The movement to vote by mail reached new levels with the 2020 elections and the COVID-19 pandemic, and although it subsequently declined by more than 10 points in 2022, 32 percent of voters chose to cast their ballots this way in that election.

This explainer was last updated on February 28, 2024.

Introduction

Absentee voting and balloting by mail have generally been viewed as synonymous in the United States because historically, absentee ballots were distributed by mail to voters temporarily away from their homes, and typically no one else was allowed to use this mode of voting. For this reason, both topics are considered together in this explainer. The figure below shows the percentage of voters who cast their ballots since 1996 by each of the three major modes of voting—in person on Election Day, in person before Election Day, and by mail/absentee. The statistics are based on self-reports by respondents to the Voting and Registration Supplement of the Current Population Survey (CPS). (The data for 2020 are based on responses to the Survey of the Performance of American Elections.)

A line graph showing the trends of method of voting from 1996 to 2022. The x-axis is the year and the y-axis is the percentage of the electorate. Blue corresponds to vote by mail, orange corresponds to voting in-person before Election Day, and yellow corresponds to voting in-person on Election Day.

The rise in voting by mail (VBM) raises several important academic and policy issues. Do generous vote-by-mail policies increase turnout? Does an increased rate of voting by mail decrease civic engagement, or decrease the impact of an “October surprise,” that is, an event at the end of a political campaign intended to affect the outcome? How does the process of counting votes cast by mail impact when we know the winners of an election?

History and expansion

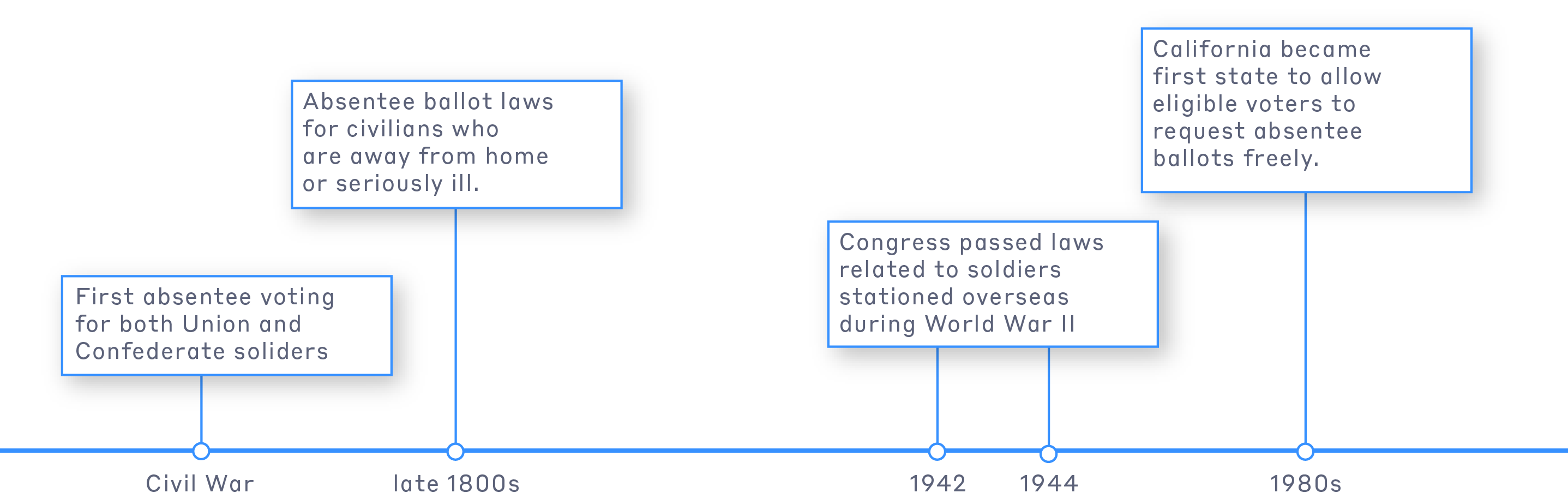

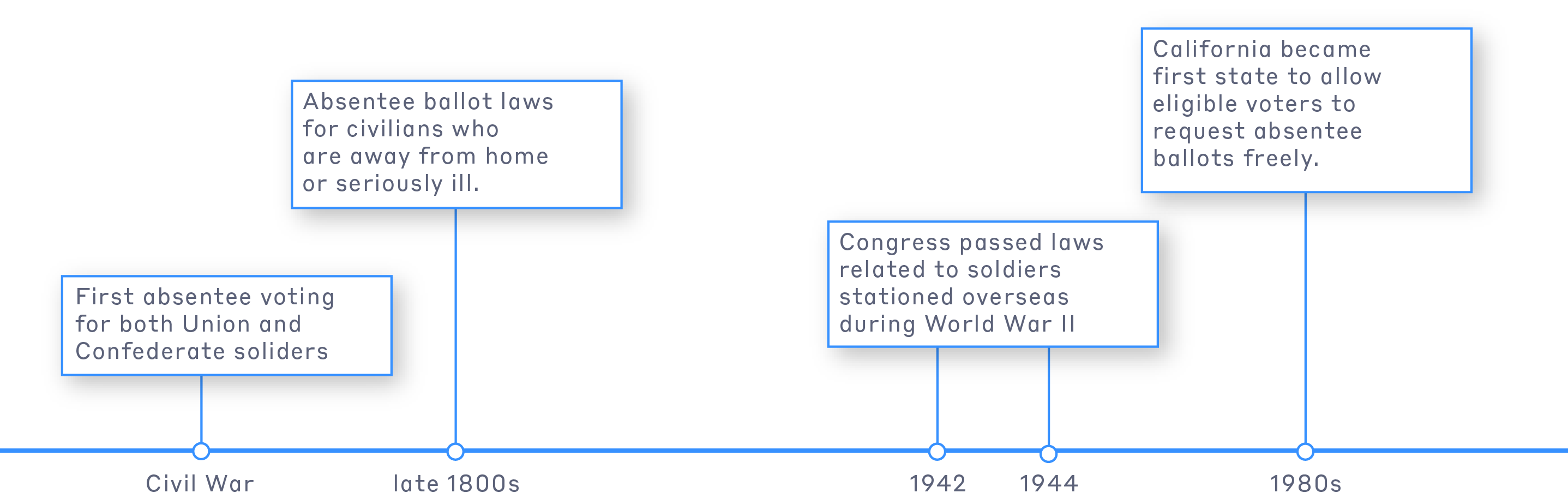

The idea that ballots could be cast anywhere other than a physical precinct close to a voter’s home hasn’t always been embraced in the United States (and still isn’t in many other countries). What we in the U.S. now call absentee voting first arose during the Civil War, when Union and Confederate soldiers were allowed to cast ballots from their battlefield units and have them be counted back home.

The issue of absentee voting next became a major issue during World War II, when Congress passed laws in 1942 and 1944 related to soldiers stationed overseas. Both laws became embroiled in controversies over states’ rights and the voting rights of African Americans in southern states, so their effectiveness was muted. Subsequent laws, particularly the Uniformed and Overseas Citizens Absentee Voting Act (UOCAVA) and the Military and Overseas Voter Empowerment (MOVE) Act, have been more effective in encouraging voting by active service members through absentee voting.

States began passing absentee ballot laws for civilians in the late 1800s. The first laws were intended to accommodate voters who were away from home or seriously ill on Election Day. The number of absentee ballots distributed was relatively small, and the administrative apparatus was not designed to distribute a significant number.

In the 1980s, California became the first state to allow eligible voters to request absentee ballots for any reason at all, including their convenience. By 2023, 28 states and the District of Columbia adopted no-excuse absentee laws. The figure below classifies states according to their absentee/mail ballot regimes. According to data in the 2022 Election Administration and Voting Survey (EAVS), an average of 23.3% of voters in no-excuse states cast their ballots by mail, compared to an average of 5.4% in states that still required an excuse.

A map of the United States showing the distribution of absentee ballot regimes for each state. Orange indicates all-mail states, blue indicates states where an excuse is required to vote by mail, and pink indicates states where no excuse is required.

Ever since California instituted no-excuse absentee voting, twenty-eight states have taken the next step and allowed all residents to request an absentee ballot for every election. These permanent absentee states now have even greater use of absentee ballots. In 2022, the Survey of the Performance of American Elections (SPAE) reported that over 85% of voters in Washington, Oregon, Colorado, Hawaii, and Utah (all states with permanent absentee laws) voted with an absentee ballot.

The next wave in the expansion of voting by mail occurred during the 2020 election season, in which many states temporarily altered their absentee/mail ballot laws to grant greater access to mail balloting during the COVID-19 pandemic. The result was a significant increase in voting by mail for 2020, reflected clearly in the first figure above.

VBM: the Oregon system

In a referendum that passed in 1998, Oregon went a step further than California by agreeing to issue all its ballots by mail. Washington followed suit in 2011, and Colorado in 2013. More recently, these states were joined by Hawaii and Utah, which passed laws to begin voting by mail permanently with the 2020 election. While they have not made the complete switch to an all-vote-by-mail system, California, D.C., Nevada, New Jersey, and Vermont mailed ballots to all voters in 2020, as a COVID-related adaptation. (In the same year, Montana allowed counties to decide whether to mail ballots to all registered voters in their county.)

It's important to note that although Colorado, Oregon, Washington, Hawaii, and Utah now distribute all their ballots by mail, voters do not return them all by mail. According to responses to the 2022 SPAE, 21% of mail ballots were returned to some physical location such as a drop box or local election office. Thus, it's more accurate to describe these states as “distribute ballots by mail” states.

Administrative issues

The expanding opportunities to cast an absentee ballot or to vote by mail have not been uncontroversial. Perhaps the most important issues have been the question of whether expanding VBM opportunities increases voter turnout, and concerns over electoral integrity.

Facilitating VBM presumably reduces the costs of voting for most citizens, so one would expect it to increase turnout, yet the scientific literature on this empirical question about turnout has been mixed. An early study of the effects of VBM on turnout in Oregon argued that its implementation had caused turnout to increase by 10%. However, subsequent research has had difficulty replicating these initial findings. More recent research, using a variety of quasi-experimental methods, suggests the causal effect of VBM in these states in presidential election years is around 2 percentage points, although it may be as high as 8 points in Colorado.

The safest conclusion to draw is that extending VBM options increases turnout modestly in midterm and presidential elections but may increase turnout more in primaries, local elections, and special elections. This modest increase likely comes in two ways: by bringing marginal voters into the electorate and by retaining voters who might otherwise drop out of the electorate.

Another question surrounding VBM is whether it increases voter fraud. Two major features of VBM raise these concerns. First, the ballot is cast outside the public eye, and thus the opportunities for coercion and voter impersonation are greater. Second, the transmission path for VBM ballots is not as secure as traditional in-person ballots. These security concerns relate both to ballots being intercepted and ballots being requested without the voter’s permission.

As with all forms of voter fraud, documented instances of fraud related to VBM are rare. However, even many scholars who argue that fraud is generally rare agree that fraud with VBM voting seems to be more frequent than with in-person voting. Two of the best-known cases of voter fraud involving absentee voting occurred in 1997 in Georgia and Miami. More recently, a political campaign manager within North Carolina’s ninth Congressional district defrauded voters by collecting unfilled ballots and then filling in the rest of it to favor the campaign’s candidate, leading to a new election.

Finally, skeptics of convenience voting methods such as VBM argue that they encourage voters to cast their ballots before all the information from the campaign is revealed, thus putting early voters at a civic disadvantage. In response, as more voters cast early ballots by mail or in person, campaigns have less incentive to hold onto negative information about their opponents in the hope of gaining an advantage through an October surprise. Empirically, it's important to note that the earliest voters tend to be the strongest partisans and, thus less likely to be swayed by last-minute information.

Suggested Readings

Absher, Samuel, and Jennifer Kavanagh. 2023. The Impact of State Voting Processes in the 2020 Election: Estimating the Effects on Voter Turnout, Voting Method, and the Spread of COVID-19. RAND Corporation. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA112-25.html (August 1, 2023).

Altamirano, Jose, and Tova Wang. 2022. Ensuring All Votes Count: Reducing Rejected Ballots. Harvard University: Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation.

Atkeson, Lonna Rae et al. 2022. “Should I Vote-by-Mail or in Person? The Impact of COVID-19 Risk Factors and Partisanship on Vote Mode Decisions in the 2020 Presidential Election” ed. Noam Lupu. PLOS ONE 17(9): e0274357.

Cottrell, David, Michael C. Herron, and Daniel A. Smith. 2021. “Vote-by-Mail Ballot Rejection and Experience with Mail-in Voting.” American Politics Research: 1532673X211022626.

———. 2023. Election Administration and Voting Survey 2022 Comprehensive Report. https://www.eac.gov/sites/default/files/2023-06/2022_EAVS_Report_508c.pdf (July 6, 2023).

McDonald, Michael P, Juliana K Mucci, Enrijeta Shino, and Daniel A Smith. 2022. “Mail Voting and Voter Turnout.”

National Vote at Home Institute | Research Center

Ritter, Michael. 2023. “Assessing the Impact of the United States Postal System and Election Administration on Absentee and Mail Voting in the 2012 to 2020 U.S. Midterm and Presidential Elections.” Election Law Journal: Rules, Politics, and Policy 22(2): 166–84.