six states, statutory and administrative policies do not provide for post-election audits at all.

In a traditional audit, election administrators will typically compare the results tabulated by a set proportion of voting machines with the paper record to determine whether there is a discrepancy significant enough to affect the election outcome. If a notable discrepancy is detected, states have different processes in place that outline how their administrators should proceed. Massachusetts, for example, requires three percent of all precincts to be audited after a presidential election; if the first audit raises doubts about the accuracy of the count, the secretary of state can order additional audits. By contrast, in Kentucky, precincts with votes totalling to 3–5 percent of those cast are audited, and discrepancies lead to a re-canvass to correct errors.

Traditional audits generally require the same proportion of machines, precincts, or ballots to be audited regardless of how narrow an election is. Tiered traditional audits, such as those used in New Mexico and Oregon, deviate from this norm. These two states will audit more ballots in close elections than in landslide contests, tying the proportion of precincts to be tested to different tiers of election outcomes. This balances the interest in election accuracy with the resource limitations election administrators face, as decisive margins are less likely to be swung by the kinds of discrepancies audits pinpoint than narrow ones. The map below illustrates what type of audit each state deploys.

Pictured is a map of the United States, with states shaded to indicate what auditing procedure is currently in use. Most states use some form of traditional audits. Five states use risk-limiting audits. Six states do not require any post-election audits. Pennsylvania requires a traditional audit via statute but recently required a risk-limiting audit via administrative order, and Georgia recently adopted a RLA, so both are counted as RLA states. Data is sourced from the National Conference of State Legislatures, Verified Voting, and statutes.

Pictured is a map of the United States, with states shaded to indicate what auditing procedure is currently in use. Most states use some form of traditional audits. Five states use risk-limiting audits. Six states do not require any post-election audits. Pennsylvania requires a traditional audit via statute but recently required a risk-limiting audit via administrative order, and Georgia recently adopted a RLA, so both are counted as RLA states. Data is sourced from the National Conference of State Legislatures, Verified Voting, and statutes.

Risk-limiting audits

Risk-limiting audits (RLAs) are a new frontier in post-election auditing techniques. Rather than auditing a fixed proportion of precinct results or ballots, as with traditional audits, they are designed to “provide statistical assurance that election outcomes are correct” based on a pre-specified risk limit. The risk limit is the maximum probability that the audit will fail to lead to a manual tally when the observed outcome is incorrect. In other words, if the observed winner actually lost an election, a risk-limiting audit with a 10% risk limit has at least a 90% chance of ordering a hand tally and identifying the error. The primary benefit of RLAs is that they offer policymakers and election administrators with a method for specifying the extent of confidence an audit provides.

The basic mechanism of an RLA is rooted in statistical guarantees derived from the risk limit and observed margin of victory. As more ballots are audited, as with traditional PEAs, discrepancies are noted. In an RLA, though, those discrepancies will push the audit either toward a full manual tally—by requiring more and more ballots to be counted—or toward certification with fewer ballots tallied. The scale of the audit is determined by the method and the reported election margin; as the margin of victory narrows, the number of ballots expected to be audited rapidly increases.

There are three main types of RLAs: ballot-comparison, ballot-polling, and batch-comparison audits:

- In a ballot-comparison RLA, a random selection of ballots are examined manually and individually. Auditors’ interpretations of voters’ markings are compared to computer interpretations of the same ballot. While this is theoretically the most efficient method, as it typically requires the fewest number of ballots to verify the observed outcome, it is not the most practical due to the strain it places on tabulation systems.

- Ballot-polling audits are similar to ballot-comparison audits, except that they tally the results of a group of ballots for each candidate instead of looking at each ballot individually. The vote totals for each candidate from the hand and machine counts are then compared. This method is preferable for some tabulation machines, though it is generally less efficient than the ballot-comparison method and usually requires more ballots to be inspected. It is preferable when individual ballot data (like cast vote records) are unavailable.

- The batch-comparison audit is the least efficient RLA method, though it also is the most similar to a traditional audit. Here, the machine and hand tallies in randomly-selected batches of ballots are compared to determine whether significant discrepancies exist.

Technical advances and differences in RLAs

Statisticians, computer and political scientists, and election administrators have contributed to innovations in risk-limiting audit implementation. New methods have been developed to promote more efficient RLAs, which can save election administrators’ time and money or validate election results more quickly. This explainer will briefly sketch a few cutting-edge techniques.

The simplest technique, BRAVO, was described and proven to be a risk-limiting audit by Mark Lindeman, Philip B. Stark, and Vincent S. Yates in 2011. Auditors using this ballot-polling method randomly select and examine a ballot, noting which candidate a valid vote was cast for before selecting another ballot. This process is continued until the evidence in favor of one candidate winning is sufficiently strong (the threshold here is determined by the risk limit)—thus concluding the audit—or a hand count is ordered. Often, it is less logistically costly (though more inefficient) for jurisdictions utilizing BRAVO audits to sample multiple ballots at once. MINERVA audits use a different statistical model to present a more efficient ballot polling alternative to BRAVO. ALPHA, developed by Stark in 2023, generalizes BRAVO to more circumstances and improves its efficiency by learning from previous ballot results and relying on the same logic as betting martingales. Stark, Lindeman, Kellie Ottoboni, and Neal McBurnett’s SUITE audit improves on other RLA models in a different way: by using stratified sampling methods, it allows jurisdictions that can complete ballot-comparison audits to do so before combining those results with more typical (and inefficient) ballot-polling audits. In states like Colorado, where some counties can conduct ballot-comparison audits, while others can only perform ballot-polling ones, this enables a statewide audit to proceed more efficiently than if only ballot-polling techniques were applied.

RLA Usage

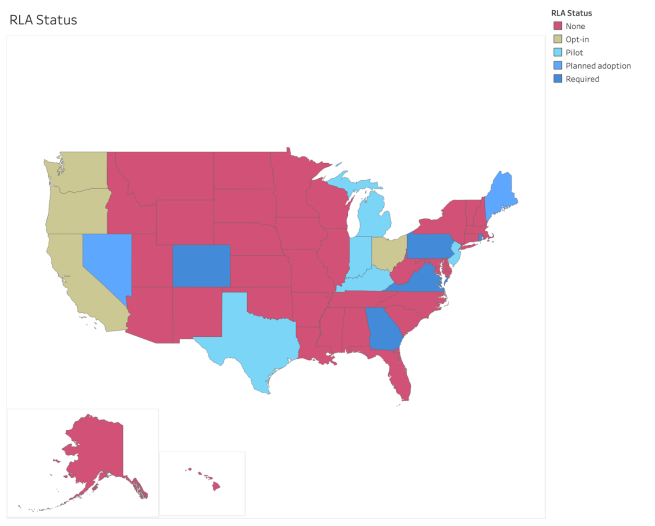

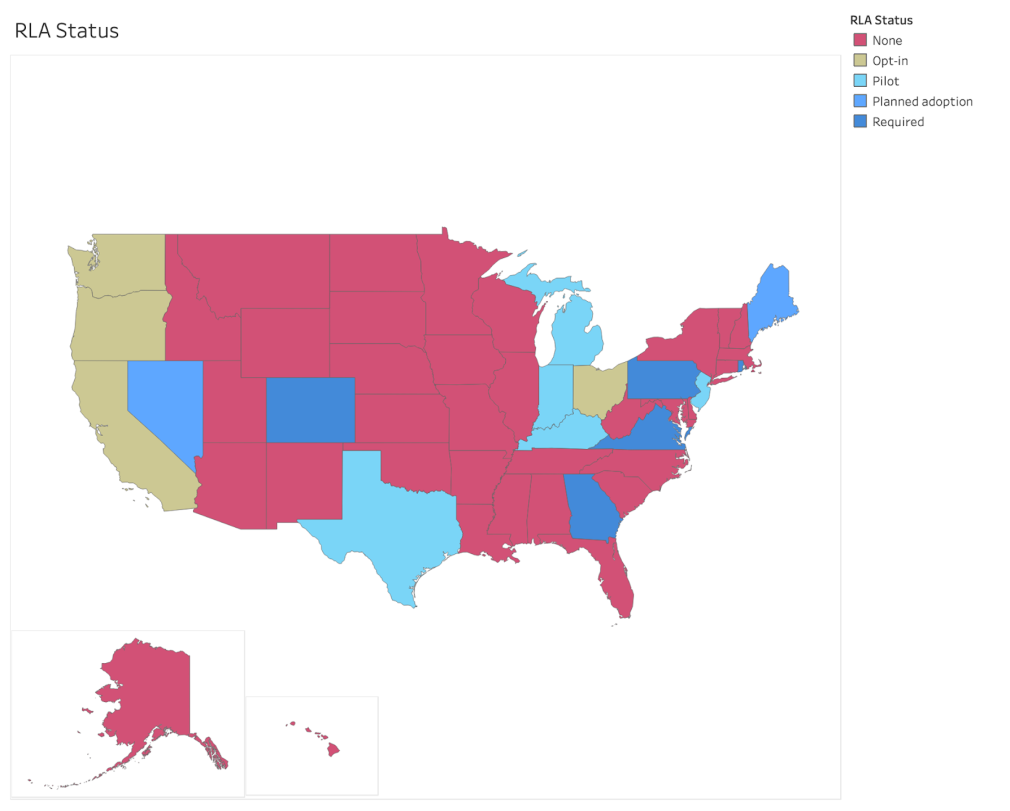

Jurisdictions in many states have been increasingly piloting and implementing risk-limiting audits. In 2009, Colorado was the first state to require an RLA pilot in statute, and the first audit took place in Arapahoe County in 2013. This was followed eight years later by a statewide RLA. In the years since, four more states have adopted RLAs (with two more planning to implement them soon), five are piloting them, and four allow state or local elections officials to opt in. The map below displays the status of RLAs across the nation.

Displayed is a map of the United States, with shadings indicating the status of risk-limiting audits in each state. The vast majority of states do not use RLAs at all. Five states currently do, with two more planning statewide implementation in upcoming election cycles. Four states allow jurisdictions to opt-in and pursue RLAs, while five states are conducting RLA pilots. Pennsylvania requires a traditional audit via statute but recently required a risk-limiting audit via administrative order, and Georgia recently adopted a RLA, so both are counted as RLA states. Data is sourced from the National Conference of State Legislatures, Verified Voting, and statutes.

Displayed is a map of the United States, with shadings indicating the status of risk-limiting audits in each state. The vast majority of states do not use RLAs at all. Five states currently do, with two more planning statewide implementation in upcoming election cycles. Four states allow jurisdictions to opt-in and pursue RLAs, while five states are conducting RLA pilots. Pennsylvania requires a traditional audit via statute but recently required a risk-limiting audit via administrative order, and Georgia recently adopted a RLA, so both are counted as RLA states. Data is sourced from the National Conference of State Legislatures, Verified Voting, and statutes.

Implementing RLAs comes with certain challenges and requirements. Firstly, it is essential that the jurisdiction’s voting systems be software independent, and typically, that requires a paper ballot trail for auditors to use. The types of voting machines used can dictate which RLA methods are possible and preferred. Third, software for managing and executing the audits are a significant aid for election administrators and also public accessibility. For transparency, open-source programs are preferred. And finally, election administrators must ensure that the audit is transparent and publicly accessible. This should apply to each step of the audit: Election officials should document their actions, permit public viewing when ballots are being re-tabulated, and consider public input during randomization processes (e.g. asking observers to roll die in order to produce the seed necessary for a pseudorandom number generator).

Auditing practices and implementation

Determining whether to use a traditional, risk-limiting, or other audit type is only the first step in implementing a post-election audit. State and local election officials must also determine which jurisdictions and contests are audited, what the risk limit is or what differentiates tiers (if applicable), what auditing methods are feasible given the voting equipment used, and how resources and personnel are to be allocated. States should also specify when an audit will occur and how long it can take. This is necessary because states must also meet certification deadlines, making time a crucial constraint. In order to ensure voter confidence, it is critical to ensure that audits are transparent and publicly accessible. Election administrators must determine how to achieve this without compromising ballot secrecy. All of these open policy questions can be resolved via statute or administrative guidelines prior to the auditing process.

In addition to choosing what voting technology to use and what audit method is appropriate, policymakers must decide who has a role in post-election audits. In most states, either statewide or county election officials oversee the audit. Some require interfacing between the two levels of administration, and regulations and guidance typically come from the state election officials. Sometimes, as in New Mexico, an independent auditor works with local officials to oversee the process, while in Connecticut, the secretary of state’s office works in consultation with the University of Connecticut.

State policies on election certification when audits reveal discrepancies diverge substantially. They are also often vague and leave significant discretion to the secretary of state and local officials. Many states’ statutes are silent, and others only require a report to be filed (with or without an investigation). Some jurisdictions mandate a recanvass or a more expansive audit. Discrepancies by themselves do not signify that an election has been compromised—it is not uncommon to find rare overvotes or undervotes—but significant or systematic discrepancies can call an election outcome into question. Some states prescribe the protocols for those rare instances in advance. Others do not.

Conclusion

Post-election audits are critical to election administration and public confidence in election outcomes. Though state policies vary in regards to timing, types, personnel, methods, observations and transparency, technology, and more, states that implement PEAs offer voters validation of the voting technology used and the results of the election. In a political moment when election integrity is especially salient, these audits are all the more essential for preserving voter confidence.

Suggested readings

Fitzgerald, Matthew. "Risk-Limiting Audits in Colorado Elections: A Brief Overview." The Bridge. (September 15, 2020)

Hale, Kathleen and Mitchell Brown. “Administrative Innovations in Counting Ballots: How Election Results Are Verified.” How We Vote: Innovation in American Elections, Georgetown University Press, 2020, pp. 144–61.

Howard, Elizabeth, et al. Risk-Limiting Audits in Arizona. R Street Institute, 2021.

Jaffe, Jacob, Joseph R. Loffredo, Samuel Baltz, Alejandro Flores, and Charles Stewart III. "Trust in the Count: Improving Voter Confidence with Post-election Audits." Public Opinion Quarterly, Volume 88, Issue SI, 2024, Pages 585–607. (July 11, 2024).

Lindeman, Mark and Philip B. Stark. "A Gentle Introduction to Risk-Limiting Audits." IEEE Security & Privacy, 10 (5): 42-49. (Sept.-Oct. 2012)

MIT Election Data + Science Lab | Election Auditing: Key Issues and Perspectives

MIT Election Data + Science Lab | Election Audit Summit: Papers, proceedings, and suggested resources. (December 7-8, 2018)

National Conference of State Legislatures | Post-Election Audits

National Conference of State Legislatures | Risk-Limiting Audits

Stark, Philip B. "ALPHA: Audit that Learns from Previously Hand-Audited Ballots.” The Annals of Applied Statistics, 17(1): 641-679. (March 2023)

U.S. Election Assistance Commission. "Election Audits Across the United States." (October 6, 2021).

U.S. Election Assistance Commission. “State of Colorado Risk-Limiting Audit – Final Report.” (undated)